There are certain things that you don’t expect at the opera. Laughter, for example. Proper laughter, that is; not the knowing sort that ripples politely across the auditorium five seconds after the punchline appears in the surtitles. We’re talking unconstrained laughter; laughter that gives you an endorphin rush and sends you straight online to tell your friends that they must see the show.

But that’s Cal McCrystal’s whole business. He’s the director who devised James Corden’s delirious plate-spinning capers in the National Theatre’s One Man, Two Guvnors and whose face (in motion-capture) provided the elastic expressions of a small Peruvian bear in Paddington.

‘I want every production I do to be the funniest I’ve ever done. I’m instinctive when I direct’

McCrystal is the king of the sight-gag and the pratfall: a virtuoso creator of physical comedy whose credits range from Cirque du Soleil to The Mighty Boosh and whose sudden, glorious swerve into comic opera over the past few years hasn’t so much blown fresh air through the genre as, well, smashed onstage and seen him start hurling things about. And now, somehow, he’s at Glyndebourne, and about to open a new production of Lehar’s The Merry Widow. How on earth did that happen?

‘When I was at the National Theatre, someone said, “Have you ever thought of doing opera?”’ says McCrystal. ‘I went, “Good heavens, no. Who’s going to give me an opera?” In 2014, English Touring Opera gave me Haydn’s Il mondo della luna, and it did very well, and people absolutely loved it. But when English National Opera offered me a Gilbert and Sullivan, I don’t think they even knew that I’d done an opera before.’

Soon everyone knew it: McCrystal’s 2018 staging of Iolanthe might have been the most gleeful, game-changing take on Gilbert and Sullivan since Jonathan Miller gave The Mikado an art deco makeover in 1987. ‘I think my operatic career really did start with Iolanthe, because that was a massive success for ENO,’ he says. ‘My conductor at that time said to me, “Of course, you realise the traditionalists are going to hate this.” And I said: “No, they’re not. I’m making a show that everyone will love.” They were selling standing room in that big theatre.’

That led to HMS Pinafore at the Coliseum and Rossini’s bawdy Le Comte Ory at Garsington. And now to Glyndebourne, which possibly doesn’t realise what’s about to hit it. The Merry Widow was a global sensation back in 1906, and it’s something of a departure for the Sussex festival, which has traditionally considered itself a bit too grand for mere operetta. Until, that is, Covid struck and an improvised staging of Offenbach’s cross-dressing farce Mesdames de la Halle became the smash hit of a devastated season.

‘That’s true – and it’s true across the board,’ says McCrystal. ‘After the pandemic, everyone has become desperate for the collective experience, and there’s no collective experience better than laughing along. Comedy is a conversation between the audience and the company: it’s back and forth all the way. It’s true in conventional theatre as well. In the West End they’re now having to throw people out for singing along – whereas in this production we’re actually encouraging people to hum along with the waltz.’

Humming along at Glyndebourne? That should be interesting. For McCrystal, it’s all about connecting with the whole audience – a lesson that the opera world too often forgets. Cynics might suspect that if McCrystal had, say, drained all the joy out of The Marriage of Figaro rather than filled London’s largest theatre with roaring capacity crowds, he’d be winning industry awards by now.

What’s clear is that McCrystal takes the craft of physical comedy very seriously indeed. He trained in Paris under the famously severe (a very French paradox) master-clown Philippe Gaulier. Nicholas Hytner, the director of One Man, Two Guvnors, noted that in rehearsal, McCrystal ‘rarely breaks into anything warmer than a wintry smile’. All that energy and comic inspiration is channelled towards the performers – and through them, to the audience.

‘I want every production I do to be the funniest I’ve ever done,’ he says. ‘I’m very instinctive when I direct. I like cultural references but when I go into a rehearsal room, I basically think, “Right, what are we going to do with this?” And then I try to gather everyone’s sense of humour together and make something that’s fun and affecting.’

The results have been life-enhancing: never a given when opera aims for laughs. McCrystal has encountered some unexpected challenges along the way.

‘It’s extraordinary. The opera world has been going for such a long time and they still don’t know how a show is made. During the dress rehearsals building up to opening night – when in theatre you’d be working till midnight, and getting it right – they don’t do anything like that. Because of union rules, we’re working five-and-a-half hours a day. There’s no time to give notes after dress rehearsals, so I’m having to run around dressing rooms trying to catch people before they leave. Here I am down in the middle of the countryside and I’m only able to work five hours a day.’

