Stand in front of ‘Fall’, a painting by Bridget Riley from 1963, and the world begins to quiver and dissolve. Something you normally expect to be static and stable — a panel covered with painted lines — undulates and pulses. In addition to just black and white, the pigments actually present, other hues appear and disappear: faintly luminous pinks and greens.

To her irritation, the artist was once told, ‘as though it were some sort of compliment’, that ‘it was the greatest kick’ to smoke dope while looking at this painting. The remark, much though it affronted Riley, is wonderfully characteristic of its epoch, the mid-1960s. We usually think of op art itself as dating from the era of Mary Quant, the Beatles and LSD.

Seurat to Riley: The Art of Perception, a jolly and entertaining exhibition at Compton Verney, Warwickshire, takes issue with that view. Op, it argues, has a much longer history. The exhibition begins, as its title suggests, with a landscape by Seurat from the mid-1880s, and it ends with a room — an 18th-century one, since Compton Verney is a Georgian mansion — enlivened with a jazzy wall painting by the contemporary artist Lothar Götz. The idea is to embed op more deeply in art history.

The term, short for ‘optical art’, originated in the autumn of 1964. It was a neat pun, originally invented by the minimalist sculptor Donald Judd, and recycled by a writer for Time magazine: remove the initial ‘P’ from ‘pop art’, and you are left with op. The name, and what it stood for, quickly swept not just the art world, but also the places where people lived and shopped.

It appeared on dresses, wallpaper, handbags and knick-knacks. When Riley turned up for the opening reception of The Responsive Eye, a mammoth global survey of op-type art at the Museum of Modern Art the following spring, she was appalled to find that half the grandes dames of Manhattan culture were clad in rip-offs of her paintings.

The Responsive Eye included dozens of artists, including Victor Vasarely, the French-Hungarian painter usually credited with being the father of op, and many from Latin America. For a year or two, op was everywhere. It seemed to catch the atmosphere of the times: futuristic, imbued with the spirit of Harold Wilson’s technological white heat and yet simultaneously fun, not to say a bit trippy.

But what actually is op art? Considering that question is rather like looking at Riley’s ‘Fall’. The more you think about it, the more everything that seemed solid and straightforward starts to shimmer and dissolve.

Right from the beginning Riley herself disputed the idea that she intended to make ‘optical art’. Her individual style had emerged from studying Seurat, the French post-impressionist who broke down the forms of his pictures into dots of pure colour. Riley’s breakthrough came from applying the lessons she had learnt from Seurat’s pointillism, and applying them to abstract painting. The result was abstraction with heightened wattage: snap, crackle and op.

Riley, however, was adamant that her work was not derived from psychological research into ‘optical illusions’, nor was it — as many at the time assumed — anything to do with mathematics or science. She had been influenced by Paul Klee, Mondrian and Seurat, not by Vasarely.

If you take Riley out of the mix, there isn’t much left of op. That is one of the conclusions prompted by the exhibition at Compton Verney. Riley is the unquestioned star of the show. Her works dominate most of the galleries; in the ones where there isn’t a Riley you feel something is missing. Vasarely’s pictures, in comparison, do look a bit like designs for handbags.

Josef Albers’s ‘Homage to the Square’ is pleasant, but dull: three squares arranged inside one another in differing shades of red. Or rather, one ‘Homage to the Square’ would be fine; but Albers produced hundreds, collectively amounting to one of the most numbingly repetitive series in art history (a title hotly contested by Damien Hirst’s endless dots, which are not in the exhibition but are a bit op).

The most striking non-Rileys on display are by Peter Sedgley. His ‘Corona’ (1970), concentric circles of bright but blurred colour, does give the feeling of staring at an electric light (if not actually the Sun). But nothing else quite has Riley’s impact, precision and fastidious elegance.

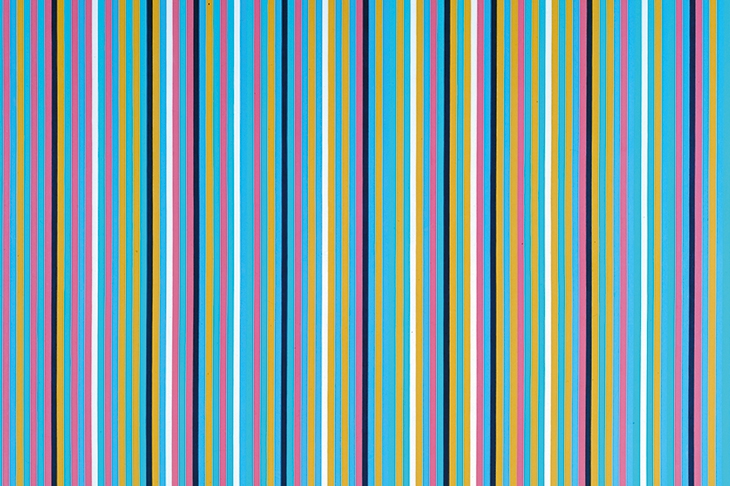

After the 1960s, her work became calmer. The later pictures no longer ripple and swirl, but they continue to provide a frisson unique in art: a sensation of glitter, brilliant light and movement. Perhaps it’s best to think of her as one of those one-off individualists in whom Britain seems to specialise. After all, painting is always an art of perception.

Comments