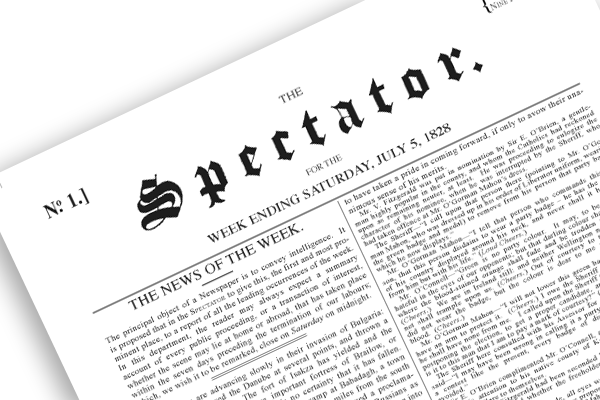

As print titles battle logistical disruption and falling sales from Covid-19, it’s worth saluting The Spectator’s long-lasting tenacity. It has appeared without fail now for 192 years, week in, week out. Its publication has continued through both world wars, numerous strikes and protests, power cuts, cholera outbreaks and terrorist attacks. Today, even as the country has gone into lockdown, it has maintained its rhythm, with staff compiling issues from their studies and kitchen tables. And next week, on St George’s Day, The Spectator will turn out its 10,000th issue, a benchmark reached by no other magazine in history.

The path has not always been easy. At the outbreak of the second world war, The Spectator’s skeleton staff were prudently moved from its Gower Street offices in London to Harmondsworth in Middlesex. But after a few days the measure proved too frustrating, and the team returned to Bloomsbury. As it happened, the Gower Street premises emerged relatively unscathed from the war, although the basement was set on fire by an incendiary bomb during the Blitz. Had the team been out of town, the fire would have spread and the whole office would have gone up in flames. Soon after, St Clement’s Press, the paper’s printers, was bombed, but the shell failed to explode and the magazine appeared that week like any other.

Throughout WWII, The Spectator was scaled down in size by governmental restrictions. The editor, Wilson Harris, chose to lower the quality and weight of paper in order to maximise the content of the magazine. He was frank with his readers about the troubles he and his staff faced:

‘In the course of Monday night the editor, with no worse than shattered windows, had to evacuate his flat owing to the presence of unexploded bombs, the assistant-editor (fortunately unhurt) had his house half wrecked, another member of the staff, with the whole neighbourhood evacuated owing to time-bombs, could not arrive at all. And so on. Of course the posts, which bring copy, are utterly unreliable. Life therefore proceeds under some difficulty, but it proceeds, and will. And if, as I say, my colleagues’ preoccupations leave some trace on the printed page, readers who have suffered something similar themselves or worse will no doubt make allowances. Carrying on will not get easier, but it is not in sight of getting impossible.’

The Spectator has witnessed several dramatic events: it survived the civic unrest of 1866 and 1887 unharmed, while its office was literally shaken by the proximity of the 7/7 terrorist attacks in 2005. Climatic events, natural and man-made, have not stopped its tracks either: it weathered the Great Blizzard of 1891, the Great Smog of 1952, the Great Storm of 1987, and the August Heatwave of 2003.

Money matters proved a little trickier: it required deep-pocketed proprietors to keep it afloat in the early 1860s – when most readers were baffled by its high-minded support of the North in the American Civil War – and in the early 1970s – when many readers became jaded by its incessant, and ever more aggressive, anti-European Market ranting.

Still, The Spectator survived the financial crisis of 1847, the Long Depression from 1873, the Great Depression from 1929, the stagflation of the mid-1970s and the three-day week, and the Great Recession of 2007-8 It survived Black Friday in 1866, Black Monday in 1987, Black Wednesday in 1992, and – if you’re prepared to give the term currency – Black Thursday last month.

Instead, industrial unrest and governmental strictures presented the magazine with its biggest challenges. In May 1926, when the General Strike stopped all printing of the national press, the paper’s staff worked through several nights to type up and print their own issue on a Gestetner duplicating machine. The resulting magazine was not pretty, but it kept the flame burning.

In the fuel crisis of February 1947, the Government arbitrarily suspended the appearance of periodicals for a fortnight. The Spectator cannily found a means of survival: it was printed on page 2 of the Daily Mail for two successive Thursdays. By turning down an earlier offer of hospitality from the Observer, The Spectator briefly had 3 million readers.

In July 1970, matters were at last taken out of the magazine’s hands by ‘a dispute in the printing industry to which The Spectator

was not a party’. As a result, the 4 July issue was rolled-over to the following week’s scaled-down issue. For the first and only time in its history, the expected appearance of the magazine was forestalled.

At times, The Spectator has been made forcibly homeless. In 1829, it was kicked out of its first premises on the Strand, at the behest of the new King’s College. In 1920, it lost its 90-year base on Wellington Street after compulsory purchase by the government. And in 1975 the magazine’s outgoing proprietor decided without notice to sell its long-standing home on Gower Street. But, neither then nor at any other time, has its staff ever left central London.

This spring, the grim hand of Covid continues to extend its lethal reach. But The Spectator meticulously charted the spread of cholera during the 1850s, witnessed the influenza pandemic of 1918-19 (and subsequent spikes) and SARS in 2003. It now – like all of us – faces unprecedented challenges. But, however the problems worsen, it would be rash to bet against its fighting spirit.

David Butterfield is a Fellow of Queens’ College, Cambridge. His new history of The Spectator is published next week.

Comments