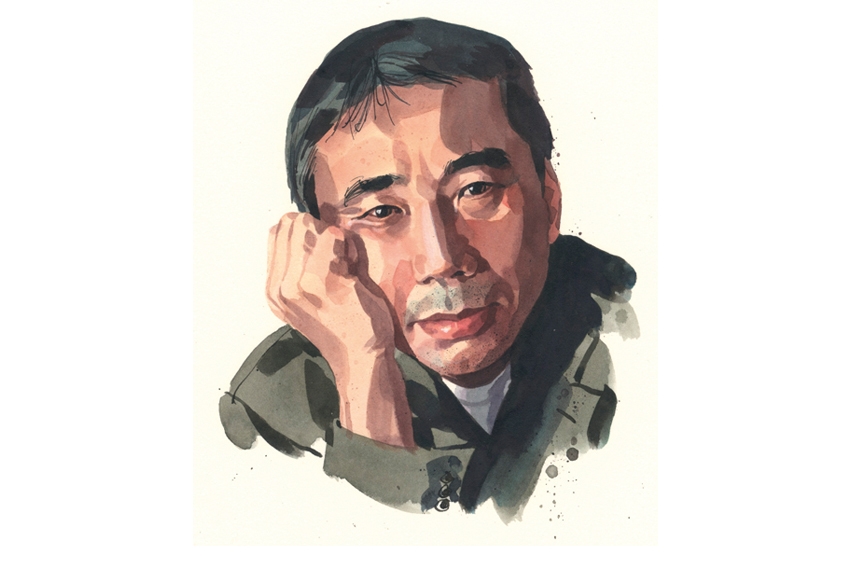

Haruki Murakami’s latest tale of good and evil has a thrilling, broad sweep, but the delicacy of his early work is missing, says Philip Hensher

The scale of the celebrity of the Japanese novelist Haruki Murakami is impossible to convey. From 1987, when his enchanted love story Norwegian Wood sold millions, he has been a huge presence in Japan. From the 1990s onwards, he has moved from being a cult favourite abroad to a general bestseller. His extravagant stories, especially Dance Dance Dance, Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World and (probably his best and most influential book) The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle introduce the fantastic into contemporary Japanese society, combining an unexpected Shinto sense of the independent life of objects with a taste for international culture, especially in music.

He has often confronted Japanese history and crises — the war in Manchuria in The Wind-up Bird Chronicle,

the Tokyo subway gas attack in the non-

fiction Underground, the Kobe earthquake in After the Quake. This enormous new novel, his first major work since the 2002 Kafka on the Shore (translated in 2005) has been an immense popular success in Japan, selling a million within a month of its publication, which is quite something for a 1,000-page work.

He is much spoken of as a candidate for the Nobel Prize. His particular vein of fantasy, engagement and a persistent humane sweetness draws huge audiences. With this novel, I think we can reasonably ask, nevertheless, whether he is as good a novelist as he used to be.

The title, 1Q84, refers obliquely, just as Kafka on the Shore did, to the work of a classic European novelist without ever bringing a comparison to the point. 1Q84 signifies an alternative version of the year 1984 — the two are pronounced the same in Japanese — which some of its characters experience. It has hardly anything to do with George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, though the comparison is occasionally evoked by Murakami.

It’s a fiction of parallel lives, and begins when its heroine, the curiously named Aomame (Green Peas) abandons her taxi on a gridlocked overpass and climbs down a service stair into a world, she discovers, which is subtly different from the one she has left. The first indication of this is the sudden appearance of a second moon in the sky, rather green. Aomame is in such a hurry because she has an appointment to murder someone — she is an assassin, hired by a wealthy dowager to kill abusive men.

In a second strand, a writer, Tengo, is hired by a publisher to rewrite the work of a teenage girl. The girl, Fuka-Eri, has produced a compelling but raw account of life within a closed commune of political idealists, and the appearance of the ‘Little People’. Tengo meets Fuka-Eri and is struck by her indifference to what is done to her work. He rewrites it, and it wins prizes and becomes an immense bestseller.

