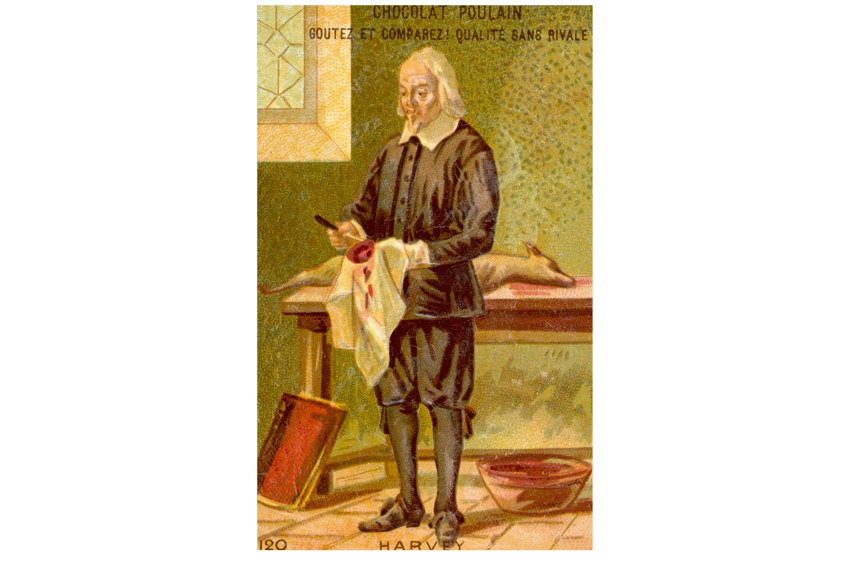

Everybody knows that the heart pumps blood around the body, and that a man called William Harvey somehow discovered this fact. Before Harvey, people thought that blood moved around the body in a sluggish fashion. But then Harvey — who was born 14 years after Shakespeare — noticed that, actually, blood shoots out of the heart with great force, travels through the arteries, and then makes its way back to the heart through the veins. To find this out, in an age before X-rays, sonograms or heart monitors, you would, if you think about it, have had to be a pretty gruesome sort of person.

As soon as I started this book, I was gripped with a curiosity I should, I realised, have had all along. How did Harvey make his discovery? I had to wait until about halfway through the book to find out. Meanwhile Thomas Wright, a decent biographer, got me acquainted with Harvey — who, after Newton, Darwin, Einstein and Galileo, is one of the most important scientists who ever lived. Born in Kent in 1578, he had six brothers and two sisters. His father was a pushy sheep farmer, desperate for social recognition. William was extremely bright, so he was sent to the King’s School, Canterbury, where he toiled away at the classics.

At 16, he was accepted into Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge, where he lived the spartan life of the commoner, sleeping in a cramped attic, waking at 4 a.m. and grinding away at Latin and Greek texts for up to 18 hours a day. It is thought that he speed-read standing up, and lived on porridge and cheap cuts of meat. He was fiery and driven. After a year, he won a scholarship.

When he graduated, he went to study medicine in Padua, then the top medical school in the world. He revered Galen, the Greek doctor whose theories he would eventually overturn. We get a picture of a young, ambitious man, with slightly mad eyes, walking to lectures through the narrow medieval streets, his hand never far from the dagger he had taken to wearing, just in case.

One place in Padua that influenced Harvey hugely was the anatomy theatre. Imagine an opera house, but tiny, with stacked galleries, rammed with spectators. The celebrity anatomist, Fabricius (real name Girolamo Fabrizi, a nasty piece of work) appears in his purple robes with gold trim. Lute music announces the arrival of the corpse, which rises from the floor, as if by magic. Fabricius has arranged for the flesh to be pre-cut, for better showmanship. Then he takes the body apart with tremendous panache. He cuts and yanks and reveals; the audience adore him. The young Harvey is lapping it up. This, he sees, is what he wants to do.

What a player he was, too! Back in England, he married Elizabeth, the daughter of an influential doctor, Lancelot Browne. Through his social-climbing brother, he oiled his way into the court of James I, becoming the King’s ‘physician ordinary’, on a salary of £300 a year. He speculated in property. He had a house in Ludgate Circus, in the centre of London. In this house, he had a special room for the purposes of research. This is where the story gets gruesome. In this room, he kept ‘toads, crabs, shrimps, whelks, oysters and fish’, and also ‘lizards, tortoises, serpents, fowls, pigeons, geese, rabbits and mice scurrying around or lying lazily in cages or hutches’. When he got home in the evening, he liked to cut these creatures up.

That’s how this mad-eyed, brilliant, fanatical person found out about the circulation of the blood. He cut animals up, day after day, for years on end, and studied their hearts. One imagines him bustling home, pecking his wife on the cheek, and racing into his study, gratefully taking in the aroma of his doomed menagerie. There’s a detailed description of Harvey cutting out an eel’s heart and dissecting the still-throbbing piece of flesh. There’s another description of Harvey tying live dogs to his table, opening their chests, and fiddling about with their hearts — tying off vessels, or slicing into the actual heart. We also watch as he cuts into the heart of a dead man he has managed to procure.

Basically, he made his discovery by cutting into a living dog’s heart, and watching the blood spurt out, until the dog died. All that blood had to go somewhere, he reasoned, otherwise the dog would explode. The only explanation was that it was the same blood, going round and round.

Of course, lots of people didn’t believe him. He used to demonstrate his theory, using dogs, every so often. Then came the Civil War. Harvey, as a royal retainer, was forced to live outside London. His papers were destroyed. His wife died. They never had any children. He developed gout. Later in life, it is said, he paid a young lady to sleep with him ‘for warmeth sake’.

He bequeathed thousands of pounds to the College of Physicians, who built a statue in his memory. The statue was destroyed in the fire of London. But he needn’t have worried. We still remember him, in a vague sort of way, as the man who, somehow or other, discovered the circulation of the blood.

Comments