For some months now it has been apparent that the greatest threat to Nicola Sturgeon’s position as the uncontested queen of Scottish politics lay within her own movement. Opposition parties could — and did — criticise the Scottish government’s record in government but their efforts were as useful as attempting to sack Edinburgh Castle armed with nothing more threatening than a pea-shooter.

Meanwhile, in London, Boris Johnson and his ministers appeared determined to do all they could to inadvertently bolster Sturgeon’s position. As Douglas Ross, the leader of the Scottish Conservative and Unionist party complained, ‘the case for separation is now being made more effectively in London than it ever could be in Edinburgh’. The last 17 opinion polls conducted in Scotland have each recorded a majority for independence.

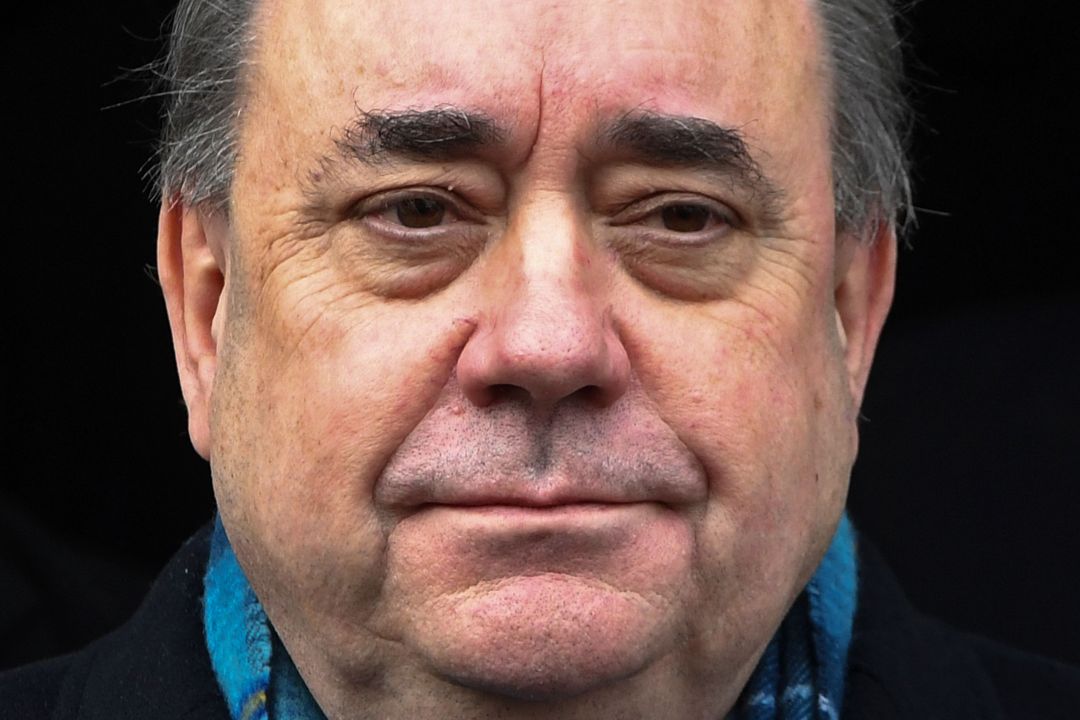

Only one spectre haunted Sturgeon; only one man appeared to have the capacity to inflict a serious, and perhaps even fatal, blow upon her. That man is her predecessor: Alex Salmond. The fall-out from Salmond’s trial — and acquittal — on a dozen charges of sexual assault has been a slow-moving but extraordinary drama to which too little attention has been paid in Scotland, let alone the rest of the United Kingdom. It is a complicated and often confusing tale and also a grim and sordid one. And it bears some exploration, for it may yet have some modest impact on British political history.

It begins, in one sense, in late 2017. In the wake of the Harvey Weinstein affair, the #MeToo movement sweeps the world. It reaches Westminster where it claims the career of Michael Fallon, the defence secretary and it reaches as far as Edinburgh too. In November, Mark McDonald, the minister for childcare in the Scottish government, is discovered to have sent what are deemed ‘inappropriate’ texts to women. He is forced to resign as a minister. And speculation mounts that, if he is also compelled to resign his Aberdeen Donside seat, Alex Salmond might be interested in contesting the ensuing by-election.

