After the turn-of the-century memoir Experience, Martin Amis’s career has been widely perceived as somewhat rocky, shading into moments of disaster. If Experience, with its triple narrative of father, teeth and Fred West, was regarded as a compelling and masterly whole, Amis’s subsequent novels and non-fiction have not been as widely admired.

Yellow Dog was quite a mess, getting some terrible reviews. The return to the knockabout vulgarian comedy that had made Amis’s name just lacked conviction. House of Meetings was more generally admired, being a fictional offshoot of a bizarre exercise, the non-fiction Koba the Dread. Both books were concerned with the crimes of Soviet Russia.

The Pregnant Widow divided readers. I have to say that I loved this romantic, funny tale of the sexual revolution taking place over a 1970s Italian summer, and the extended coda of the 40 years that followed. It married, for the first time in Amis’s work, broad and irresistible comedy with a sense of people who were warm, rounded and unpredictable; its rendering of the sad, short life of Amis’s alcoholic sister Sally was heartbreaking. At least I thought so. It is fair to say that other reviewers were more dismissive — it is sometimes difficult to explain a joke to the New York Times.

What seems stronger in Amis’s work in recent years is the humane tenderness for individuals. It is not brought in to prove a point against the prevailing grotesquery, like the angelic Kim Talent in London Fields. Rather, virtue is examined carefully, and often ascribed to women’s literacy and thought, as in Lucy Partington in Experience; long suffering, like Keith and his sister in The Pregnant Widow, is not the cause of laughter but of grave sympathy.

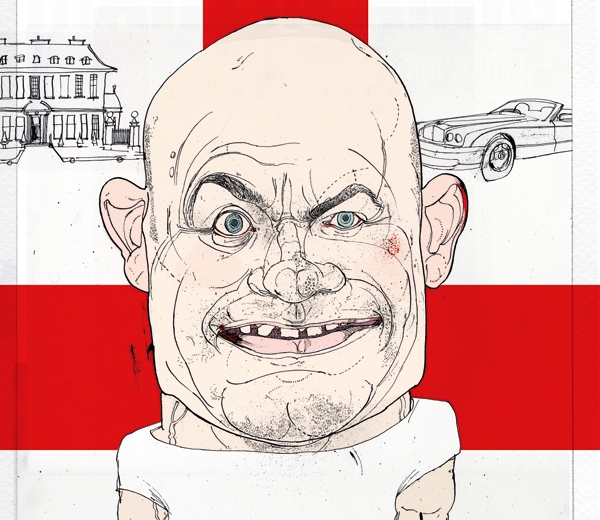

Some of the Quilp-like joy has gone out of the villains: compare John Self or Keith Talent with the mass-murderers of recent work, Koba or Fred West. The loss of zest for outbreaks of violence made Yellow Dog a painful, unfunny read. When one heard about the proposed subject matter of Lionel Asbo: State of England, sad to say, one immediately thought: ‘That’s what he can’t do any more.’

Yellow Dog failed, I think, because its subject was one of the slackest topics of the imagination: royalty. When our imaginative faculties are too weak to envisage anything else, we dream of princes. And Lionel Asbo is about something which engages our speculation in even more feeble moods. It’s very surprising to see Amis writing a novel about a yob who wins the national lottery. Lottery-winning is something which engages everyone’s fantasy life from time to time in weak ways. When we can’t imagine what it’s like to be a child, a foreigner, to live life in difficult circumstances or in complete obscurity, we still manage to send our minds out to think: ‘What would it be like if my numbers came up?’

Is it the job of the novelist to do what we can all do so well ourselves? Or would a better task for the novelist be to send his invention out into the lives of people consumed by futile longing — to explore not winners of the lottery, but people in love with the lottery? Amis has said that he based the main character and his girlfriend on the lottery-winner Michael Carroll and the glamour model Jordan. But how much more interesting it would have been to have written a novel about people who want to be this awful pair!

Lionel Asbo, a frightful thug with a complicated legal history and a more complex family one, wins a gigantic sum while in prison. His extended family, the Pepperdines (Lionel changed his name by deed poll), including brothers John, Paul, George, Ringo and Stuart, hover around hoping for handouts. The gene of intelligence runs unpredictably through the Pepperdines. The matriarch, Grace, a grandmother of teenagers before she’s 40 is a whiz at cryptic crosswords. In Lionel, the gene only manifests itself in ingenious evil. But the gift of intelligence alights on, and forms, Lionel’s nephew Des.

Amis’s concern is with the dignity of thought and the importance of intellectual improvement. Just as in his early novel, Success, the two central figures map opposing journeys. Lionel’s is into a hell of hatred and self-absorbed pleasure — the hotel waives his final drinks bill because they can’t believe it. His only connection with thought is his awful topless-model girlfriend who has ambitions to become famous through writing poetry. Des, less meteorically, moves into a modest, useful life which depends on nobody but his lovely, thoughtful wife Dawn and their baby, Cilla.

Dawn is escaping from a family of similar horror, including a racist, illiterate father: ‘He does sometimes go on about how they ruined his profession.’ ‘His profession? Ha — that’s a good one! Since when’s being a parking warden a…No. That’s unkind…’

Together, they will make a good life together, which includes reading, and is founded on love and respect. Amis punctuates their happiness with exclamation marks—‘In January, Dawn Sheringham fell pregnant!’ — as if signalling their constant surprise at the goodness of the world. The only problems are a terrible secret of Des’s (he, years earlier, once had sex with his grandmother Grace) and their ties with their appalling uncle Lionel. These are of duty, not money; but Lionel wants to impose duties of money instead. The plot, accurately described as a fairy story, unwinds in a clockwork way to a terrible conclusion, involving Lionel’s Tabasco-fed dogs, a door left deliberately open, and Des and Dawn’s baby, Cilla.

Lionel Asbo is a professional piece of work, verging on the expert — the detail of the plot, the characters’ crimes and ambitions and desires come together in a satisfying way. But it falls some way short of Amis’s best work, and, though it ought to be read is not essential Amis in the way that Money, Experience and The Pregnant Widow are. The best sections describe Lionel’s grotesque excesses as he moves into a luxury hotel and starts throwing his money at barmen while acquiring a crowd of yes-men and PR advisers: ‘Now Lionel. No one wants to see a multimillionaire with a scowl on his face.’

The Timon-like dinner where Lionel throws his brothers’ hopes back in their faces is first-rate. And the sequence in which he succeeds in placing his mother Grace in a home for the elderly in the remotest north of Scotland has some of the old brio:

How’d she take it? Oh, you know. On come the waterworks. I’ll miss me sister! All this. I said: Woman, you forty-two. You can’t fight the march of time! She’ll love it when she’s there.

But there’s a disappointing lack of energy elsewhere, and a loss of control over the details of Lionel’s life. Would he, in 2012, really call out for Savile Row tailors? Wouldn’t someone like him go immediately to Gucci in Sloane Street to buy off-the-peg fashion suits?

The lottery, as I said, is a weak central device, because one has gone over it so often oneself. Lionel’s malice is entertainingly handled, and works itself out in pleasingly horrible ways. But as a character he is not illuminatingly done. It is a sign of laziness when his appearance is compared to Wayne Rooney’s.

When I heard that Amis was writing a novel about a lottery-winning lout and his terrible glamour girlfriend, I had severe doubts. But all in all, it is not as bad as I feared.

Comments