Do you get that alarming feeling, right now, that everything is suddenly, rapidly, falling apart?

At the same time, does everything also feel strangely less real to you, as though modern life were just one big, phoney act – a performative parade of political spin, sloganeering, social-media campaigning, simulated outrage, and petty culture war point-scoring?

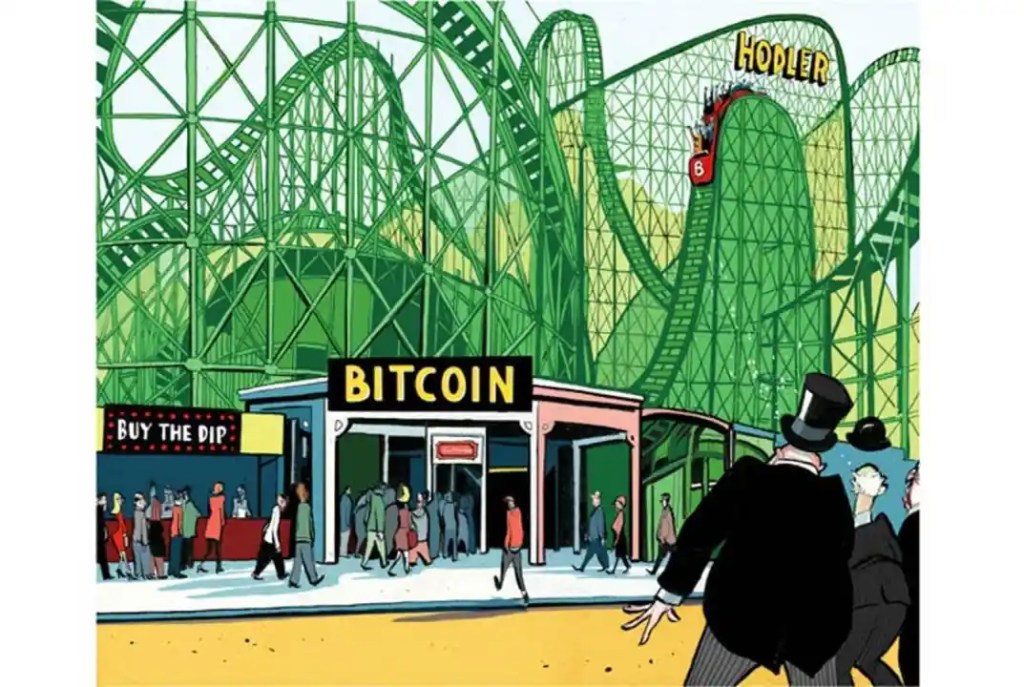

These two things are connected. We’ve spent years as a society constructing an elaborate pyramid scheme of virtual realities – from cryptocurrencies to social media influencers to startups that ‘outcompete’ each other only by posting eye-watering losses each year – all to the neglect of the real world. And now, in 2022, the real is finally catching up with us.

The word ‘virtual’ first emerged in the fourteenth century. It wasn’t until the fifteenth century though that it took on something like its present meaning: ‘being something in essence or effect, though not actually or in fact’. These early origins should immediately disabuse us of the idea that ‘virtual’ has anything to do with modern technology. Something is ‘virtual’ on the basis of its psychological effect alone, and a ‘virtual reality’ is simply any imaginary world with its own internal rules and expectations.

All games involve virtual realities. So do novels. So, too, does the experience of sitting on the Tube, rattling out WhatsApp messages to your friends – your mind as much ‘inside’ the group chat as it is the physical space of the train.

With luck, as we collectively sober up from our bout of hyper-virtualism, we’ll see a broad return to basic, physical concerns

Virtual realities, then, are as old as mankind – or at least as old as children playing make-believe. But where modern technology has made a difference in recent years is in presenting us with a vast semi-permanent network of virtual worlds. Social media, 24/7 news, online pornography, instant messaging, emails, always there in the background, overlapping and interconnecting, such that we can often go whole days without properly leaving its labyrinth. If, that is, we ever truly mentally escape it at all.

And all of this has led, over the last few decades, to the emergence of a uniquely modern form of collective madness: what I call ‘hyper-virtualism’. This is simply when the virtual realms we inhabit begin to feel more real and normal than the actual thing – when imaginary worlds begin to feel like the default, and the physical world starts to feel like the derivative. The tell-tale sign of hyper-virtualism is when we expect that, by managing things in virtual worlds, we’ll end up actually changing things in the real one, too.

All of us suffer from hyper-virtualism of one kind or another. We believe our social media personas really are our personas; that online activism really will change the world (that black square profile pictures really will stop police brutality in the States, or that policing language on Twitter really will put an end to racism). We think that good polling figures and headlines really are all that matter for a political party’s fortunes (and, by extension, the fortunes of the country); that cryptocurrencies really do have some mysterious, sustainable source of value apart from the material resources that underpin fiat currencies. Add to this the belief that the metaverse, play-to-earn games, and NFTs really will somehow create a second virtual economy on top of the physical one, rather than simply shuffling a little money from the luxury analogue market to the luxury digital one.

Arguably the web’s most significant contribution to hyper-virtualism is something we barely think about today: just how much time we now spend immersed in various forms of text.