There may be some truth in Fuka-Eri’s account. She turns out to be the daughter of a commune leader of an extremist sort; one, too, on Aomame’s patron’s hit-list when it emerges that he raped Fuka-Eri. Aomame and Tengo do not meet, but their minds turn back to early lives, when Tengo, a popular boy in school, reached out towards the daughter of some religious extremists, shunned by her classmates, with the odd name of Aomame. Tengo feels that, in adulthood, she is close to him; Aomame feels a compulsion to track down Tengo.

Tengo, however, has some unfinished business to deal with: his father, a bullying subscription collector for the Japan Broadcasting Corporation, NHK — think our own unlovely TV licence-fee collectors — is lying dying in a small town elsewhere in the country. Is there a link with the strange appearance of an NHK collector who hammers on the door of so many of the characters, most of whom by now have a very good reason to cower inside and pretend not to be there? Could there be some connection with the odd way that so many characters find themselves creating strange identical avatars, sending them out into the world to do good or evil? And if so who, exactly, is talking to whom? Which of them is real and which something else entirely?

In some respects, 1Q84 is a thrilling journey, though it certainly takes its time to ratchet up the excitement — it didn’t truly grip me until 450 pages in, when the leader of the cult explains to Aomame that even though he may be the king in Frazer’s The Golden Bough who must be ritually killed for his people to thrive, his people are still going to hunt down the assassin. Electric as the scene is, and exciting as the book becomes after that point, 450 pages is a long stretch to ask a reader to wait.

And I wondered, too, about the quality of the writing, which throughout seems dismayingly thin. Of course, it is hard to distinguish the original writing in Japanese from the sins of the translators, but often one can guess which is responsible for which. It’s been translated by two long-term collaborators of Murakami, Jay Rubin and Philip Gabriel.

Gabriel seems marginally preferable, but rarely have translators so deserved Schopenhauer’s insult, that translators ‘use only worn-out patterns of speech in their own language, which they put together so awkwardly that one realises how imperfectly they understand the meaning of what they are saying.’ I don’t believe Murakami wrote anything like ‘Aomame twisted her face into a major grimace’ or that ‘Ushikawa knew that Eriko Fukada had literally shaken him to his core’.

When Rubin writes (of Fuka-Eri’s book) ‘it was no different from some of the greatest landmarks in Japanese literary history — the kojiki, with its legendary history of the ruling dynasty’. I would guess that he is clunkily incorporating a gloss which would be better provided in a footnote.

But whose is the appallingly limp reflection — ‘And this other person was a police officer! Aomame sighed. Life was so strange’? Who is the source of the atrocious bathos when a character thinks, ‘By the pricking of my thumbs/Something wicked this way comes’ and immediately afterwards, ‘Still, Shakespeare’s skilful rhyme had an ominous ring to it.’ Neither translator can write dialogue with any kind of convincing rhythm.

But it is surely Murakami himself who hasn’t envisaged the context for his conversations, how his characters realistically respond to each other, physically and verbally. They are always reported as ‘sighing’ and ‘narrowing their eyes’ — signs of a novelist reaching for stock gestures rather than looking freshly.

Murakami has never seemed quint-

essentially Japanese. It is hard to say what he has drawn from the noble national tradition, and here he seems to present the reverse of one of his culture’s abiding qualities. Visitors to Japan are always struck by the exquisite attention to beauty on a small scale — an interior, a tea-bowl, a plate of food — and alarmed by how ugly most of the cities are.

Murakami achieves the opposite effect here. It is the large design of 1Q84 that is rather thrilling, with its effects of doubles, and questions about who, exactly, is existing in a fictional created world, as well as the steady, thrumming approach of the Little People towards the human action. Architectural joins are skilfully created — I particularly commend the cliffhanger of the heroine on a motorway with a pistol jammed into her mouth.

What I missed were those exquisite turns, and lines and delicacy of mood and expression on the small scale that make Dance Dance Dance and The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle so irresistible. It is regrettable to see such a wonderful novelist abandon all but the very broadest effects.

Comments