All great diarists have something intensely silly about them: Boswell’s and Pepys’s periodic bursts of lechery and panic; Chips Channon’s unrealistic dreams of political greatness leavened with breathless excitement over royal dukes and handsome boys; Alan Clark’s fits of romantic, almost Jacobite, dreaming; James Lees-Milne’s absurd flights of rage. I dare say the mania that drove the Duc de Saint-Simon in his demented campaign against Louis XIV’s attempts to create a place in court hierarchy for his bastards seemed ridiculous to his more sober contemporaries. Often the silliness comes from a mad overestimation of the writer’s ability. There is no more fascinating diary than Benjamin Haydon’s. He was an indifferent painter who never achieved the success he dreamt of. But in every sentence of his diary it is apparent to us what he himself never realised: that, though a painter of mediocrity, he was a writer of genius.

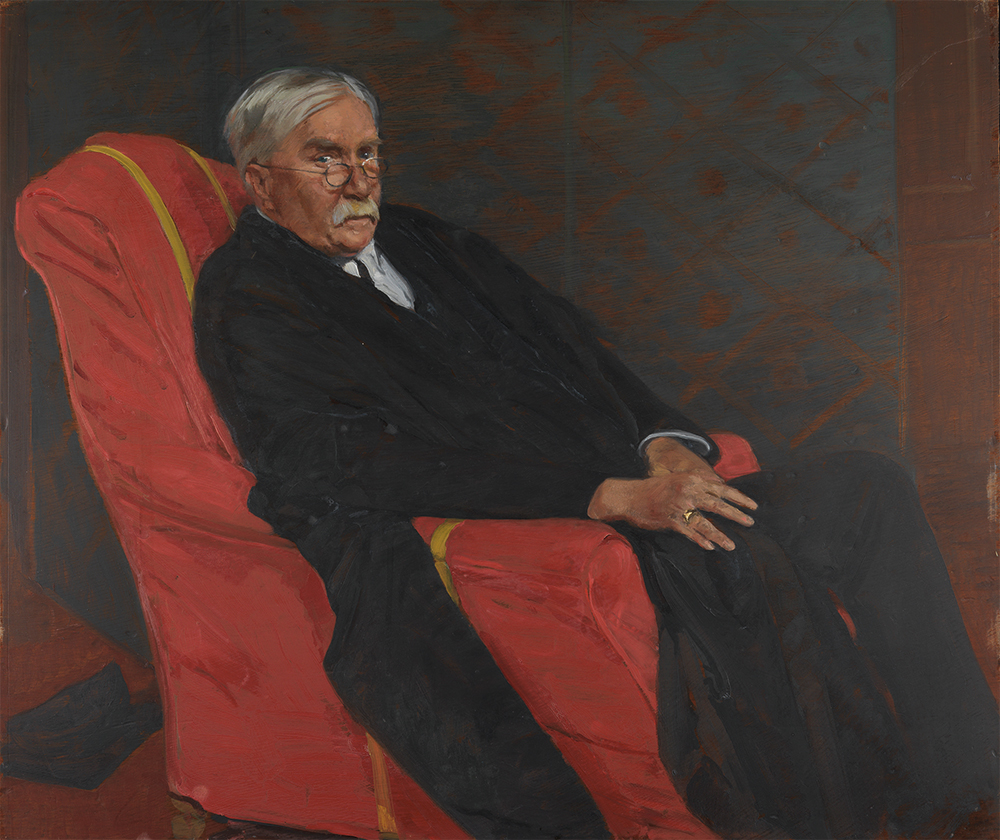

A.C. Benson, born in 1862, had the sense to make arrangements for his diary to be published after his death. The rest of his writing, with the possible exception of ‘Land of Hope and Glory’, pales to insignificance next to it. His published work is astonishingly bland. There is a screamingly funny parody of him by Max Beerbohm in A Christmas Garland: ‘More and more, as the tranquil years went by, Percy found himself able to draw a quiet satisfaction from the regularity, the even sureness, with which, in every year, one season succeeded to another.’ (Having read Benson’s staggeringly tedious Watersprings, I can report that Beerbohm does not exaggerate.) The diary, on the other hand, stretching to more than four million words, is vivacious, beadily observed and takes advantage of Benson’s position as a favourite of the great. In this beautifully edited two-volume selection by Eamon Duffy and Ronald Hyam we see what a well-placed diarist can do.