Salmond’s supporters argue that Sturgeon considered this an intolerable threat to her own position. Salmond, they insist, had to be stopped and by any means necessary. Sturgeon’s allies believe this is a nonsensical interpretation of history, though they also acknowledge that the first minister had wearied of her predecessor. She, not him, was the boss now and his occasional intimations she was merely the SNP’s chauffeur were unwelcome. Besides he had, in her view, tarnished his own standing by agreeing to host a chat show on RT, the Kremlin-backed propaganda outlet formerly known as Russia Today.

In any case, in late 2017, Nicola Sturgeon, in conjunction with Leslie Evans, the permanent secretary and Scotland’s most senior civil servant, decides that the Scottish government’s policies on sexual harassment and related matters require updating. They insist a new policy should include measures capable of addressing historic complaints. This is to include allegations against former ministers.

During this process, two women raise ‘concerns’ they had in terms of their experiences with Alex Salmond. These concerns later calcify into ‘complaints’. The Scottish government begins an internal investigation. This is the beginning of a process that may yet destroy Nicola Sturgeon and certainly will if Alex Salmond has his way.

At this stage — early 2018 — Sturgeon insists she was unaware that any complaints had been made against Salmond or that these are being investigated by her civil servants. She told the Scottish parliament she first learnt of the complaints against Salmond on 2 April 2018, when he asked to meet her to discuss a matter of pressing concern.

Awkwardly, that account — repeated on multiple parliamentary occasions — was contradicted by sworn evidence given by Geoff Aberdein, Salmond’s former chief of staff, during the criminal trial. According to Aberdein, and since confirmed by Sturgeon herself, he met the first minister on 29 March 2018, where he raised the complaints against his former boss with a view to organising a meeting between Salmond and Sturgeon where they could be discussed further. According to Salmond, Aberdein was informed of the investigation by Sturgeon’s own chief-of-staff in early March 2018. At this stage, Sturgeon insists she was still unaware of the investigation.

Last October, Sturgeon — a notoriously meticulous and detail-oriented politician — claimed she had ‘forgotten’ about this meeting with Aberdein. ‘From what I recall,’ she told parliament, ‘the discussion covered the fact that Alex Salmond wanted to see me urgently about a serious matter, and I think it did cover the suggestion that the matter might relate to allegations of a sexual nature’.

‘The impression I had at this time,’ she continued, ‘was that Mr Salmond was in a state of considerable distress, and that he may be considering resigning his party membership’. In fact, Salmond wished to lodge his objections to the procedure under which he was being investigated — a process, he claims, that did not allow him an opportunity to know, let alone rebut, the charges made against him — and to press his claims for the complaints to be subjected to an arbitration process. This request was rejected by the Scottish government and Salmond subsequently informed Sturgeon he was seeking judicial review to determine the lawfulness of the government’s process.

Salmond might be a piece of work but that does not in itself make his claim the first minister is a liar a fraudulent one

Sturgeon continues to insist she was never involved in this process, having recused herself from it. Despite the awkward, indeed the abhorrent, nature of the situation in which she found herself, she owed it to the complainants to allow the investigation to run its course. That investigation concluded and, on 21 August, a police spokesman said: ‘Police Scotland was instructed by the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service to investigate potential criminality’. Two days later, the Daily Record revealed that Salmond was the subject of a police investigation. The source of that leak has never been found.

By late 2018 it was clear, even to the Scottish government, that Salmond’s judicial review was likely to succeed. The government’s own counsel warned that the government was almost certain to lose. Yet Sturgeon’s officials pressed on regardless, even though the official investigating the complaints against Salmond had previously come into contact with the women lodging complaints against the former first minister.

