Living and working as a dairy farmer in Shropshire, I’ve witnessed firsthand the fallout from Rachel Reeves’ recent Budget. It has dealt a catastrophic blow to the farming industry, leaving many of us reeling.

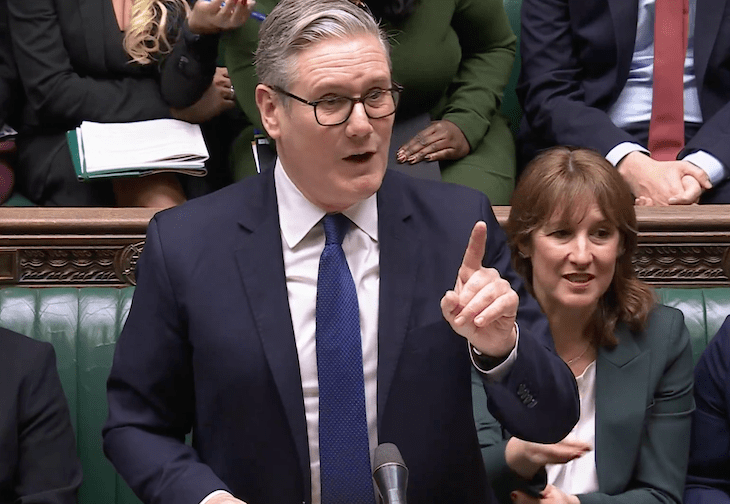

Just a year ago, the now Environment Minister Steve Reed promised us there would be no changes to agricultural property relief (APR). Now Labour has taken a bulldozer and smashed the policy to smithereens without any consultation with Defra (the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs) or the farming community, leaving us scrambling to process the changes and adapt.

The charges Labour have brought in will reshape British farming and our country’s landscape

I come from a family which has farmed in Shropshire for generations and my husband, whom I married in 2007, is himself a sixth-generation dairy farmer. When we met, his dairy unit was an all-year-round calving system, fully housed in winter and grazing in summer. The business was £500,000 in debt, skilled labour was difficult to find and to continue the business, capital investment of £600,000 was required.

In 2010, we had to take a further capital investment of £600,000 to change dairy farming systems and become financially sustainable. The money was spent on changing to a cross-bred herd, installing a new milking parlour, improving farm tracks and water troughs, and purchasing calf heifers – our cows produce high-quality milk (high in fat and protein to make butter and cheese). In 2021, we bought a second farm in Staffordshire for £1.6 million. These continued investments, funded largely through loans, were necessary for us to sustain our business.

But the new APR rules threaten everything. Our original family farm, minus debts, would be subject to additional inheritance tax duties of £590,000. The farmhouse would incur tax of £160,000. A further payment of £90,000 would be payable on buildings, machines and livestock.

The inheritance liability is £840,000, for which HMRC offers a ten-year repayment plan, but this would still place unbearable strain on our cashflow, already stretched by existing debt. Farming is risky and this tax raid would make business unsustainable.

The farming way of life was already under immense stress even before Reeves’ Budget. Brexit ended EU farming subsidies and opened the door to cheaper, lower standard food imports that undercut UK farmers. The Conservative government began phasing out their farming subsidies, and Labour’s budget has hastened their demise.

Sustainable farming incentive (SFI) grants were introduced to replace subsidies, but the process is burdensome and costly. Like many other farmers, we resorted to hiring a consultant to navigate the red tape. Often only the landlords of larger farms can afford this – smaller farmers, faced with the expense and bureaucracy, may simply not bother, and they suffer most.

Most of us are feeling pressure from all sides to improve our climate emissions, biodiversity and sustainability. We were evaluating which environmental projects we could afford, and which might improve a farm’s efficiency, but these projects will now have to be put on hold. We’re servicing debt and with higher interest rates, economic volatility and new government policy we need to ensure we can meet our financial responsibilities first.

