I had been kicking my heels in a dusty two-star hotel on a dual carriageway in Leon, central Mexico, for days. One afternoon, I spotted a battered old English language hardback in a junk shop window: Under the Volcano by Malcolm Lowry.

I had read the book before, half a lifetime ago, in maybe 1985, when I knew nothing about Mexico, failed relationships or alcoholism. Almost 40 years later, with a more than working knowledge of all three, I felt better placed to appreciate Lowry’s 1947 masterpiece. With nothing else to do or read, I bought it. I haggled the shopkeeper down to 100 pesos – about £4.

Barely 24 intense hours later – the same time span that the novel unfolds in – I had finished it. Or had it finished me? Certainly the experience of reading it seemed to wipe me out emotionally.

It’s set in a single day but it took Lowry eight or nine years to write Under the Volcano. It never would have been released without the help of his second wife, Margerie Bonner, who edited it into publishable shape. It describes a love triangle involving alcoholic British consul Geoffrey Firmin, his estranged actress wife Yvonne and his failed-musician-turned-cowboy half-brother, who’s just back from fighting in the Spanish Civil War.

The story plays out in the Mexican town of Quauhnahuac – a fictionalised rendering of Cuernavaca. The day begins with the consul – the Lowry character – drinking whisky at 7 a.m. Things only get messier as the day progresses. It’s a chaotic and intense book – and very, very sad. Coming to it a second time, I found it hauntingly well done.

I was in Mexico because I was meant to be shooting a film in Guanajuato for an American journalist who’d paid for me to fly out. But a series of mishaps had turned a short wait into a long one. So the return to Lowry was the most exciting thing that had happened to me in three weeks. With still no shooting schedule in sight, and the book burning in my mind, I started Googling and found that the book’s real-life setting was only about 300 miles away – south-east of me, close to Mexico City.

Four hours later I was on a night bus, alone, exiting the mountain basin of Leon, and six hours after that, a huge cement factory heralded the notorious sprawl of the Mexican capital where I changed buses at the Terminal del Sur. After another 60 miles, I was coming into Cuernavaca.

