Goya to Impressionism: Masterpieces from the Oskar Reinhart Collection, at the Courtauld, consists of a selection of 25 absorbing paintings chosen from 207. I was disappointed but not surprised that one of the greatest paintings in the world, Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s ‘Die Anbetung der Könige im Schnee’ (The Adoration of the Kings in the Snow, 1563), didn’t make the journey from Winterthur in Switzerland. Too precious to put at risk.

There is no requirement for a collector to accumulate thematically consistent paintings. Whim, availability, opportunism, taste, connoisseurship, pleasure, accident, catholicity all play their part. The Oskar Reinhart collection is gloriously heterogeneous, a series of bonnes bouches. What is it, if anything, that perhaps connects Goya’s ‘Still Life with Three Salmon Steaks’ (1808-12) and ‘The Adoration’? The Bruegel pushes the three kings into the margin. They are crowded out of the picture. Two of them are seen from behind, kneeling at the entrance to the stable at the extreme left of the picture. The black king, Balthazar, is at the head of a queue, waiting his turn, holding his gift. The baby Jesus has been cropped, the stable halved. The centre of attention is radically off-centre. The subject of the picture is rather teeming village life in late December. It is a great accumulation of incidentals. In the foreground, a woman climbs three brick steps from the frozen river, in her right hand a bucket which has just been filled from a hole in the ice. A child is playing on the ice in a little flat-bottomed boat, the tiny oars like drum sticks. It is cold. You can tell by the forward-lean, the effort, which Bruegel brings to the walking figures. Men are cutting firewood. And the snow is falling – in sizable gouts. I think of a Pasternak poem that describes a thaw like silver cufflinks. We live in weather, inescapable weather.

There’s also a plank leaning against the side of a building. Pointlessly, insignificantly, symbolising only itself – life in its unadorned nakedness, not innocent but indifferent, unconsidered, neutral, minor. It stands for all the important unimportant things that constitute life. In James Lever’s marvellous Me Cheeta: The Autobiography (2008), there is a litany of little memories, non-entities every one: ‘the litter on [truck] dashboards that would slide over and fall out at corners, the flattened grass outside the venues’. Compare Browning’s ‘Saul’, which captures ‘the slippery grass-patch’ at a tent’s entrance. In ‘Home-Thoughts, from Abroad’, Browning makes over to us ‘the brushwood sheaf/ Round the elm-tree bole are in tiny leaf’. The very texture of unnoticed life, remarkably unremarked.

The plank stands for all the important unimportant things that constitute life

And here we have Goya’s three salmon steaks, a dark orange-pink, with their skin like silver-mesh watch-straps. A raw trinity, three graces plumped together, but unidentifiable, anonymous, unassuming, life itself. Impossible not to recall Manet’s ‘Ham’ (c.1875-78) or his white asparagus paintings, a single sprig on marble and the bunch commissioned by Charles Ephrussi of The Hare with Amber Eyes. All three were painted only a few years before Manet died of syphilis. He knew, therefore, what was coming, what would be lost. He felt for those suddenly precious trivia – already missing them. The long-suffering invalid Heine made a famous farewell in a letter of 27 November 1823: ‘With the last breath all is done: joy, love, sorrow, macaroni, the normal theatre, lime-trees, raspberry drops, the power of human relations, gossip, the barking of dogs, champagne.’ The telling items in this apparently indiscriminate list are specific and trivial – macaroni, raspberry drops. A plank. Three salmon steaks.

You might think American pop art was underpinned by the same realisation that it is the small things, the rich impoverished details, that make up life. But I think Warhol, for instance, saw the ordinary as depleted, affectless, banal. As television, distanced, diminished to a small screen, life in black and white and drained greys. As tedious, as static, as repetitive as a test card.