In 1990, the average person spent between one and two hours a day reading and writing. By 2012, thanks to the internet and various forms of messaging, that had already shot up to something more like five hours a day (and of course, for many people, much more still). That’s a third of our waking lives – more time than we spend on anything other than sleep.

When so much of our experience of reality is mediated through the prism of text, we come to imagine that the words on our screens – emails, text exchanges, news websites, Twitter feeds – really are in some sense the real world itself. That is, we transform the real world into a simplified virtual world in our heads, one that can be engaged with and manipulated by text alone. To use Marshall McLuhan’s lingo, we mistake the medium, text, for the message: reality.

The effect of all of this on any one person’s psychology is subtle. Clearly, no-one literally believes that there’s no physical reality beyond their screens. But hyper-virtualism has a distorting effect, whereby different aspects of our experience are sorted into a kind of hierarchy of realness. As the writer Duncan Reyburn puts it, those parts of our lives that fall outside the virtual realm are, in some sense, increasingly ‘assumed to have no real reality’. Replicate this distortion in the minds of billions of people across the world, and couple it with, historically speaking, relative material comfort, political stability, and a massively complex globalised trade network – such that we forget how dependent we are on a few fragile physical facts – and our collective expectations, loosened from their short-term responsibility to truth, start to drift further and further from reality.

The warning signs have been building. Take the infamous Fyre Festival in 2017, founded seemingly on the premise that social media influencers could substitute for the hard work of running a physical event for flesh-and-blood humans. Or the recent ‘shock’ realisation that Bitcoin depends on huge servers — with vast environmental costs. Or the disastrous US evacuation from Afghanistan, which stubbornly refused to go along with the White House’s social-media-intern narrative.

The pandemic, of course, only compounded matters — resulting in a spasm of fantasies about metaverses, crypto-utopias, virtual real estate, and play-to-earn computer games. But eventually, as Reyburn writes, ‘reality will rip things to pieces to make the great systematisers aware of this simple fact: the system isn’t the reality.’ And so we come to 2022: the year the real fought back.

Everywhere the virtual is in meltdown. Earlier this month we witnessed the ‘shock’ collapse of the FTX exchange, wiping $183 billion off an already-collapsing cryptocurrency market. The internal currency of Axie Infinity, a game that allegedly allows people around the world to ‘play to earn’, has lost 92 per cent of its value.

The NFT market is in free fall — one ‘Bored Ape’ image Justin Bieber bought for £1.06 million in January is now worth only £60,000 (who would have thought a profile picture could lose value?). Meta has squandered £65 billion and fired 11,000 employees, even despite the much-heralded coming of legs.

Deliveroo, Spotify, and Uber are all haemorrhaging money, as it becomes increasingly apparent that their economic models are based on little more than speculation and blind hope. Even the very infrastructure of the internet itself is being called into question: online advertising, the quasi-physical reality on which so many virtual worlds ultimately depend, looks increasingly like a sham.

We’re witnessing the collapse of hyper-virtualism in the ‘real’ world, too. In politics, we saw Liz Truss and Kwasi Kwarteng’s bizarre budget: an economic plan seemingly devised in, and proposed for, an imaginary world in which the markets really love huge gambles delivered with a ‘screw you’ attitude. Suddenly, everyone seems to have noticed that infrastructure has been crumbling while we focused on the culture wars. The trains, it turns out, won’t fix themselves. The young won’t stop wanting homes. Cancer won’t just put itself on hold until a more convenient time. Contrary to the predictions of multi-millionaires, owning nothing probably won’t make us happy.

In America, several cities have attempted to reduce police numbers (following social media campaigns to defund the cops), with the surprising result of a rise in crime. Everyone on Twitter was, again, wrong about the American midterms – not least the Republicans who tried and failed to ‘meme’ their way to electoral success. And, as I write, the Qataris are burning $220 billion – 15 times as much as any other World Cup – clothing themselves in the respectability of a famous event. This is all while fans spend over £160 to stay in a ‘village’ of austere rows of gazebos, with still no official figures of how many temp workers died for the privilege.

It would be absurd to attribute all of this only to hyper-virtualism. Indeed, it would be, in its own way, a form of hyper-virtualism to assume that everything happening in the world can be explained by one self-contained system. But it would be equally absurd to think that our immersion in an ever-expanding network of self-reinforcing virtual worlds has had nothing to do with it.

So what comes next? Only a fool would attempt to predict the specifics. With luck, though, as we collectively sober up from our bout of hyper-virtualism, we’ll see a broad return to basic, physical concerns. That means politicians realising they can’t spin or meme their way to success, that infrastructure, public services, and growth come first. It’ll mean a shift, on the Left, away from identity politics back to simple, class-based economic arguments. It’ll mean our Silicon Valley overlords realising that physical innovations – nuclear fusion, the Hyperloop, graphene – can transform lives more than virtual ones.

It’s early days, but there’s been one crucial indicator over the last couple of years that change is already underway. During the pandemic, against all expectations, social media engagement actually began declining, and it’s carried on dropping ever since. Who would have guessed it? Maybe we’re all, slowly, beginning to wake up.

Comments