How do you dispose of 48 uniform volumes of the collected works of Lenin and Stalin? Pirkko Saisio and her mother hatch a plan. The books are ‘dumped into the trash bin’ by their apartment block, then coated with ‘a week’s worth of eggshells and fish guts and newspapers’. No one will find them, Mother insists. If anybody did, ‘there’s no way they’ll know they’re ours’. So Pirkko no longer has to hide the embarrassing tomes when friends drop round.

Executed during true-believing Father’s absence, Lenin and Stalin’s stinky downfall is one of many bittersweet episodes that make Lowest Common Denominator such a piquant account of a childhood and a time. A beloved Finnish novelist, playwright and screenwriter born in 1946, Saisio published this first slice of her three-volume autobiographical novel in 1998. Backlight and The Red Book of Farewells followed. It flashes back and forth between working-class Helsinki in the 1950s and the narrator’s present as overloaded writer, mother and daughter to now ailing Father.

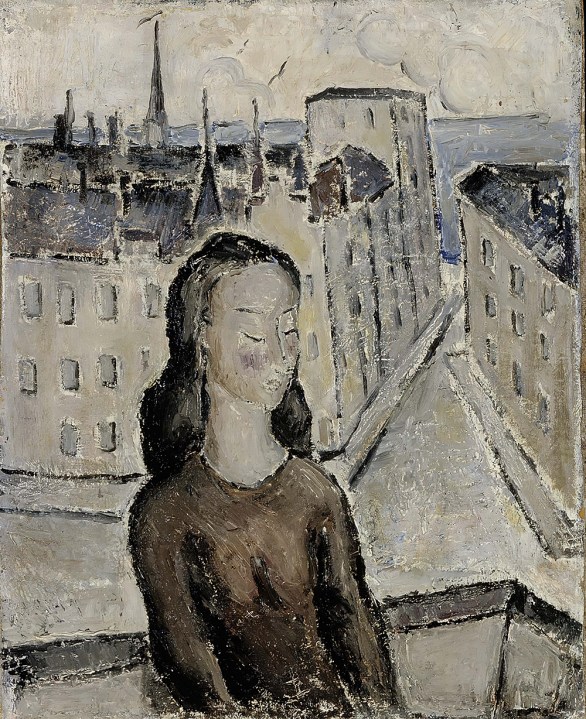

From an early age, Pirkko ‘would like to be a boy’. She falls in love with female cousins and teachers, and comes to embrace her destiny as ‘an outsider’. Penguin’s edition highlights Saisio’s position in Finland as a queer icon, and her exploration of a genderfluid childhood. Yet alongside this sexual nonconformity – embryonic in the opening volume – Saisio sketches a poignant, funny-sad picture of a communist family in Cold War Finland. Leningrad lies right on the doorstep, but Washington oceans away. Father projects propaganda films for the Finnish-Soviet Friendship Society. Above all, Lowest Common Denominator registers the birth pangs of an author. When Pirkko understands that imagined stories can be written down, ‘tearful joy rises from the deepest wellspring of her being’. Call it a portrait of the artist as a wannabe young man.

The trilogy as a whole belongs on the same fertile patch of serial Nordic auto-fiction that hosts Tove Ditlevsen (in Denmark) and Karl-Ove Knausgaard (in Norway). Compared to the latter’s ballooning confessionals, however, Saisio is terse, droll and sardonic. She shows rather than tells in dialogue-driven scenes that whip along. Their tone spans affectionate comedy (as when Aunt Ulla decides she’s related to her lookalike Queen Elizabeth II, ‘chips off the same block’), tender snapshots of the tiny rebel’s dawning self-awareness, and the present-day regrets of Father’s final days in hospital. When, as a voracious young reader, Pirkko discovers Chekhov, she can’t share his ‘idle villa life’. Yet somehow ‘the sorrow – the sorrow is the same’.

The narrator changes; so does her nation. Father, that stalwart Party comrade, studies for a salesman’s diploma and wields ‘the only briefcase’ seen on their street. Mother runs a grocery stall. While this ‘fever to move up in the world’ takes hold, elders pass on tales of Finland as a ground-down Russian colony of fragile peasant lives. Aged seven, Pirkko’s grandfather was sold as a farmhand.

In contrast to the docile blondes of her clan, Pirkko feels like the ‘inherently bad’ brunette of a fairy tale – she who ‘laughs in the beginning but dies in the end’. Worse, she yearns to be the boy ‘who spits and goes wherever he wants and doesn’t care about anybody or anything’. But she does care – not just for unreachable angels, such as dark-haired Miss Lunova the circus announcer, but for the acrobatic magic of words. She senses that ‘everything that exists in the world is waiting for me to capture it in books’.

Mia Spangenberg’s translation deftly catches this nimble, glinting prose of memory. In both substance and style, comparisons with Ali Smith may come to mind. My only regret is that the dialogue sounds Urban American. For postwar proletarian Helsinki, readers here might imagine a touch of Glasgow – even Dublin – instead.

Comments