And then there are the problems endemic to the British operatic ecosystem, where fear of offending an opera-hating Arts Council can reduce even a major national company to a state of timorous compliance.

‘I think there was a neurosis at ENO,’ says McCrystal. ‘I mean, in Pinafore I had Boris Johnson falling into the sea, and Annilese Miskimmon [ENO’s artistic director] begged me not to do it. I said, “No, I’m not cutting it, I’m sorry.” And in fact, at that bit, John Major, who was in the audience one night, stood up and clapped. He stood up in his seat and clapped! You have to keep all those naughty bits in!’

In that regard, at least, Glyndebourne is a more congenial working environment. ‘I think one of the differences is that Glyndebourne is not a public-funded company. The management here are incredibly relaxed and supportive of each director coming in – helping them to realise their own vision.’

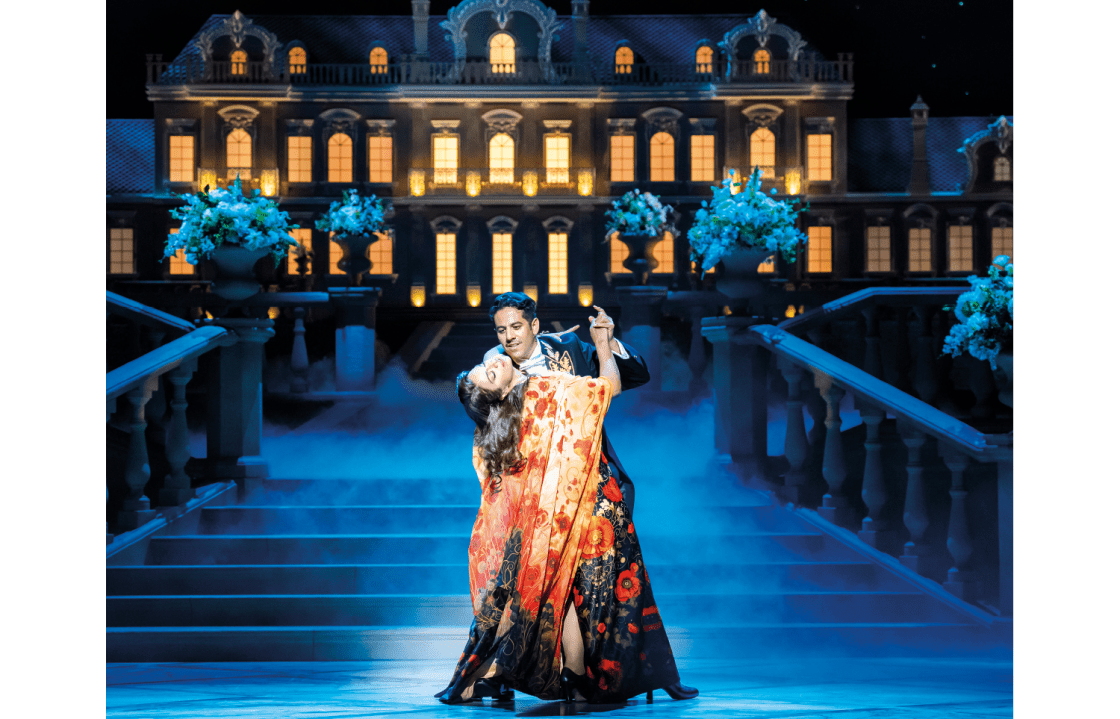

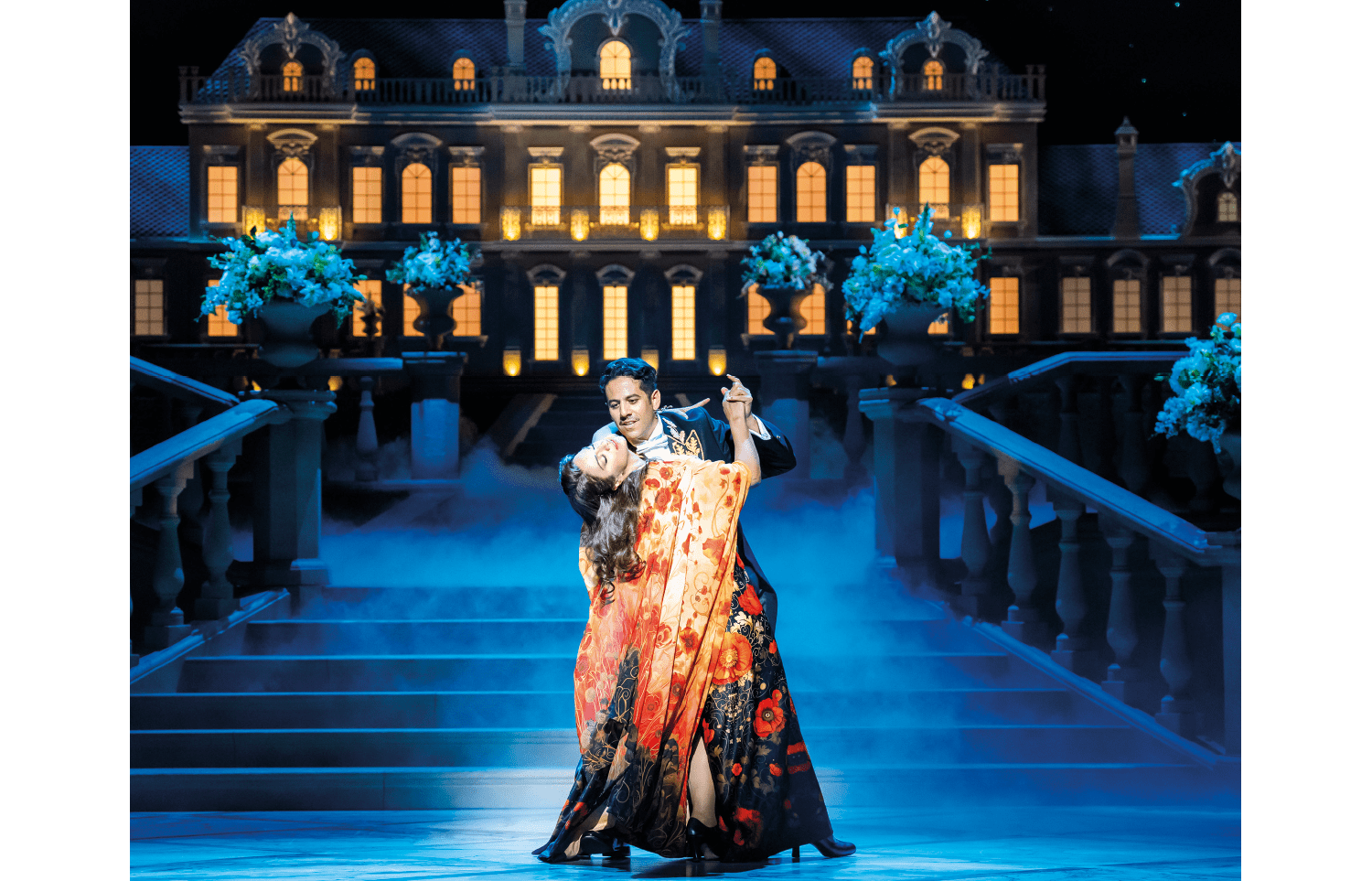

And The Merry Widow, famously, is a different sort of comic opera: funny, for sure, but with a heart as warm as Lehar’s sensuous, seductive melodies. It’s possible that we’re about to see a more romantic side of McCrystal. ‘My initial instruction to the designer was to make a Hollywood musical,’ he says. ‘It really does look full-on MGM.’ Yet the music – crucially – remains the core of the show.

‘It’s very joyful, all the things that Lehar has given us – all the opportunities he’s given me to have fun with these characters, and to play in an arena where everyone knows all the tunes. Everyone holds these songs in their heart: my grandmother hummed them to me when I was a child. What I’m doing now, I hope, is what I tried to do with Iolanthe and HMS Pinafore: to give it a bit of a refresh. With an element of lampoon, but not humiliating the piece itself – because you acknowledge that the piece is already good.’

That’s true enough. With John Wilson conducting a cast that includes Sir Thomas Allen, as well as the extrovert soprano Danielle de Niese in the title role, there should be something in this Widow to set even the most fastidious of opera buffs purring. But McCrystal, as ever, is aiming higher.

‘I’ve been a pig in muck doing this, I really have,’ he says. ‘I mean, every single day I spring out of bed – I can’t wait to get into rehearsal. I feel very lucky to be doing opera. Even though I do theatre and circus, and shows in Las Vegas, and all the rest of it, the comedy is the binding thing. My career is a bit less random than it seems. I apply the same objective to everything I do – which is to make the people who are there laugh.’

The Merry Widow is at Glyndebourne until 28 July.

Comments