It’s rare nowadays to see a new opera production that’s set in the period that the composer and librettist intended, but they do occasionally come along. In the case of Leonard Bernstein’s operas Trouble in Tahiti and A Quiet Place, the time and place are basically the whole plot. Trouble in Tahiti dates from 1951; a sassy little one-act satire on America’s postwar consumer idyll. It’s practically perfect. A Quiet Place is from 1983 and it’s a sequel, set 40 years later – post-Vietnam and post-Woodstock, with the nuclear family in full meltdown.

These performances, and this production, provoke thoughts that might rob you of sleep

It’s a bit of a mess, in other words, and Bernstein never really made the pairing work. His final version stuffed the whole of Trouble in Tahiti inside Act 2 of A Quiet Place: an operatic turducken, scored for a hefty orchestra (complete with synthesiser – this was the 1980s, after all) and duly ignored by all but the most dutiful American companies. The Royal Opera restores Tahiti to its pristine form, and puts A Quiet Place on a brutal weight-loss programme, trimmed and tucked into coherence by Garth Sunderland. Both are rescored for a chamber ensemble. Bernstein never heard or authorised this version, though given what he did authorise in his later years we probably shouldn’t worry too much about that.

Trouble in Tahiti is always fun, and Oliver Mears handles it with wit, using the Linbury’s letter-box stage to create a suitably 1950s split-screen effect as the young married couple Sam (Henry Neill) and Dinah (Wallis Giunta) go about their suburban lives. Giunta is terrific; an all-dancing knockout, just as she was when she sang this role for Opera North in 2017. Mindful that the piece is now essentially a prologue, Mears goes easy on the satire and starts to pick at the vulnerabilities of both characters. Dinah is hitting the bottle, and as Sam, Neill lets a defensive, pained edge enter his voice when he works out at a (distinctly homoerotic) gym.

