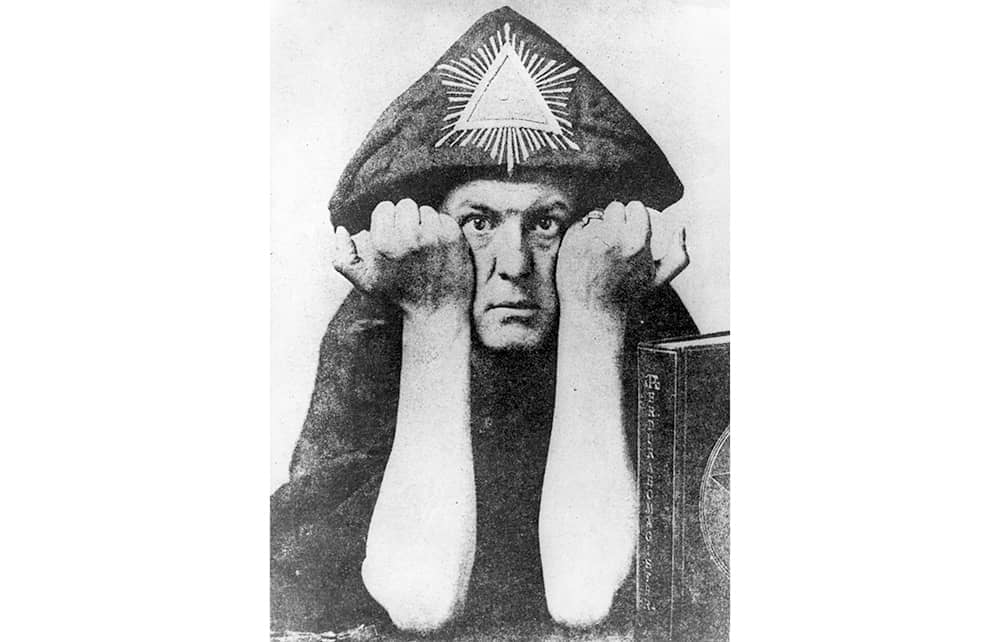

I have never had much time for Aleister Crowley. Magic(k) is nonsense; the mystical societies he founded were simply pretexts for him to take as many drugs and have as much sex as he could. And he was a second-rate writer at best. When the novelist Arthur Calder-Marshall said he had gone ‘from Great Beast to Great Bore’, I thought it a fair summing-up. Crowley initiates were some of the dodgiest people in the western world – either frauds or hucksters themselves or the most gullible of fools.

There was always the matter of his self-reinvention. Aleister Crowley was not christened thus: he changed his first name because he thought that a dactyl followed by a spondee conferred the greatest chance of becoming famous. (I cannot say it has done me any favours.) And yet a powerful magus does not end his days in Hastings. (Sorry, Hastings.) So even though Crowley exerts a pull to this day, and not only on the credulous, I had only a mild curiosity about this book to start with.

I am not sure my expectations have ever been so out of joint with the reality. Dipping at random, I found this, under the entry for ‘Café Royal, Regent Street’: ‘On another occasion Crowley is alleged to have entertained a party of guests royally, excused himself to go to the gents, and absconded down Regent Street in a taxi, dodging the bill.’

It’s all fun and games, just about, until we get to page 109 and his encounter with Leah Hirsig

Leave aside that, as I read more of the book, it became clear that this was pretty much the archetypal Crowley story, confirming, in a sentence, at least one of the misgivings I had about the man – of course he would do that – but look at the word ‘alleged’. Crowley has been dead for seven and a half decades: he is not going to sue. But Phil Baker is a scrupulous writer, and if he can’t get chapter and verse on an incident he’s not going to pretend he has.

Anyway, Crowley provided us with enough material for most of Baker’s work to consist of reporting verified fact (along with a useful and well-judged commentary). And here’s what Crowley could come up with – ‘The Most Holy, Most Illustrious, Most Illuminated and Most Puissant Baphomet, X degree, Rex Summus Sanctissimus 33 degree, 90 degree, 96 degree, Past Grand Master of the United States of America, Grand Master of Ireland, Iona’ – and you can only speculate on how anyone could believe that these self-proclaimed titles meant anything, even if Crowley himself did.

In the end I don’t think it matters. There was plenty of this stuff around at the time. W.B. Yeats (who hated Crowley) was mixed up in it too; a hodge-podge of half-baked, pseudo-religious imagery and bad Latin which Crowley used in order to find sexual partners and pay for his drug habit – cocaine and heroin mainly. The fine dining can’t have been cheap either, but to Crowley’s credit he had a knack of being paid for by whoever he was with at the time, when he wasn’t (allegedly) doing a runner from the restaurant itself.

His London was largely centred on an area encompassing the western end of Piccadilly and Soho. There were offshoots in Fulham and Hampstead, but this was his preferred stamping ground. He was something of a gourmet and particularly fond of exotic foods such as Chinese or curry; but he was equally happy with oysters and lobsters, and who isn’t? These details humanise him; they declaw the Beast. I was particularly touched that he often ate at Chez Victor, as did I; in fact, I wooed my wife-to-be there. If there is one thing to mourn above all that has gone from London it is the good restaurant that you can actually afford.

So what we have here is a portrait of London from the early 20th century to the 1940s, with gaps occurring during the intervals Crowley lived abroad (in the USA during the first world war, or Cefalù, in Sicily, in the 1920s). Much of that world has vanished, but there are still traces; and in some instances (the French House and the Dog and Duck in Soho) the places are unchanged, more or less.

It is all fun and games, just about, until we get to page 109 and his encounter with Leah Hirsig (‘Alostrael’). I shall spare you the details of what he got up to, or claimed to have got up to, with her. Suffice it to say that Baker makes this comment: ‘Trying to have sex with a goat (after which Crowley cut its throat) seems innocuous enough’ by comparison. ‘It doesn’t sound either allegorical or pure fantasy,’ he adds, of Crowley’s account.

Do we stray from the fantasy world of the Marquis de Sade into the real one? Did this abominable thing (it involves children) happen? Baker says it probably did, and I trust his opinion. And this is the true value of the book: it turns the ridiculous into something darker and stranger.

Comments