In January 2019, the government conceded the issue. Salmond was triumphant and later awarded more than half a million pounds in costs. To this day, Sturgeon insists that the ‘appearance’ of bias that might have prejudiced the investigation should not be confused with any actual bias. For her part, Leslie Evans, the permanent secretary, sends a text to another official noting that ‘We may have lost the battle but we will win the war’. The government line is that this should be understood in the general context of #MeToo and not as a specific reference to Salmond.

And then a staggering development: on 24 January 2019 Salmond is arrested and charged with 14 offences of a sexual nature. These include one charge of attempted rape and another of sexual assault with intent to rape. A dozen of these charges will make it to court. The breadth, depth, and seriousness of the charges shocks even Salmond’s inveterate opponents. Scottish politics suddenly feels very different. No-one quite knows what to expect.

But few people outside Salmond’s immediate circle anticipate what actually happens: on 23 March 2020, Salmond is acquitted on all counts. Outside the High Court in Edinburgh, he vows to avenge himself on those he believes have wronged him. ‘There is certain evidence I would have liked to have seen led in this trial,’ he says, ‘but for a variety of reasons, this was not possible. Those facts will see the light.’

In one sense, however, the damage is already done. Salmond’s reputation is already trashed; the question no-one can yet answer is whether or not he will succeed in bringing down his successor and with it, just perhaps, the Scottish National Party’s ambitions to lead Scotland into the body of the United Nations — and the European Union — as a newly independent state.

By his own admission, Salmond is ‘no angel’ and in court his own lawyer acknowledged that Salmond could have been a ‘better man’. With regard to a charge of sexual assault with intent to rape, he conceded that he could have behaved in a better, more appropriate, fashion but that he had apologised for his actions to the woman in question and that this apology had been accepted. On this charge, he was acquitted with a ‘not proven’ verdict.

Multiple witnesses testified in court that Salmond’s behaviour so much concerned senior civil servants that, in the months before the 2014 referendum on independence, duty rosters were quietly rearranged to ensure a male civil servant was always part of the late-night team at Bute House, the first minister’s official residence in Edinburgh. (If true, this was an informal, undocumented, arrangement: Salmond’s defence team called witnesses who claimed to be unaware of it.)

Even so, the essential part of Salmond’s defence was that he was a creep but not a criminal; a contention given still greater credence when his lawyer, Gordon Jackson QC, was overheard telling another passenger on the Edinburgh-Glasgow train that his client was ‘inappropriate’ and ‘stupid’ and an ‘arsehole’ but not, vitally, a sexual predator. He might not be an ogre but nor was he a good man.

From this, other matters arise. If we are to take Salmond at his own lawyer’s estimation, how probable was it that his poor behaviour only became apparent once he became first minister in 2007? The incidents that formed the basis of the charges against him all took place between 2010 and 2014. Surely other people within the SNP must have had some inkling Salmond’s hands might not always be trustworthy? And wouldn’t something of this have been known to Nicola Sturgeon, Salmond’s deputy since 2004? Was it not also conceivable that Peter Murrell, the SNP’s chief executive who happens to be married to Nicola Sturgeon, might also have heard some of the whispers plenty of other people in Scottish politics had heard?

This is part of the background to the predicament in which Sturgeon now finds herself. For, remarkably and fairly or not, she is now the politician on trial. Salmond has been acquitted in the courts; now the trial of Nicola Sturgeon begins.

Lost in this are the experiences of the nine women complainers themselves. Their reputations have been traduced online and although they retain their rights to anonymity in the small world of Scottish politics there are plenty of people who know their identities. There is a sense, too, in which their anonymity, while proper, precludes the public from gaining a fuller, and perhaps more truthful, understanding of this saga.

In any case, the Scottish government’s botched handling of its investigation becomes the justification for and focus of a Holyrood inquiry into the government’s handling of historic sexual harassment cases. The committee’s remit is not to relitigate the Salmond trial but rather to explore how and why the government ended up collapsing its own case in the judicial review process and how, and why, it let down the women complainers.

It is, however, an unavoidably political process. The committee, chaired by Linda Fabiani, an SNP MSP, has repeatedly complained that its work has been obstructed by the Scottish government and, albeit to a lesser extent, Salmond. Senior civil servants, including Leslie Evans, do not appear to have the powers of recall you would associate with holders of such senior positions. The government has refused to hand over the legal advice it received during the judicial review process and has twice defied explicit parliamentary instructions it do so. This has helped foster the suspicion someone, somewhere, is hiding something more serious than mere incompetence.

