When Tom Tugendhat announced he was backing Liz Truss for prime minister, his former supporters were dismayed. He was the candidate for the ‘One Nation’ caucus of moderate MPs, who defined themselves against the Tory right. ‘Anyone but Truss’ was their mantra – and they lined up behind Rishi Sunak. Yet here was their former poster boy supporting their nemesis. What could Truss and Tugendhat possibly have in common? The answer can be summed up in a word: China.

For better or worse, Truss is an instinctive politician. On foreign affairs, she was held back by Boris Johnson, who was more cautious on China. If she becomes prime minister, which looks likely, she would spend more on defence and take a more muscular stance against aggressors. It’s a pitch that’s already won over Defence Secretary Ben Wallace; Penny Mordaunt, his predecessor; and Trade Secretary Anne-Marie Trevelyan.

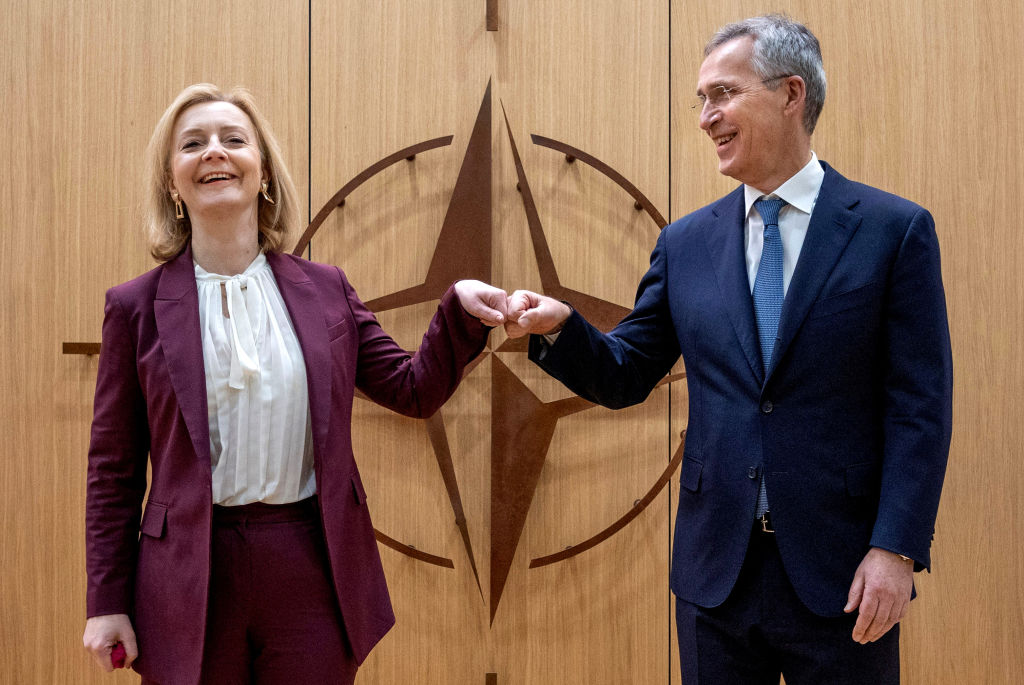

As the public imagines what life would be like under a Prime Minister Truss, it’s on foreign affairs that we have the clearest idea. Since entering the Foreign Office in September she has earned a reputation for her love of Instagram, her dislike of groupthink and her diplomacy via karaoke. But most importantly, she has established her own framework on foreign affairs, which she refers to as the ‘network of liberty’. She divides the world into friends – and enemies -– of liberty.

Rather than focusing on relations with western neighbours or long-established allies, she thinks the UK should be open to working with like-minded, free-trading partners around the world who are willing to prioritise the defence of democracy. ‘Call it geo-liberalism,’ says a supporter.

Those close to Truss envisage her taking a bigger role on the world stage and an active interest in trade. The UN General Assembly in New York would likely be her first trip; it’s scheduled a week after the new prime minister takes office. Visiting Kyiv would also be a priority and her first foreign call would go to President Volodymyr Zelensky, assuring him that Britain is every bit as committed to Ukraine as it was under Johnson.

When Emmanuel Macron recently proposed a new European ‘political community’ in the face of the Ukraine crisis, Johnson gave the idea some lip-service. But it’s unlikely to receive the same from Truss. She didn’t mention the EU once in her first party conference speech as foreign secretary and made her first official visit to France only last month. At the Tory hustings this week, she declared that the only thing the EU understood was ‘strength’, which was why she had introduced the Protocol bill (which some MPs fret will lead to a trade war).

She believes the UN is fatally compromised by having China and Russia as two of the five permanent members of the Security Council. She would instead look to the G7 as the means for defending democracy. She is enthusiastic about Nato and the Commonwealth and has long fought for the UK to be a member of the transpacific trade partnership, viewing economic policy as a way to strengthen alliances.

Although her stance on Ukraine would not see much divergence from Johnson’s, it could be more hawkish. She has been one of the most vocal advocates for sending defensive weaponry to Ukraine and the need to keep up resolve. Like Zelensky, she abhors suggestions of Ukraine cutting any peace deal – believing that it would only lead to Vladimir Putin rearming and returning. ‘She thinks another Minsk deal should be avoided at all costs,’ says one aide, referring to the Franco-German pact which in effect accepted Russia’s annexation of Ukraine.

In this regard, she is a Ukrainian maximalist. In her Mansion House speech in April, she said Russia must be pushed out of ‘the whole of Ukraine’ – suggesting this should include Crimea, which Russia annexed prior to the February invasion. This was decried by her critics as a dangerous escalation. But her position is in line with Ukrainian public opinion.

A Truss government would be likely to take the toughest position on China of any to date

The last book she read was Winter is Coming by Garry Kasparov, the exiled Russian grandmaster who wants world leaders to ‘throw Russia back into the stone age’. Truss believes the West has a tendency not to listen to voices from Russia and the neighbouring states. She’s built close ties in the Baltics, including with her Lithuanian counterpart Gabrielius Landsbergis. When his government let Taiwan open a trade office in Vilnius under its own name, the CCP was so enraged that it stopped imports from Lithuania.

A Truss government would be likely to take the toughest position on China of any to date. In any G7 discussion about China, she would be expected to be among the most hawkish in the room. She previously suggested that western countries needed to ‘learn the lesson’ of Ukraine by arming Taiwan early to prevent a Chinese invasion – though her campaign suggests she would prioritise ‘moral support’. She would also take a firm stance on trade with China – and is more open than her predecessor to the so-called genocide amendment which could give British judges the power to annul trade deals with countries convicted of genocide.

As trade secretary, she wanted to go further than No. 10 would allow on free trade with allies – and saw herself as fighting what her aides jokingly called a protectionist ‘axis of evil’, which included Michael Gove and George Eustice. This was despite the fact she represents a farming constituency, where there could be opposition to her position.

Under PM Truss, freedom-loving allies – from the Indo-Pacific to the Baltics – would be welcomed into the fold. But there is also space for those who don’t yet fit the bill. Truss thinks it is better to keep the likes of Indonesia and Saudi Arabia on side, rather than allowing them to be wooed by aggressors such as China and Russia.

In a Truss era, liberty (which also happens to be her daughter’s name) will be the defining principle, not just when it comes to tackling the nanny state but on the world stage too. Her approach will create plenty of challenges for Britain – but it’s a risk the Tory party looks as though it wants to take.

Comments