Benson was an irregularity at the heart of Victorian society, guaranteed respectability by being the son of an Archbishop of Canterbury. That archbishop, however, had his odd aspects. He proposed to his wife when he was 23 and she was 11. When they married, it soon became apparent that she was lesbian in tendency. All six of their children were lesbian or homosexual, including Fred, the sunniest of them. (Georgie, in his Mapp and Lucia novels, must be a self-portrait.) Arthur was at the centre of things, a pillar of Eton and later Master of Magdalene College, Cambridge. Queen Victoria liked him well enough to invite him to a Frogmore mausoleum service in 1900, and he later edited her letters. He went everywhere, but the degree of his waspish indiscretion was only apparent in the diary. (One of his many curious observations was that Edward VII’s heels ‘project a long way behind his ankles’.)

Cambridge University life was less demanding then than now. When Benson first arrived at Magdalene to lecture on English literature, it had only 33 students and four Fellows. He was, nevertheless, fantastically industrious, publishing more than 20 books by his early forties as well as writing the diary and as many as 40 letters every morning. Somehow this still left time for the business of getting out and paying close, sometimes unforgiving, attention to his world. There is no witness like him.

One of the joys of the diary is its engagement with the trivial squabbles of Cambridge University

One of the joys of the diary is its committed engagement with the trivial squabbles of Cambridge. In May 1914 a row erupted. The Fellows of Magdalene found that their garden had been colonised by the Master, who, without asking, had let his children keep their chickens in it. The dispute – ‘this wretched business’ – ran on for months, gloriously chronicled. When war broke out shortly afterwards, hostilities were on much the same scale.

It’s the dedication to the utterly insignificant, especially when Benson encounters celebrities, that gives the diary its special flavour. There is the visit to the elderly poet Swinburne, long withdrawn from society and living under the guardianship of Theodore Watts-Dunton. The eccentric household, unused to entertaining a guest, provides an unforgettable set piece. A pair of Swinburne’s socks were draped over the fender in the drawing room: ‘“Stay!” said Swinburne, “they are drying.” “He seems to be changing them,” said W-D.’

Certainly Benson was absurdly rapturous in important company. ‘I forgot to say that a great and memorable moment was the bringing in of a glass of lemonade for the Queen.’ But for the most part he saw things clearly. He was often in a position to record credible anecdotes at one remove – for instance, Mrs Gladstone irritating her husband on his deathbed by ‘tripping into the room’ and saying ‘You’re ever so much better’, when Gladstone was set on striking noble final attitudes.

The outbursts of judgment are often bizarre. The King of Portugal is ‘a very common-looking young man’. Belloc and Chesterton ‘really ought to be more ashamed of looking so common’. Many of Benson’s confident dicta would have been considered stuffy even by Victorians: ‘Women ought never to run on the stage. One is inclined to throw an orange at them.’ But he would often give the benefit of the doubt to a truly beautiful young man. The diary becomes steadily more open about the pleasures of conversation with intimates such as the young George Mallory, the great mountaineer. Some people evidently noticed Benson’s partiality; he was a sitting target for a slutty operative on the make like Hugh Walpole.

What really elevates the diary is the vividness of the prose. Harry Cust (in a fantastical rumour sometimes said to be Mrs Thatcher’s real grandfather) is ‘a crumpled rose-leaf, singed gnat’. The aged Dean of St Paul’s is ‘like a lion’s skin in a billiard room’. Writing like that lasts forever: and this wonderful, extensive selection is highly recommended. Duffy and Hyam have done a superb job in what is surely a labour of love. The footnotes are frequently a joy. One Master of St John’s was ‘a keen alpinist into his sixties, but so corpulent that his climbing companions refused to be roped to him in case his weight dragged them down a crevasse’. An Eton pupil, Sir Robert Filmer, ‘who succeeded to his baronetcy at the age of eight, fought at the Sudanese Battle of Omdurman on 2 September 1898. He died in France of wounds received while retrieving his pince-nez from a trench’.

Long acknowledged by archival explorers to be a great diarist, A.C. Benson has now been placed in the position where the rest of us can read him and concur. Silly as he was, and remote from commanding anything like agreement at any point, he enters the diarists’ pantheon for readers to shake their heads over in perpetuity.

Comments