A hundred years ago, when Britannia still ruled the waves, the Royal Navy fell victim to a humiliating hoax, reports of which kept the public amused for a few wintry days in February 1910. Disguised as ‘members of the Abyssinian Royal family’, with woolly wigs, fancy-dress robes and burnt-cork complexions, a gaggle of young people managed to trick naval leaders into receiving them on an official visit aboard the state-of-the-art battleship Dreadnought, Britain’s proudest national emblem. The ridiculous party, which included Virginia Stephen (the future novelist Virginia Woolf), were conducted solemnly round the wonders of the newest naval technology, jabbering in a nonsense language and escaping just as the spirit-gum holding on their beards began to melt.

The prank’s mastermind was Horace de Vere Cole, the subject of this biography, who led the troupe, posing as a Foreign Office official. Once they were safely off the boat, the story quickly reached the press. The Navy was too embarrassed to retaliate, but William Fisher, the young Flag-Commander of the Dreadnought, who had been among those receiving the jokers — and was actually Virginia Stephen’s first cousin — felt the hurt acutely enough to attempt to horsewhip the (male) perpetrators. His efforts ended in absurdity, with Fisher and Cole laying about each other with canes.

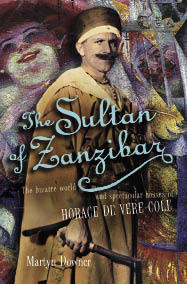

Cole was an experienced — and lifelong — hoaxer. Five years earlier, he had fooled the Mayor of Cambridge in a similar escapade — a state visit to the city by the ‘Sultan of Zanzibar’. The Dreadnought affair was later commemorated in a book by Virginia Stephen’s brother, Adrian, and has earned Cole a benign footnote in Bloomsbury histories as a kindly, if sometimes tedious, deflater of public pomposity. Perhaps it would have been best to leave his memory at that, for although this new biography by Martyn Downer presents a friendly and humorous portrait of an extraordinary personality, the tale it unravels is distressing, and Cole emerges as a bullying egoist, pathetically unable to cope with reality.

Large and impressive-looking, sporting mustachios of Kaiser Bill proportions, Cole undoubtedly had an élan vital and personal magnetism which gained him friends, or at least followers, in his pranks, but as he aged, these diminished. The heir to a considerable estate, he did nothing to preserve his wealth or to earn a living, and he became progressively more of an embarrassment and a bore. His incessant practical jokes (such as walking in front of trains, feigning epileptic fits, farting explosively in genteel surroundings) were interspersed with bibulous fights (his antagonists included Jack Yeats, and Jacob Epstein — who thrashed him) and with disastrous love affairs. Much of his louche existence he spent in London, where he was a habitué of such bohemian haunts as the Eiffel Tower restaurant and the Café Royal. He struck up a friendship with Augustus John, who became the paramour of Cole’s last great love, the passionate Mavis Wright (‘my Woffley Wooff’). Cole died aged 55 in 1936. His end, drunken and lonely in a French village, wretchedly married to the absentee Mavis, half his age and as much of a fantasist as himself, makes for depressing reading.

Likening Cole’s antics to those of Bertie Wooster, Martyn Downer describes him as stepping ‘fully formed and roaring, from the pages of P. G. Wodehouse’; from Saki would be nearer the truth. As a boy he is said to have used real poison for the murder scene in an amateur theatrical, nearly killing the leading lady. On another occasion he squeezed his stout German governess into a luggage lift and sent her hurtling groundwards from the nursery floor at the top of the house. He was happy to allow the spread of such tales to promote his reputation as a bold, ruthless trickster; but how much credence should be given to them it is hard to say.

In general, the evidence on which this book is based seems unevenly distributed. The early life and the Dreadnought episode are well documented, and the information well deployed; but Cole’s closing years get more than their share of attention, because the author has had access to a large cache of Mavis’s correspondence for that period. For the middle part of his life the records are patchier, and though Downer fills many pages with lively historical comment and anecdote one cannot help thinking that a more condensed narrative would have worked better — all the more so because this book has so many good and pithy things in it, not least, Augustus John’s feelings as he watched Cole’s coffin being lowered into the ground:

In dreadful tension I waited for the moment for the lid to be lifted and a well-known figure to leap out with an ear-splitting yell. But my old friend disappointed me this time.

Comments