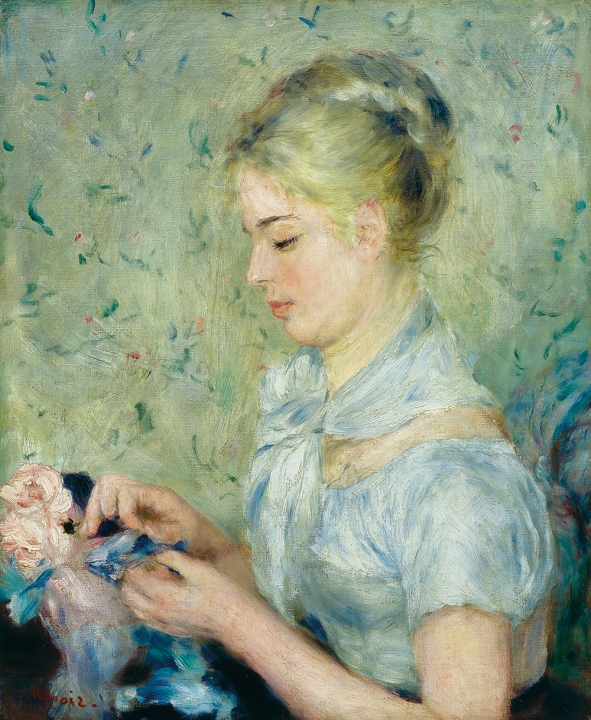

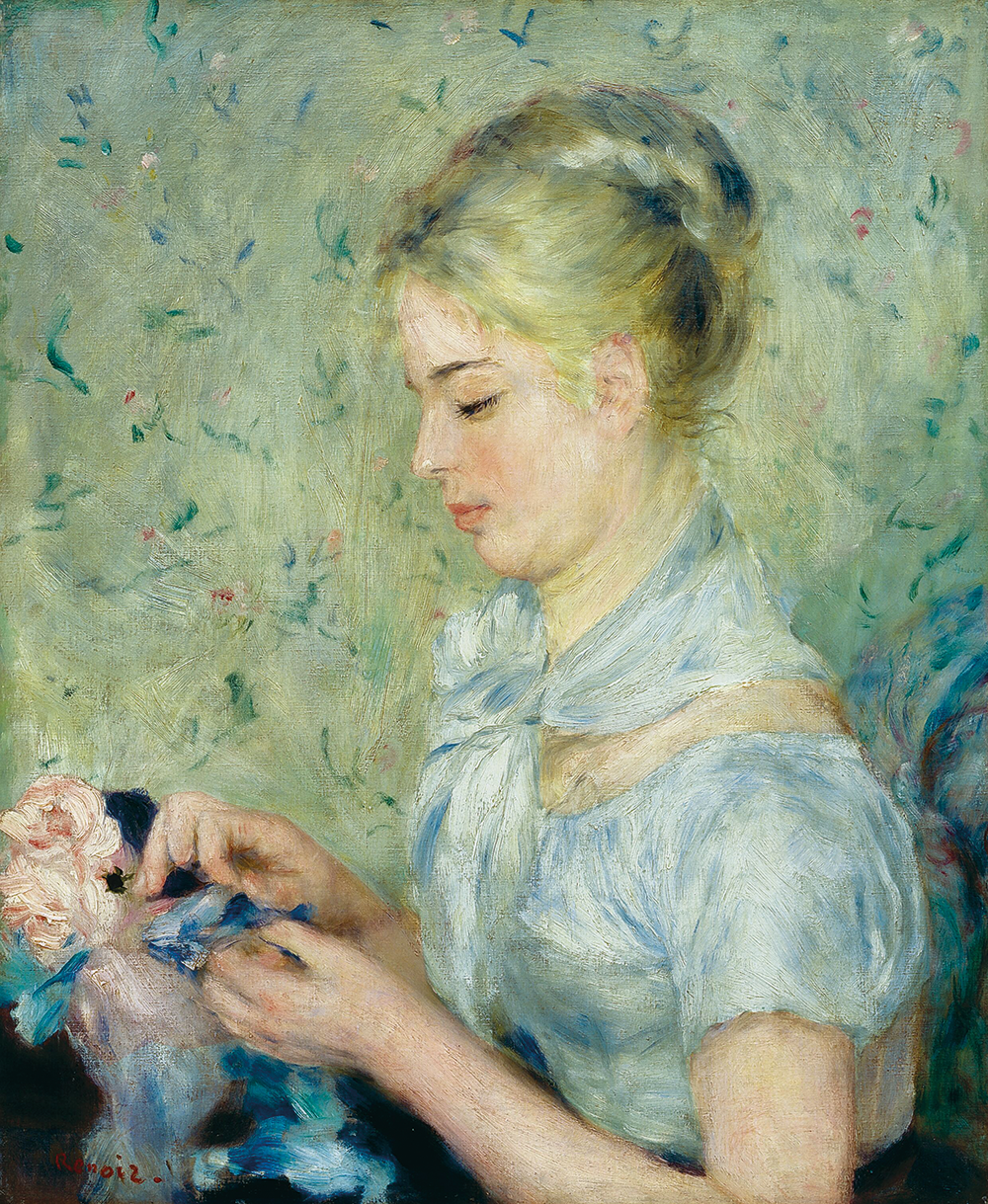

Quite unlike ‘The Milliner’ (c.1875), one of three fine Renoirs, which captures the working hands, confident and deft, in the process of sewing, the gathered right-hand pushing against the evident resistance of the material; the loose wisps of hair at the nape of her neck; and, at the very corner of her mouth, the hint of a faint moustache, soft as mink, subtle, erotic. Manet’s ‘Au Café’ (1878) depicts three beer drinkers, crammed together in their buttoned-up overcoats. The man in the middle leans back, his dashing moustaches flamboyant antlers, his cane at an angle. The woman nearest us has the same chub lips as Manet’s ‘Marguerite de Conflans wearing a Mantilla’ (1873), her expression vacant on the verge of stupidity, a kind of unthinking emptiness, never painted before, but often evident in real life. Someone who is miles away. On the table, isolated, a ridged glass container, filled with matches, to be struck against the ribbed sides – recorded and rescued from oblivion.

‘Barges’ (1870) by Alfred Sisley may seem obviously pictorial but actually the barges are seen from the rear, so we can see their enormous rudders – great barn doors, the rudimentary backsides of boats – well out of the choppy, leafy curls of the water.

Not everything works. There is a dull early, surprisingly unpromising Picasso, and a poor early Gauguin, ‘Blue Roofs’ (1884), which includes two awkward, workman-like figures, one with a cape folded over his shoulder, bottom left, the other, bottom right, walking with evident difficulty, afflicted with rheumatoid arthritis. Running concurrently with the Reinhart is an exhibition of drawings made by the poet Henri Michaux (until 4 June), under the influence of mescaline, a depiction of the ‘neural dance’. One is a pink carpet of faces, but mostly they are tight crawling lines, dense with introspection and obscurity. They left me untouched. One black swirl reminded me of an Alice Oswald description of massed starlings: ‘starlings/ whom you try this way and that like an uncomfortable coat.’ It was a relief to turn away from solipsism to representation.

Comments