But what? That remains unclear. Sturgeon is accused of breaking the ministerial code by failing to report her conversations with Salmond in the spring of 2018. She claims that the 2 April meeting at her home concerned SNP party business and had nothing to do with the government. This is hotly disputed by Salmond. The first minister’s account, he says, is ‘untrue’ and ‘untenable’ and ‘wholly false’. Salmond alleges that Sturgeon has repeatedly misled — that is to say, lied to — parliament as well as breaking the ministerial code on multiple occasions. Either of these might ordinarily be considered a resigning matter.

And first ministers have perished for less. When it was revealed that Henry McLeish, the former Labour first minister, had failed to declare income derived from the sub-letting of his parliamentary office when he was a Westminster MP, John Swinney, then leading the SNP, sonorously declared that ‘The conduct of the first minister must be beyond reproach’. I suppose it must, though it is now clear that standard was not applied to Alex Salmond and may not be applied to Nicola Sturgeon now.

In any case, the waters are made still murkier by the manner in which the SNP leader and its chief executive have contradicted one another. Sturgeon insists the now infamous meeting with Salmond at her home was a party matter; her husband, who claims to have arrived home to discover Salmond, Sturgeon, their aides, and Salmond’s lawyer, cloistered in his front parlour and thought there nothing unusual about this, insists it was a meeting about government business. It was, therefore, correct that he be kept in the dark about it. Mr Murrell’s account cannot be squared with Ms Sturgeon’s anymore than Sturgeon’s account may be squared with her husband’s.

The most plausible hypothesis — and this is merely my speculation — is that Sturgeon and Murrell believed this could be kept a party matter until such time as it became obvious it could not. At that point, nearly two months after the meeting took place, Sturgeon informed her civil servants of it though, as best we know, she did not furnish them with the details they would expect to receive of any and all government meetings.

In court, Salmond’s lawyer hinted at a dark conspiracy against his client. ‘There is something going on here,’ he told the jury. ‘I can’t prove it, but I can smell it’. Monstrous as this allegation might be — for, if true, it would mean the first minister was at the centre of an attempt to corrupt the state’s justice system — it was ostensibly given some greater measure of credibility by a brace of text messages sent by Murrell the day after Salmond was charged by the police.

The first of these read: ‘Totally agree folk should be asking the police questions… report now with the PF [Procurator Fiscal] on charges which leaves police twiddling their thumbs. So good time to be pressurising them. Would be good to know Met [looking at events in London’. A second message said: ‘TBH [To be honest] the more fronts he is having to firefight on the better for all complainers. So CPS [Crown Prosecution Service] action would be a good thing.’ Murrell now argues that the customary meaning given to the words in these messages should not apply in this instance. (The references to the CPS and the Metropolitan Police refer to reports that the Met was opening an investigation into alleged offences that might have occurred on their turf. These enquiries led to no further action.)

Although it forms no part of the Scottish parliament committee’s investigations, the backdrop to much of this is formed by a vague awareness that Salmond’s behaviour — sometimes inappropriate by his own admission — could hardly have only become apparent, or a matter for concern, once he became first minister in 2007. Perhaps this behaviour did not rise to the level of criminality, but traditionally even politicians have been held to more exacting standards than criminals.

So what, if anything, did the party know and when did it know it? One complainant testified in court that she had told the SNP in November 2017 the broad outline of an alleged incident that would lead to Salmond being charged with attempted rape. In response, a senior SNP official promised to ‘sit’ on this information, trusting that it would never require to be used. Although, again, this event does not fall within the Holyrood committee’s remit, it seems more troubling than many of the matters that do. For, remarkably, we are asked to believe that neither the SNP’s leader, nor its chief executive, were informed of this.

But then it is just as remarkable that Nicola Sturgeon and Peter Murrell are perhaps the only two people in Scotland’s political village who never heard any whispered concerns about Alex Salmond and his behaviour towards women. They heard nothing, they saw nothing and they certainly did nothing.

