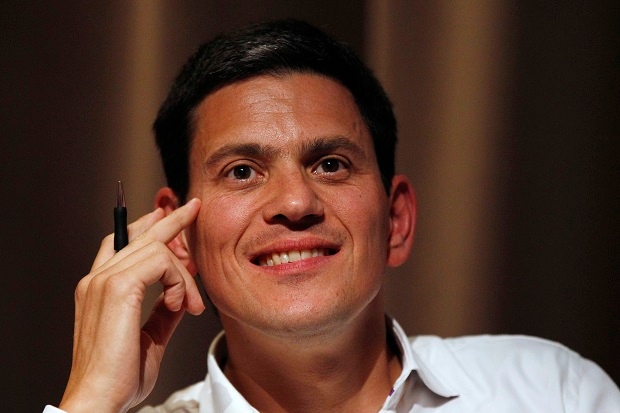

I have the impression that David Miliband’s valedictory essay in the latest issue of the New Statesman contains some really corking ideas; but I can’t see them through the words. David Miliband’s tragedy is not that he lost to his brother. It’s that he can’t express himself in plain English. He has five things to work on in New York:

1). Stop using conspicuously odd vocabulary:

‘Presidential elections are different from parliamentary systems, but there is read-across nonetheless.’

‘Read-across’…? The only thing to be said for that word is that it distracts from the platitude at the beginning of the sentence: ‘Presidential elections are different from parliamentary systems’. Well blow me.

2). Resist the urge to complicate:

‘…the tendency of markets towards inequality and instability needs to be countered by action upstream in order to curb abuse of power, and to empower citizens and employees with rights, information and control. “Predistribution” does not fit on an electoral pledge card, but the idea is right and so is the challenge of developing new ways, either through individual rights or collective organisation, to tilt the balance of power towards ordinary people.’

Would any of that fit on an ‘electoral pledge card’? And as for ‘action upstream’; well, the mind boggles.

3). Self edit. When he’s not trying to write, Miliband lapses into PPE speak:

‘It is the interaction of these global challenges that has reframed the political equation in western democracies.’

My history tutor would have put a big red mark next to vacuous padding like that.

4). Don’t try to show off with words (linked to point 2). Miliband is not afraid of trying to sound clever; but he should be because it’s difficult to be both “clever” and engaging in writing:

‘Meanwhile, politics itself is increasingly seen as broken – and not merely seen as broken but actually broken.’

There’s a complicated idea lurking there, but it’s not clear what it is. Is it that an increasing number of onlookers see that politics is broken? Or is it that politics is seen as being increasingly broken? And who is doing the seeing? Is it the public? Is it the politically interested? Or is it the politicians? And when it comes to democratic politics, is there a difference between ‘seeing’ and ‘being’? Etc.

Of course, none of the above matters because Miliband says that politics is broken. He should have left it at that.

5). Kick the abstract noun and adjective habit. Here is just one example picked at random:

‘Each of these areas of study captures social democratic concerns with equity and mutuality.’

Politics is about ideas and ideals; but it is also about reality. Miliband refers to reality, but at no point did I feel that he wholly understands it. Bad writing will do that to a reader.

Comments