When Nikolaus Pevsner dedicated his 1955 Reith Lectures to ‘The Englishness of English Art’, he left out the Scots. The English art establishment has never bothered with what was going on north of the border, which explains, though doesn’t excuse, the underrepresentation of Scottish art in the Tate’s so-called national collection.

This leaves a gap in the story of British art that the Fleming Collection has set out to fill. Since its reinvention as a ‘museum without walls’ by director James Knox – a former publisher of this magazine – the best collection of Scottish art outside a public gallery has gone on the road. Last month saw the opening of two new shows: Scottish Women Artists at the Sainsbury Centre, Norwich, and Window into Scottish Art at the Lightbox, Woking, in collaboration with the Ingram Collection.

The English art establishment has never bothered with what was going on north of the border

Pevsner came to English art as an outsider; Knox approaches Scottish art as a native. He describes his selection of 30 works at the Lightbox as ‘a dive into the Scots psyche’, which – thanks to the Reformation, the Clearances and the collapse of the great industries of Glasgow – has its dark side. But the Scottish love of colour shines through in paint.

Where England is almost uniformly green, Scotland is varicoloured: purple heather, yellow gorse, orange bracken. It was to blend in with the landscape’s vibrant hues that tartan was developed as a clannish camo, and its colours bled through to the Scottish palette. Tweed is a thread running through both shows. The 19th-century landscape painter John Knox, who includes a textile mill in his otherwise Arcadian view of the Vale of Leven, was the son of a yarn merchant and Anne Redpath was the daughter of a tweed designer. No wonder the Scottish colourists took to fauvism like ducks to water.

The influence of France – where Redpath spent 14 years – was important too. Long before the colourists went wild for the fauves, Edinburgh- and Glasgow-trained painters had been putting the finish on their art educations in Paris academies and flocking to the artists’ colony at Grez-sur-Loing to paint the sorts of spuds-and-all rural subjects English painters sniffed at. It was Jules Bastien-Lepage who popularised the potato-picking theme of Flora Macdonald Reid’s ‘Fieldworkers’, which put the 22-year-old on the map at the Society of British Artists in 1883. Born in London to Scottish parents, Reid was one of the first generation of women to attend Edinburgh School of Art, but like so many Scottish painters she gravitated to London, where she forged an independent career as a single woman.