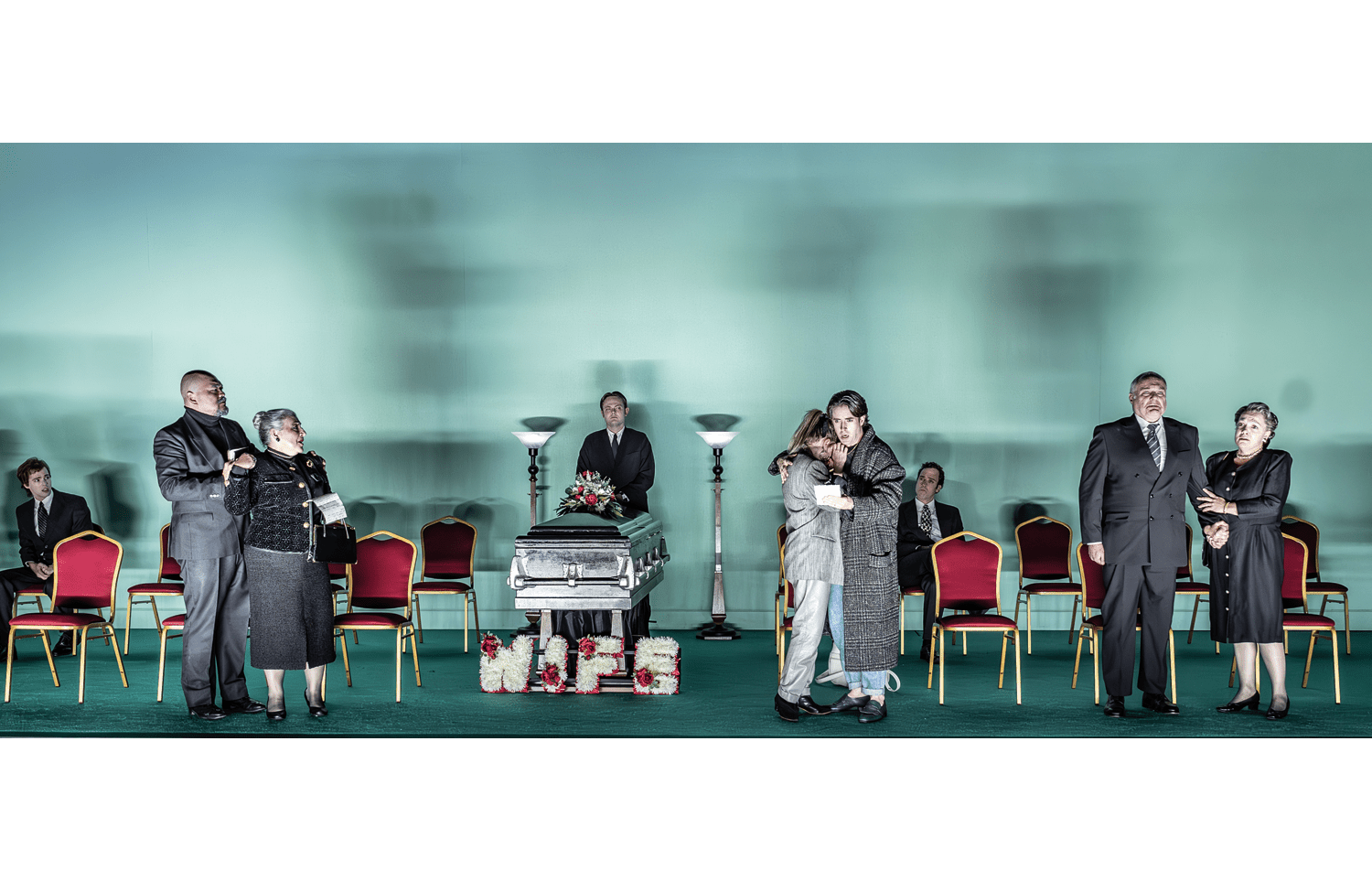

This is intelligent directing, and it pays off in A Quiet Place, which opens at Dinah’s funeral with the couple’s estranged adult children centre-stage. The early-1980s signifiers are amusingly etched, with big hair, rolled-up jeans and daughter Dede (Rowan Pierce) looking kooky and kohl-eyed in an oversize trouser suit – very Annie Hall. Their son Junior (Neill again, utterly transformed as the moustachioed, shorts-wearing gay stereotype of red-state nightmares) is a mentally ill draft-dodger, and the siblings’ (apparently) shared lover François (Elgan Llyr Thomas) is from Quebec. An elderly, embittered Sam is now sung by Grant Doyle, in a performance that flips from steely aggression to sudden, fragile tenderness, sometimes within the same bar.

Still, ‘What a fucked-up family!’ exclaims one character. Mears does his best to dig beneath the wisecracks and point-making, and if Bernstein’s late lunge for redemption doesn’t quite ring true, the fever-dream mood swings of a family forced together by grief are superbly drawn, with Pierce in particular finding pain and anxious laughter in that lovely, lucid voice. It’s a fidgety score and the conductor Nicholas Chalmers keeps a cool head. Even so (and even in the reduced scoring) the orchestra occasionally overwhelmed the voices. That’ll probably come out in the wash; meanwhile you’re unlikely to see a better case made for A Quiet Place. This is a bold, thoughtful staging of an opera that tries hard – possibly too hard – to do something different.

There’s equally sophisticated theatre over at English National Opera, where Isabella Bywater’s staging of The Turn of the Screw is the company’s first really substantial new production in nearly 18 months. The setting (Bywater is the designer, too) is a psychiatric hospital about 50 years ago (to judge from the nurses’ uniforms) – which, since the action is portrayed as the memories of the now-ageing Governess (Ailish Tynan) places it within striking distance of Henry James’s era. The drab institutional walls slide back and forth, while black and white film of a country house flickers and whirrs to disorienting effect.

Apparently Hitchcock was an inspiration and that’s certainly the effect here: psychological thriller rather than ghost story, with Britten’s music taking on a Bernard Herrmann-like weight and tension under the baton of Duncan Ward. You’d never guess that there were only 13 players. The two children (Jerry Louth and Victoria Nekhaenko on the first night) were unnervingly self-possessed, and Robert Murray, as Peter Quint, suggested menace with controlled gestures and a voice that took on a cold, hollowed-out ferocity. Tynan’s singing, meanwhile, told its own tale as she pottered about in her slippers; sweetness, anxiety and a haunted, fading sadness at the ends of phrases. A memory of despair, or a dread that’s still present and active? These performances, and this production, provoke thoughts that might rob you of sleep. That’s a recommendation, by the way.

Comments