The thing that the photojournalist Don McCullin likes best of all now, he tells me, is to stand on Hadrian’s Wall in Northumberland in a blizzard. He made his name in conflicts in Vietnam, Cambodia, Biafra, Uganda — hot places full of fury, panic and death — but these days he finds his greatest solace in the English landscape. I can see why he is drawn to that wild part of Britain: its isolated beauty, the feeling of being roughed up by the elements but not destroyed by them. Clean air, too: you must get a cool, fresh lungful up there.

He’s 80 years old in October: talking to him at home in Somerset, I get the sense he’s been coming up for air all his life. There wasn’t much oxygen, either physically or intellectually, where he grew up, in a damp, two-room tenement home in London’s Finsbury Park. His father, a gentle man, was permanently invalided with chronic asthma exacerbated by the coal-fire smog of the era: ‘He couldn’t walk very far or breathe very well.’ He loved his father dearly — ‘he meant the world to me’ — and his death, when McCullin was 14, was a crushing blow. ‘It made me aggressive,’ he says. ‘I said, “I’m going to give up God.”’

He was left with his two younger siblings and his mother, a fiery, strong woman who was often primed for a scrap. ‘When she gave you a clout you knew what time of day it was.’ Was he close to her? ‘Too close. I found her oppressive, really.’ His dyslexia made learning difficult, and he used to play truant and go and hunt for grass snakes and birds’ eggs at the end of the Piccadilly line. He went to work on the railways at 15 to support his family.

He’s not nostalgic for post-war Finsbury Park, with its fug of ‘bigotry and ignorance …I always felt as if somebody was treading on my windpipe.’ Still, it gave him some ineradicable qualities. Toughness, certainly: on foreign assignments McCullin held his nerve in circumstances of unimaginable stress. It also taught him what he didn’t like: bullies, in and out of uniform.

It was Finsbury Park, too, that gave him his first big break, when his photograph of the street gang that he used to hang out with, the Guvnors, was accepted by the Observer. The picture hangs in his most recent exhibition, at Hamiltons Gallery in Mayfair. It is blown up big, the better to show its precocious sense of structure. The boys, elegantly boxed in the ruins of a bombed-out building, model delinquency in their Sunday suits: they had been caught up in a fight with a rival gang in which a policeman had been killed. The day after it was published, offers of work began flooding in.

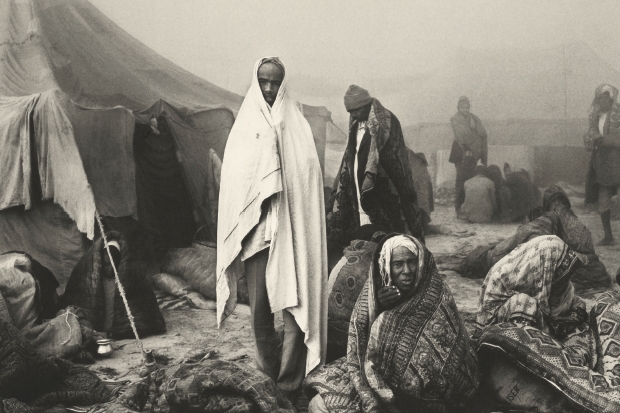

When you look at the other photographs — the ones McCullin took in war zones — what still astonishes is not simply the fact that these pictures exist, ripped from the thick of the action, but also the sureness of their composition: the shellshocked US marine in the Battle of Hue in Vietnam, his haunted face perfectly symmetrical; the female Christian Phalange fighter sinuously pitching a grenade, framed by concrete and steel.

McCullin came to loathe the cruelty of war, even while the rush of it became addictive. How did it feel to be around people such as the Phalange, as they unleashed their frenzied massacres against Palestinians in Beirut? A look comes over his face like ice glazing a pond. ‘You despise their jokes and their bestial attitude to people.’ He hit a rough patch at 52, he says. ‘I didn’t go to the Falklands and that broke my spirit. Then my wife died.’ He left the Sunday Times when Rupert Murdoch took over, and human suffering was deemed old hat. It still infuriates him.

