‘Can you read Dickens’s handwriting?’ asked a blogger. Underneath was a picture of his manuscript for chapter 23 of Oliver Twist. It looked easy enough to read: ‘If the village had been beautiful at first it was now in the full slow and luxuriance of its richness.’

No, slow couldn’t be right. Must be flow. But no. The published text tells me it is ‘full glow and luxuriance’. I should have seen it the first time, for even in one paragraph of Dickens’s writing, it is obvious that he made his gs like a descending s or a barless f. When a g was joined to the preceding letter, he would carry the stroke up and into a tight anticlockwise loop, then plunge down to make the tail. Forming letters is a thing we do half-consciously, and consistency of habit makes our handwriting recognisable, or it did when we all wrote every day.

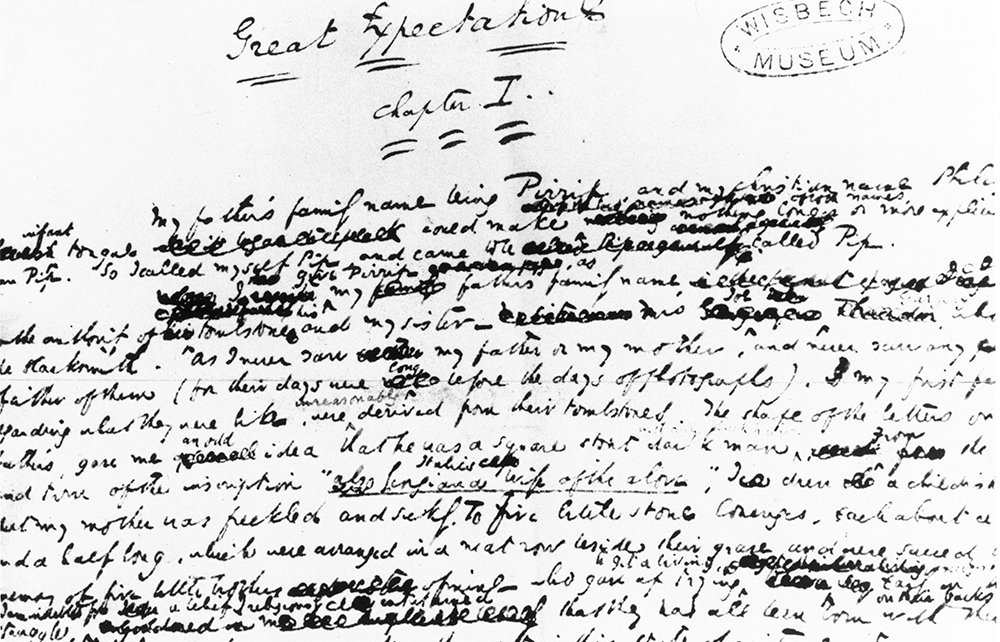

The Hunts Post, in an article about the manuscript of Great Expectations, which is in Wisbech museum, claimed that Dickens’s handwriting was ‘spidery’ and at the end of that manuscript ‘virtually illegible’. An article in the Guardian last year said that was a ‘notoriously messy writer. His manuscripts are full of inky splodges, with barely legible alterations crammed in between scrawled, sloping lines’.

But these were the manuscripts from which the compositors set his novels in type, and they seem to have done a pretty good job. All newspapers and books were handwritten in his time, and printers grew accustomed to a writer’s foibles. Even after typewriters came in, corrections, sometimes with pages full of new matter, were by hand. In the 1980s I sometimes delivered copy for this column in manuscript.

Dickens wrote no more neatly in letters to friends. Writing to Mark Lemon in 1849, he says that a play ‘went admirably – rose as it went on…’. On the paper manuscript, someone has written in pencil ‘rose’ above Dickens’s word, to make it plain. But I wonder if future generations will be able to read the amendment any more easily.

Comments