This year, we wanted to financially consolidate our farms for several reasons: the possible change of government, UK debt levels (unsustainable), fluctuation in global dairy commodity prices, the high level of farm production costs (thanks to the impact from the war in Ukraine on fuel and fertiliser) and low milk prices. That said, we haven’t escaped investment entirely – we will be able to plough a further £40,000 into new machinery and improving our land drainage system.

The National Farmers Union (NFU) reports that 75 per cent of commercial farms exceed the £1 million APR threshold, making them liable for significant taxes. Labour, though, claims only a small proportion of farms will be affected, but this is misleading. The new inheritance tax, pegged at 20 per cent, will leave many working farmers with an unmanageable bill that will force them to sell their land and assets.

There’s the mistaken belief that farming is a wealthy profession. While we may be asset rich, much of this wealth is underpinned by loans and the cash flow is always tight. In fact, returns on investment are small in comparison to other industries at about 0.5 per cent, and profits are needed to be channelled into essential repairs and replacements. As for income, figures published by Defra show that the average last year was just £45,300 per farm.

There’s the mistaken belief that farming is a wealthy profession

It has been suggested by Labour that farms are simply divided out between farmer, spouse and children to maximise tax relief. But this, again, isn’t so simple. It’s a tradition with farmers that they themselves should be the custodian of the farm, that it’s their duty to conserve it and pass it on when they die. Dividing it up with a spouse or children who haven’t yet decided whether to continue in the profession could be disastrous to the farm’s future. In our own case, we will have to restructure the business and consider splitting farm ownership. Our sons are aged 16 and 13; it’s too early to know yet if they want to farm.

The charges Labour have brought in will bring dramatic changes to all and reshape British farming and the landscape. Our whole way of life, going back millennia, will be damaged and our culture and landscape altered forever. Family farms could eventually be amalgamated into much bigger units, and land repurposed for environmental schemes, with large multinationals hoovering up hectares for carbon capture, and to offset emissions. Dairy operations risk shifting to intensive farming models, with 1,000-plus cow herds confined indoors to sheds. Beef, pork, fruit and vegetables will increasingly be imported. Buying local, sustainable food will become an expensive luxury and food security – a critical issue in a volatile world – will be under threat.

For consumers, the impact will be felt in rising food costs and a threat to our food security. Plant-based products touted as sustainable offer low nutritional content per calorie, and, as they come to dominate supermarket shelves, obesity rates could climb. Meanwhile, the UK landscape of grazing livestock will vanish, replaced by solar panels and wind farms, by housing or intensive farming on an industrial scale.

Another knock-on impact will be on farmers’ mental health. The farming profession already has the highest suicide rate in Britain, and with this additional tax burden, this will only get worse.

Beef, pork, fruit and vegetables will increasingly be imported

The unluckiest ones, those I really feel empathy for, are those aged between 50 and 60, whose fathers (over 80) haven’t passed on the farmland. Older farmers feeling they’ve failed to secure their children’s futures are deeply distressed. One arable farmer we are very good friends with is in his mid-fifties. In partnership with his 82-year-old father, he’s steadily built up his business, buying more acres and spending £100,000 plus on each machine. His dad still owns the farm and has been emotionally broken by what’s to come, feeling he hasn’t sufficiently protected his sons’ farming future. At the same time the country is talking about euthanasia, older farmers are talking about when best to die.

Labour’s new tax rules feel like a betrayal. The government could have opted to exempt farmers over 80, introduced a phased roll-out or increased the tax threshold. Instead, they’ve alienated the very people who put food on the nation’s tables.

This isn’t just about protecting farmers. It’s about safeguarding a way of life, ensuring food security and preserving the environment. Farmers are custodians of the land, working tirelessly to conserve it for future generations. It’s imperative for policymakers to listen, engage and develop solutions that recognise the vital role farming plays in the UK economy and culture.

The stakes couldn’t be higher. The choices we make today will determine not just the future of British farming, but the health, security and identity of our nation.

Comments