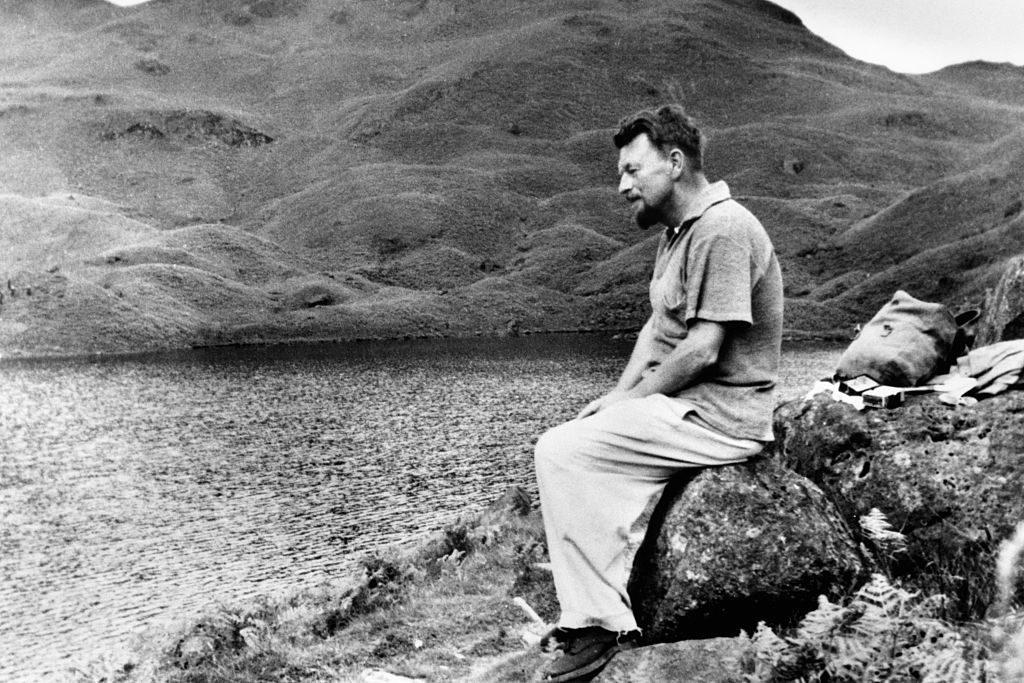

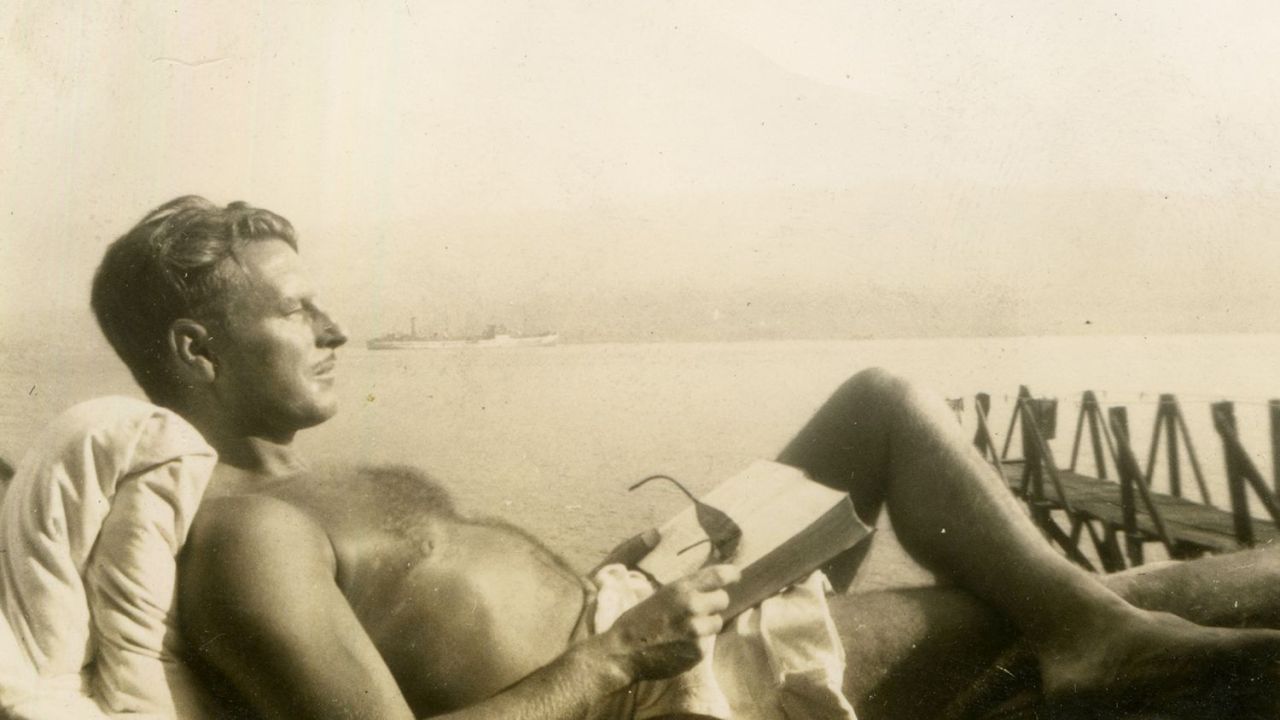

Lowry had arrived in Cuernavaca with his first wife Jan Gabrial on 2 November 1936, the Day of the Dead – the day he would set the novel in. She had already run away from him once, moving from Paris to New York in April 1934, but he had followed her. And she took him back, staying with him for another two years, despite him admitting himself to Bellevue Psychiatric Hospital with an alcohol-induced breakdown.

