In my study at home stands a small cork board with the names of eight target schools for my ten-year-old son. The state schools are on the left, the private schools on the right. The decision is due soon and I still have no idea what to do.

There aren’t many things that Britain genuinely does better than anyone else in the world, but secondary education is one of them. The discerning Russian plutocrat, who could buy anything anywhere, would have his son in England for his teenage years followed by an American Ivy League university. International league tables rank our private schools top of the world — their quality is world famous. But what’s less well-known is that exam results in the best state schools are now just as good. Which, given that they get by on less than a third of the money, is quite striking.

Over the past year, as a parent, I’ve been plunged into the great maze of English secondary education. As a Scot, it’s entirely new to me. I went to my local primary in the Highlands followed by my local comprehensive: no tests, no choice, no worries. When my dad was posted to Cyprus with the RAF, I boarded for five years with the military covering my fees. So having seen upsides and downsides of both the state and private system, I now have to choose for my children. As I’ve looked at and around all kinds of schools, I’ve discovered just how out-of-date my assumptions were.

Take the idea that private schools always perform better than government ones: for many years, that was true. Let’s look at Cambridge University’s admission statistics. Before the war, only about 20 per cent of its undergraduates came from state schools. When I started school in the mid-1980s it was 40 per cent. Now it’s 60 per cent and rising. Oxford is following the same trend. Why? Not because either university excels at social outreach: their intake follows a massive shift in exam attainment. Consider the cohort of students who score AAA (or better) at A-level. When I was sitting these exams in the early 1990s, just 57 per cent of them were in state school. Now it’s 70 per cent.

The best state schools tend to be grammars, which are notoriously cash-strapped. They now get around £4,500 per pupil each year, lower than the £5,200 national average and dwarfed by the £17,000 private school average. It seems to be a mystery: where’s the link between cash and attainment? It’s a question politicians ask too. The state school system has notoriously wide variety in per-pupil funding: from £4,500 (Somerset) to £8,000 (Tower Hamlets) depending on the funding formula. But pupils in poorer-funded schools don’t get lower grades.

When Nick Clegg wanted to push through a ‘pupil premium’, whereby children from deprived homes would bring more cash with them to their schools, he needed proof that the idea would work. Having gone to the elite Westminster School, it would have seemed natural to him to assume that money buys a better education. The accountancy firm Deloitte was commissioned to run a massive study, but it found no relationship between attainment and per-pupil funding. In other words, there’s absolutely nothing to suggest that Clegg’s ‘pupil premium’ would make a blind bit of difference. The Deloitte report was buried and the policy rolled out anyway.

That was eight years ago. Since then, we have Michael Gove’s more demanding curriculum being taught by teachers getting by on less money. I’ve been struck, in the course of school visits, to hear from teachers how funding cuts are threatening progress. Head teachers at grammars complain about staff being poached, with their resources threadbare. The best girls’ grammar, Henrietta Barnett School in London, is dropping A-level subjects. Another star performer, St Joseph’s College in Stoke-on-Trent, is cutting ten staff.

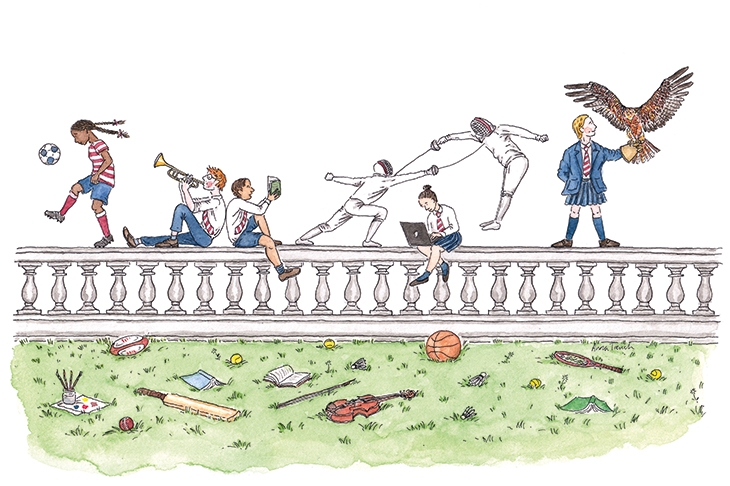

Needless to say, there are no signs of financial strain on private schools whose fees move ever upwards. Out of pure voyeurism I went to the open day at St Paul’s in London, arguably one of the best schools in the world. ‘Of course, our pupils get excellent grades, we have our pick of the brightest,’ said its headmaster. Parents were paying, he said, for children to be stretched not just by the national curriculum but in sports, culture, debate, trips, interests and passions. (Some of the boys there had started a knitting club.) St Paul’s certainly believes in a link between cash and teaching quality: it boasts how, each year, it reviews teachers’ salaries across Britain to make sure it pays the most.

A friend of mine who teaches in a grammar has a theory. Religious schools tend to do well, he says, because they focus on character-building first and academics second: ethos before logos. The private schools also do a secular version of this, which is why they’re effective. He believes the weakness of grammars is that they conform to the cliché of being exam hothouses teaching to the test, but not beyond. He’s quite gloomy about grammars, fearing they’re losing their competitive edge with cuts forcing them to narrow their scope and ambition. He now has so many classes that he teaches 400 boys: a figure, he says, that makes it impossible to get to know the pupils.

It’s certainly true that private schools sell themselves on the extras: the quality of the music and drama, how they pick up pupils who fall behind. Which isn’t something that grammars seem to specialise in. I was shocked to find that pupils who struggle with their GCSEs in grammars can be expelled, lest they go on to sully its average A-level score. This practice is called being ‘kicked’ which, to me, sounds like it ought to be illegal. This underlines the concern that the super-gifted would prosper in a grammar but a child who needs the extra attention is unlikely to get it. So the differences between the best state and private schools can’t be spotted in an A-level league table. This makes it harder to work out where the added value lies — and whether you might be able to apply it yourself with less me-time and more parenting. Or, perhaps, go private at a later date.

When my Swedish wife describes Britain to her friends, she sometimes says that young people who don’t have children worry about where their as-yet-unconceived children will go to school. Swedes find it hilarious. Perhaps it is. The bottom line is that if you’re lucky enough to live in a leafy area, the school options — state and private — will be pretty good. So choosing will be difficult. But it’s a nice problem to have

Comments