‘It’s chess. We’re all prima donnas.’ You can hear it spoken with a wink in the Netflix miniseries The Queen’s Gambit, released two weeks ago in seven episodes of about an hour. My heart swelled to hear the game’s essence so appreciated: of course nothing else matters when you’re playing chess. So yes, we are prima donnas, thank you, and roundly indulged by this fine TV series, which is based upon the novel of the same name by Walter Tevis, published in 1983. (My edition includes an endorsement from Lionel Shriver on the cover.)

Anya Taylor-Joy is mesmeric in the role of Beth Harmon, the novel’s troubled hero. Beth’s grim childhood at the Methuen Home for Girls, an orphanage in Kentucky, is assuaged only by the tranquilisers they prescribe the children (it is set in the 1950s), and her chess mentorship by a taciturn janitor in the basement. After her adoption, her talent blossoms and she bounds up the ranks at state, national and international level to set her sights on (fictional) Russian World Champion Vasily Borgov, all the while battling her personal demons and addiction to downers. Her character certainly owes much to Bobby Fischer, but a less well-known influence is (I suspect) the glamorous Lisa Lane, who was US Women’s Champion in 1959 and appeared on the cover of Sports Illustrated in 1961, well before Fischer in 1972.

Genius and madness, Americans vs Russians. Typically, chess on screen gets subsumed by some well-worn theme. The Queen’s Gambit brushes up against those, along with addiction, sexism and the like, but the series is elevated by its willingness to dwell on the game’s eccentric characters, bohemian lifestyle and hidden psychological complexities. Do you hit the books before that crucial game, or cleanse the mind? Does it throw you off, or encourage you, when your opponent is a jerk, or disarmingly courteous? Is it awkward to encounter an opponent away from the board?

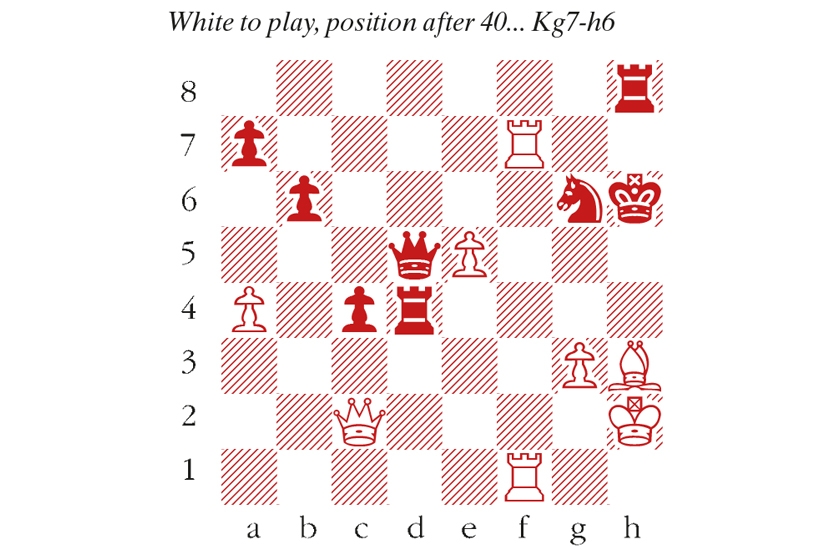

Plenty of chess is played in The Queen’s Gambit and the director (Scott Frank) consulted with American expert Bruce Pandolfini and Garry Kasparov to get the details right. (Pandolfini also featured in the 1993 film Searching for Bobby Fischer/Innocent Moves, and advised Tevis on the original book.) Almost all the games are based on famous ones played by masters, such as that shown in this week’s diagram, featuring a beautiful queen sacrifice by Soviet master Rashid Nezhmetdinov. Just as important (and even harder to perfect) is the way in which the actors sit and move the pieces. You wouldn’t have a rasping mobster fumble their cigarette like a teenager, and nor should a grandmaster handle their pieces ineptly. Barring a few infelicities, The Queen’s Gambit gets it right, and the games are staged with considerable imagination.

It’s all dressed up in beautiful period styling. The clothes, the furniture, the cocktails and the chess. At least for me, for a few precious hours, nothing else seemed to matter.

Rashid Nezhmetdinov — Genrikh Kasparyan

Riga, 1955

41 Qxg6+!! Kxg6 42 R1f6+ At first sight, the combination looks only good enough for a draw by repetition. But three nifty switchbacks by the rooks (Rf6-f5, Rf7-f6 and Rh5-g5) weave a mating net. 42…Kg5 43 Rf5+ Kg6 44 R7f6+ Kh7 45 Rh5+ Kg7 46 Rg5+ Kh7 47 Bf5 mate

Comments