‘The tragedy is that all these images I’ve put up didn’t really work.’ Did he think, once, they might stop war? ‘I thought it might persuade people to understand a different version of what our lives on earth were meant to be.’ But photographs can still shift the debate, I say: look at the response to the heartbreaking picture of Aylan Kurdi, the drowned three-year-old boy washed up on a Turkish beach. ‘Yes, but there hasn’t been a debate before because for the last ten or 15 years they have avoided showing those pictures.’

His job put bread on the table, but it must have been hard on Christine, his first wife of 22 years, negotiating domestic life alone with three children. ‘There’s something selfish about career,’ he says. ‘I always felt I had priority, but it’s obnoxious to think like that really.’ She died of a brain tumour at 48: a tragedy complicated by guilt, as McCullin still loved her but had left her for another woman. He says, ‘It was a bit of a cheek really, her life being stolen so quickly.’ I have noticed that he uses understatement for the memories that wound the most.

McCullin doesn’t think of himself as a writer, although he says he has enjoyed the company of some of the best: the novelist Chinua Achebe, James Fox, Bruce Chatwin. But he has the writer’s instinct for a phrase that can cut you to the quick. He describes the little albino boy in Biafra who crept up and took hold of his hand, one of 800 children he found dying in a makeshift orphanage in 1969. ‘You don’t think that was easy for me to look at that starving albino boy who had licked out the inside of this French corn-beef tin and made it look like a brand new Rolls-Royce. I know where I’m coming from; I know what I bring and what I take. I take more than I bring; I bring hope but I give nothing. That’s not the role I’m proud of.’

All McCullin had to give the boy was a barley sugar sweet. The memory still shocks and haunts him. ‘I haven’t printed his picture for years in my darkroom. It’s a terrible thing to be alone in the darkroom with that boy, as if he’s coming back. He wouldn’t have lasted for more than a few days after I took that picture.’ When he could help, he did: there’s a picture taken by another photographer of McCullin in Cyprus in 1964, carrying an elderly lady away from the fighting.

Age has landed unpredictable punches on him. It went for his heart — he had a quadruple bypass five years ago — but pretty much left his face alone. He looks much younger than his years, his cheeks almost unlined, light blue eyes quick, the mind hungry for fodder. Despite the accolades, he hasn’t drifted towards self-importance: he’s often very funny, a sharp mimic, a bit cheeky. His passion is for landscapes now, but he still has the twitchy reflexes of a news guy, alert to what Louis MacNeice meant when he wrote that the ‘world is crazier and more of it than we think’. Next up is a trip to Erbil, in Iraqi Kurdistan.

News sometimes seems to follow his footsteps: for his book Southern Frontiers in 2010, about Roman ruins, he took some beautiful, brooding black-and-white photographs of the temples at the historic site of Palmyra, now occupied and partially destroyed by Islamic State. ‘I absolutely fell in love with it. I met the director who was sadly beheaded, a wonderful man.’

Does he believe in the afterlife? ‘No I don’t. I believe that’s it. You go into the ether and that’s it.’ He sorely misses his friend and travelling companion, the conservationist Mark Shand, who died in New York last year: ‘I loved him.’ When he himself dies, he says, he wants to be cremated and scattered down by the river in the valley near his house. But for now, he says, ‘The barometer of joy is going up. Up and up.’ Why now? I ask. ‘Well, because of her really.’ He means Catherine Fairweather, his third wife, with whom he has a plainly beloved 13-year-old son, Max.

He drives me to the station and we pull up as the train is already at the platform. ‘You’ll have to hurry!’ he says, and I belt for it. I don’t think, then, about his past — full of the juddering promise of planes, close shaves and second chances — but I can see that, even in this sleepy Somerset station, something about just making it by the skin of your teeth has exhilarated him. When he suddenly reappears to shake my hand at the window just before the train moves off, he is beaming, his face lit up like a boy’s.

Comments