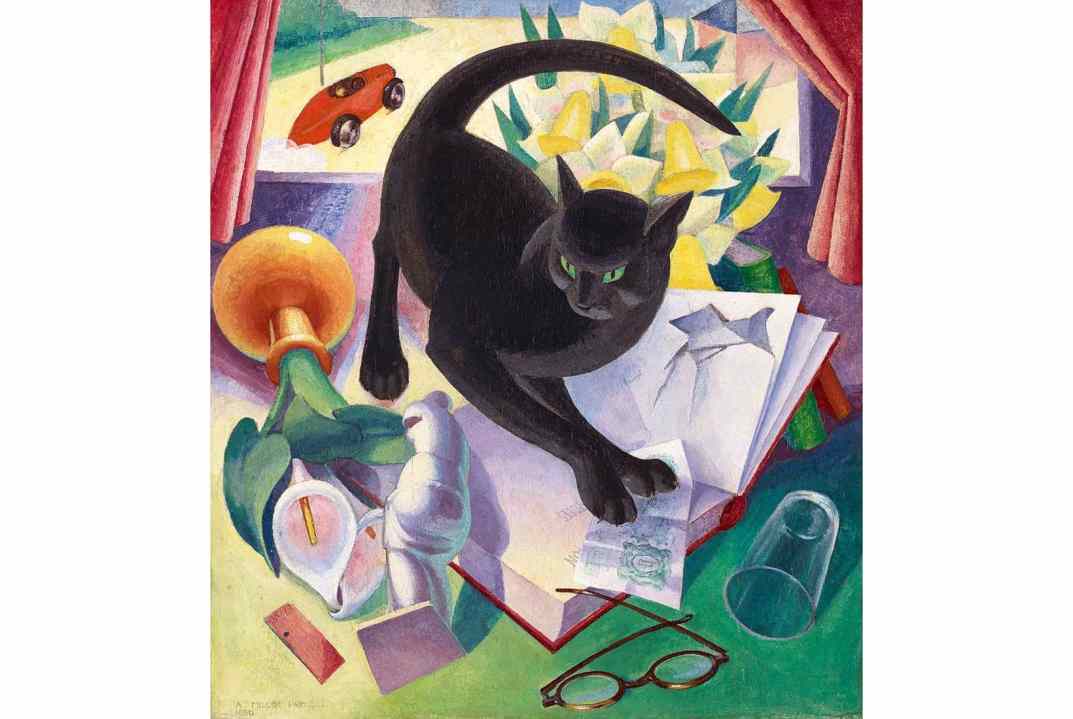

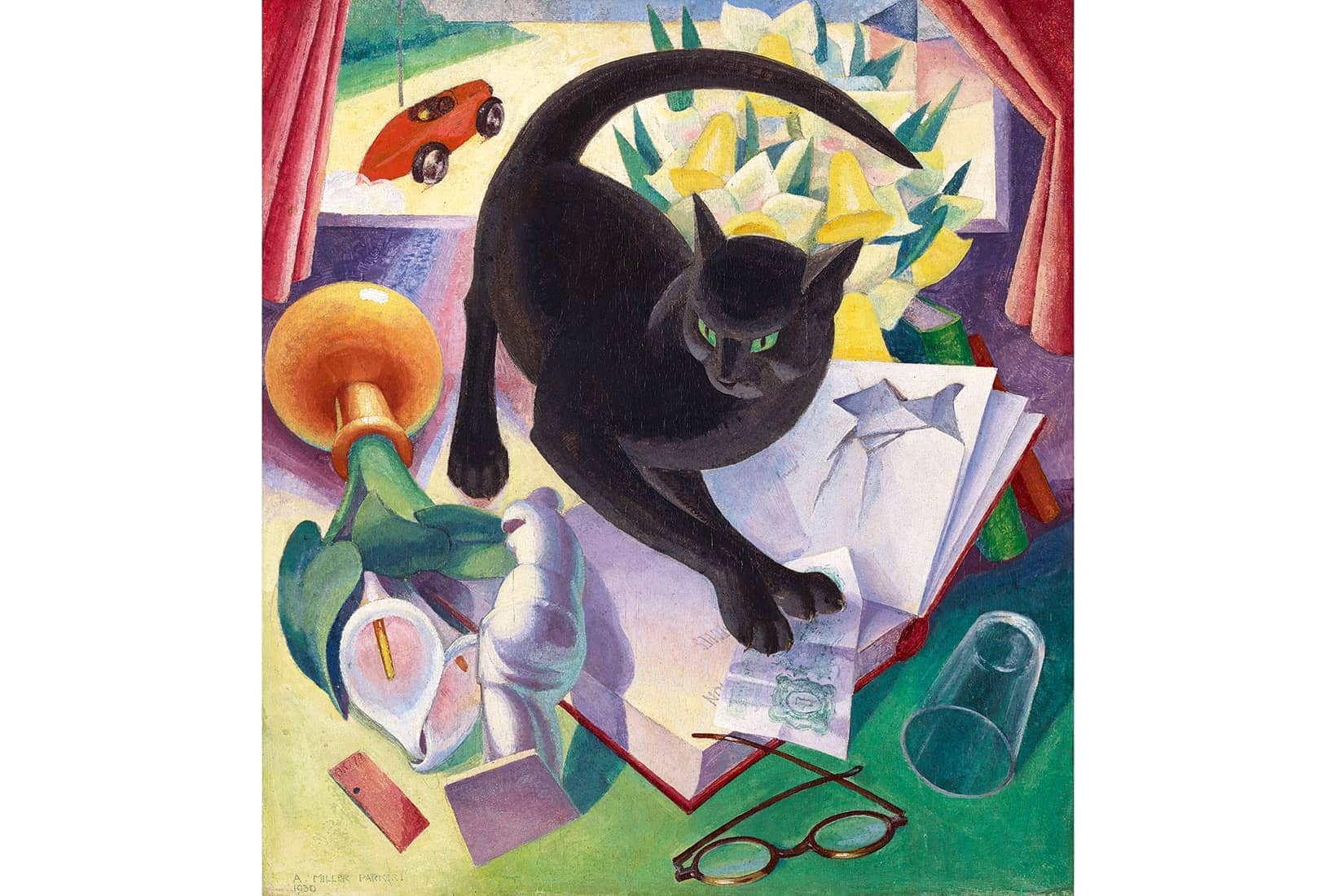

For women artists, marriage was the great enemy of promise. The Sainsbury Centre exhibition is a catalogue of casualties of the altar; even teaching careers fell victim to the marriage bar, which decreed (until 1945) that wives get back in the kitchen. Artistic marriages helped, though wives were usually overshadowed by their husbands. Not Agnes Miller Parker: in her painting ‘The Uncivilised Cat’ (1930) a vorticist moggie paws a volume of first-wave feminist Marie Stopes’s Love’s Creation after knocking a statue of Venus off her pedestal. Miller Parker’s husband William McCance later struggled with his wife’s success as a woodcut illustrator for the Welsh Gregynog Press.

If Parker had claws, other women had patience. In 1934 Redpath left her architect husband David Michie in France and returned to Scotland with their three children; she was 50 when she had her first London show in 1946. Her solution to domestic confinement was to paint still lifes; Mabel Pryde Nicholson, wife of William and mother of Ben, paid her four children to pose. As a lesbian, Joan Eardley was unencumbered by children; she painted her ragamuffin neighbours from Glasgow’s Townhead tenements before taking herself off to the remote Aberdeenshire fishing hamlet of Catterline to pit her expressive brush against the cliffs and the sea. In ‘Two Painters in a Landscape (Margot & Joan)’ (1960), her friend Margot Sandeman from Glasgow School of Art records the two women painting on Arran in the company of two sheep. It’s the diametric opposite of a swagger portrait. As Eardley remarked: ‘You really have to be tough in this game.’

Caroline Walker is one of a new generation of women artists reclaiming domesticity as a subject: she spent lockdown painting intimate domestic scenes of her mother table-laying and candle-lighting. It’s the painters who steal both these shows. By comparison with Walker’s atmospheric images, Turner Prize winner Charlotte Prodger’s monochrome reproductions of lionesses from the British Museum’s Assyrian reliefs – said to symbolise queer desire – are colourless. Prodger is English, trained in Glasgow but born in Bournemouth. The young Dundee-trained Sekai Machache, born in Zimbabwe but raised in Scotland, is a worthier heir to the Scottish tradition, describing herself as a painter at heart. A ghostly photograph at the Lightbox showing Machache dancing at sunset in an Arthurian bell-sleeved dress reflected in a Flow Country peat bog rekindles the romance of William Orchardson’s ‘Ophelia’ (1874) – the standout painting of this brief introduction to the Scottishness of Scottish art.

Comments