Sturgeon complains that some people accuse her of covering up Salmond’s deplorable behaviour even as other people accuse her of using it to destroy her predecessor. These can’t both be right, she says, and if they can’t both be right we are encouraged to think neither of them can be. This is a cute defence but not a watertight one. As a purely theoretical matter, it is quite possible for Sturgeon to have ignored Salmond’s behaviour in the past only to then, at a later date, conclude it could no longer be left in a box labelled ‘Better left undisturbed’. That is merely a hypothesis but not, I submit, an impossible one.

Thus we now endure a remarkable situation in which Nicola Sturgeon and Alex Salmond, the two most significant figures in Scottish politics this century, each complain they are the victim of a conspiracy determined to destroy them. There is an unavoidably biblical or Shakespearian tinge to this grubby, often tawdry, tale but lurking somewhere within it lies the as yet unconfirmed truth.

As a matter of politics — for, of course, politics cannot be banished from this tale — the Salmond affair is the best, perhaps last, chance Scotland’s opposition politicians have of pinning something mucky on the first minister. That explains the ever-shriller tone taken by Conservative and Labour politicians. They cannot quite be sure what is being hidden from view but they are increasingly convinced something is.

That suspicion is shared by a minority of SNP parliamentarians. Some of these bristle at being referred to as ‘Salmond’s allies’ and plenty of them are, if we are to indulge them, yesterday’s men. Those who feel Salmond has been traduced are also disproportionately likely to question Sturgeon’s approach to the national question. She insists that Boris Johnson can be bent to her will, arguing that an SNP victory in May’s Holyrood elections will give her the mandate she needs to press for a second independence referendum and the moral authority to ensure Johnson concedes it. Sturgeon’s internal critics ask why the Prime Minister would do that, given the risk he would run of losing such a referendum, and ask a simple question: ‘What is Plan B?’ To which the answer is: there is no Plan B.

The authority of the Sturgeon-Murrell axis at the head of the party was dented in recent elections to the SNP’s national executive committee in which a slew of sceptical voices were voted into positions of notional — though not always actual — influence. Sturgeon retains the support of most SNP politicians and most of the membership but her position is not as secure, internally, as it was.

In the court of public opinion, however, matters are rather different. Polling confirms that Sturgeon remains significantly more popular — and more trusted — than Salmond and, in any case, the saga has yet to penetrate the public’s consciousness. Beyond the usual suspects — inside and outside the SNP — there is as yet no great clamour for Sturgeon’s head. That reflects the manner in which the Salmond affair has been overshadowed by Covid but also the extent to which no-one has quite come up with a charge against Sturgeon that is both impressively serious and capable of being summarised in a single, pithy, soundbite.

And yet, certain problems persist. I submit that the only plausible explanation for Sturgeon forgetting her 29 March 2018 meeting with Geoff Aberdein is that she learned nothing from it she did not already know. I doubt the public cares, or can be made to care, very much about breaches of the ministerial code and I am not convinced the Scottish electorate would necessarily judge Sturgeon harshly for lying to parliament either. Some of this is baked-in to public scepticism anyway; some people will ask what the fuss is about remembering, or failing to remember, a mere meeting.

But there is no denying the peril — or the potential peril — of the situation in which Sturgeon finds herself. Salmond has little to lose, even if it seems extraordinary he might willingly pull down the house he did so much to build, while Sturgeon has everything, including history, to risk. It will strike some people, and not just women either, as hideous if the greatest victim of Salmond’s trial on charges of sexual predation proves to be the woman who succeeded him. That appears his intention, however.

There is this too: Salmond might be a piece of work but that does not in itself make his claim the first minister is a liar a fraudulent one. In the coming weeks, Salmond and Sturgeon will each give evidence in person to the Holyrood committee investigating this increasingly ugly, sordid, affair. Only an optimist would claim a satisfactory outcome in which the truth prevails is likely. There is too much at stake to allow too much daylight to intrude upon the inner workings of the SNP and the Scottish government alike.