With the book burning in my mind, I started Googling and found that its real-life setting was only about 300 miles away. Four hours later I was on a night bus, alone

They had moved to Mexico to try for a fresh start. But in Cuernavaca, she finally left him for another man. In her memoir Inside the Volcano, Gabrial later suggested that a lot of Lowry’s problems had to do with his ‘tiny penis’.

Popocatépetl volcano, which gave Lowry his title, is 50 miles east of Cuernavaca. At 18,500ft it is Mexico’s second highest peak – although I still managed to miss it, despite straining for a view as my bus finally rolled into town. But as we drove through the sprawling outskirts, I saw something that took me back to the book: two soldiers on horseback, riding through a pine forest. This echoed the processions of soldiers mentioned in the novel’s memorable ending. No spoilers, but it doesn’t end happily.

Cuernavaca has always been a retreat for elite chilangos – wealthy natives of Mexico City – but the bus station barrio was reassuringly down-at-heel. Five minutes after stepping off the bus I hit my first Lowry landmark: the latticed pink-and-white plaster facade of Teatro Morelos, a cinema, where the consul’s friend Laurelle finds his desperate letter to Yvonne hidden in an anthology of Elizabethan plays. As he burns the letter, a bell tolls twice – the city’s fortified cathedral is next door.

The Teatro Morelos was absolutely as I imagined it, and although the interior had been gutted, it was still a cinema, which seemed remarkable. Outside, a woman in rags, berating the traffic, put me in mind of the woman playing dominoes with a chicken in Chapter 8. Across the street, a fat man busked for small change on his tuba.

Feeling pleased with my first encounters, I took breakfast in the corner cafe before walking 20 minutes to my lodgings at the Hotel Bajo el Volcán, which is built around Lowry’s actual house. The original Art Deco tower is still there, but the front of the building has been replaced with a pretty bad stone facade which takes you into reception. The guest rooms are just little cabins built in the grounds behind. Outside my cabin, huge black beetles were drowning in a small swimming pool. I rescued a few.

In the afternoon I went looking for what interested me most: The Hotel Casino de la Selva where Jacques Laurelle and Dr Vigil drink anisette in the opening chapter of the book. The streets were blighted by high-walled chilango ‘castles’ – the Mexican equivalent of what we might call footballers’ mansions’ – bordered by shops and street-food traders.

Unfortunately, the once magnificent Casino de la Selva had disappeared. In its place stood two huge chain supermarkets skirted with hundreds of grey parking spaces. The only trace of the Latin Gatsby’s playground was the brutalist ‘hyperbolic paraboloid’ shell of architect Felix Candela’s dining room, which still served food under the management of Casa de los Abuelos – literally ‘grandparents’ house’. Avenues of old trees hinted at former glories, but you felt the steel and concrete supermarkets were in the ascendancy.

Such indifference to history shouldn’t come as a surprise. Mexico’s natural heritage currently faces a potentially catastrophic threat from an ugly railway which is ploughing through the last tracts of virgin jungle in the states of Yucatan, Campeche and Quintana Roo. Against that, the loss of a few of Lowry’s 1930s haunts has understandably failed to trouble the locals.

I got back to the hotel feeling sadder still. There was a new guy at the reception desk. I asked if he could show me the tiny room in the tower where Lowry used to write. It’s not in the public areas of the hotel, he protested. After a lot of cajoling, and trying to explain about the novel and its meaning for me, he agreed to abandon his post to take me up into the tower.

A fire escape with a tacky gold handrail led to a door on which the beige paint was flaking, with leaves blowing across the terracotta tiles outside it. I tried the handle but it was locked. I asked him to open it. He refused – even when I offered a $20 inducement. He wanted to get back to his post. His indulging me was over. ‘It’s just for brooms and stuff,’ he said. ‘You don’t want to see that.’

Maybe I didn’t.

Comments