Today marks two years since Boris Johnson accepted Her Majesty’s invitation to serve as her fourteenth Prime Minister. His tenure was meant to be all about Brexit but so far has mostly been about Covid, yet the invisible theme running under it all is the constitution. Britain is almost a quarter-century on from the legislative devolution experiments in Scotland, Wales and London, which leeched power away from Parliament and created rival seats of political authority to Westminster. Scotland is where devolution has taken its most aggressive form and where it has done the most to undermine the Union, parliamentary sovereignty and even the continued existence of the United Kingdom itself.

Two years in, the Boris era has brought modest relief from the policy of ever-weaker Union. The government has embraced direct investment in Scotland, as some of us argued for it to do, and aims to reassert Westminster’s authority in limited but important ways through the Internal Market Bill. For a Prime Minister with the biggest Tory majority since Margaret Thatcher, however, this is an underwhelming output. Meanwhile, the separatists are on the march. The SNP government in Edinburgh incorporated the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child into Scots law, thus creating legal obligations on the UK gDovernment, which has chosen (under Labour and Tory administrations) not to place the convention on a statutory footing. Whitehall only belatedly grasped the implications of Nicola Sturgeon’s actions and the matter is now before the courts.

It is possible to forgive the Prime Minister for being neglectful or cowardly, but another potentiality is harder to excuse: that he lacks the ambition or vision

This is of a piece with Sturgeon openly pursuing her own foreign policy, even though foreign affairs is reserved to Westminster, and exploiting the institutions of devolution to bring about Scottish independence, even though the country was assured that creating the former would vanquish the threat of the latter. Sturgeon’s government says it intends to go ahead with another referendum on breaking up the UK — a proposition that only people living in Scotland would be allowed to vote on — even though the authority to hold such plebiscites is supposed to lie with Parliament. I have argued that Parliament must urgently legislate a new Act of Union, putting beyond all doubt where sovereignty resides, the limits of Holyrood’s powers and explicitly prohibiting the Scottish government or parliament from committing public resources to non-devolved matters. Others have made a similar case.

It was always a long shot that Boris Johnson would use his majority to reform devolution, secure the Union and move the country on from constitutional inertia, but, as I argued elsewhere, his appointment of Scottish Tory party director (and Ruth Davidson ally) Lord McInnes as his special adviser on Scotland suggests the Prime Minister is not minded to grasp the thistle. It’s hard to blame him, of course, given what little thanks he would get for it anyway, not least from the weak-kneed devo-fearties in his Scottish party. Yet, for a prime minister who personally considers devolution a ‘disaster’, and who is said to harbour a desire to ‘reverse’ the policy, the case for reform should be getting more consideration than it is.

Perhaps Scotland and broader constitutional dilemmas are too far down his list of priorities and would remain there even after the pandemic. Perhaps he fears the backlash a reform agenda would provoke in Scotland and frets that some in his own party might even join it. It is possible to forgive the Prime Minister for being neglectful or cowardly, but another potentiality is harder to excuse: that he lacks the ambition or vision. Not wanting go down in history as the Prime Minister who lost Scotland, Boris may have determined he can do that without burning up political capital on an agenda that could prompt as much bewilderment in England as it would animosity in Scotland. That is, he may simply have opted for a quiet life on constitutional affairs.

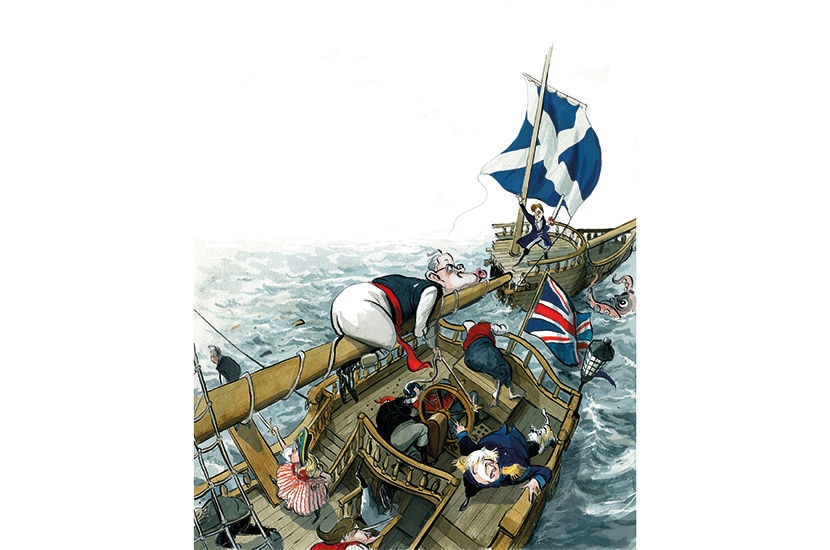

Seeing off the immediate threat of separatism and making measured changes to the devolution settlement would cause consternation but nothing that a government with a bit of backbone couldn’t weather. It would also provide a fitting legacy for a man who gave himself the title, ‘Minister for the Union’. After two years, however, Boris’s contribution to the constitutional question is a little bit of progress and a whole lot of drift.

Comments