The relationship entertained by French elites to their homeland is very different from their English counterparts. ‘England is perhaps the only great country whose intellectuals are ashamed of their own nationality’, wrote George Orwell in 1945. That derisory sentiment continues today among Britain’s urban elites.

French elites by contrast – though they can be highly critical of their country among themselves – do not shy from exalting its status abroad. French nationalism, born of the French Revolution, only came to be embraced by the right a century later. From then onwards, basic patriotism crosses political boundaries.

While Britain’s position is not rosy, France’s is certainly no better

Elite francofilia has long been a facet of English snobbery. Orwell refers to the Catholic author GK Chesterton’s ‘romanticised’ vision of France ‘as a land of Catholic peasants incessantly singing the Marseillaise over glasses of red wine.’ No harm in that – until that romanticism was extended to an ‘enormous over-estimation of French military power’ after the First World War. Orwell concluded ‘that had the romantic rubbish which [Chesterton] habitually wrote about France and the French army been written by somebody else about Britain and the British army, he would have been the first to jeer.’

Listening to the BBC these days and switching over to French public radio the contrast is striking. One is a constant depressive dirge on the UK’s woes; the other critically analytical of France’s problems, but upbeat in tone. Yet one might expect the reverse.

Take one raw statistic. In 2021, both World Bank and United Nations GDP (nominal) rankings have the UK at 5th and France 7th. International Monetary Fund estimates for 2022 show India overtaking the UK to claim the 5th spot for world GDP, but with France still 7th.

One may question the reliability of GDP as a comparator, but a host of other measures regularly show France worse off than the UK. Debt to GDP ratios show France at some 115 per cent, the UK 99.6 per cent. Meanwhile the Bank for International Settlements gives France’s total public and private debt (non-financial) at 351 per cent; the UK at 271 per cent.

One can rightly point to France’s present day lower inflation at 7.1 per cent (EU harmonised) compared to the UK’s 10.7 per cent. But as French debt statistics above show, president Emmanuel Macron began forcing down domestic inflation by subsidising prices during his 2022 presidential election campaign. French unemployment at 7.4 per cent compares unfavourably with the UK’s 3.4 per cent. Meanwhile France is the highest taxed OECD and EU state, leaving little margin for manoeuvre. Her balance of payments figures are as gloomy as the UK’s, together with her flat economic growth.

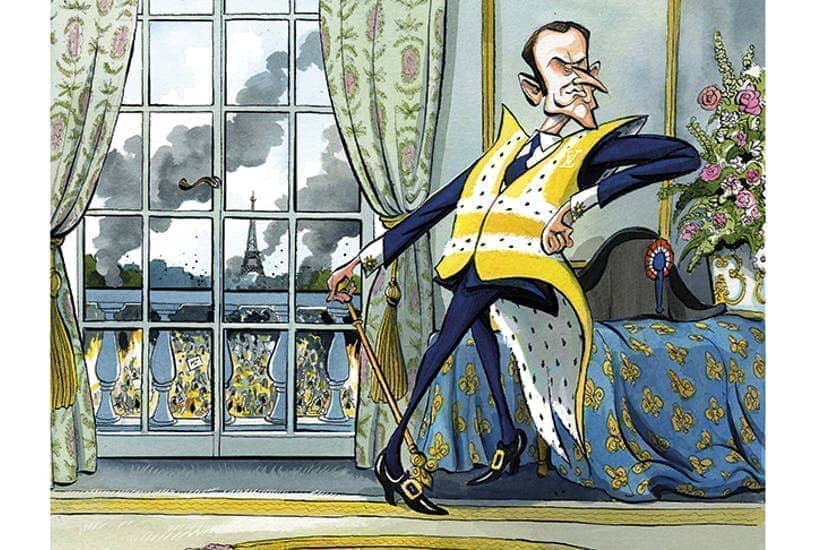

While Britain’s position is not rosy, France’s is certainly no better. That is why recent predictions in a certain European press, not least in France, taken up by British elites, that the UK was descending into terminal decline has lost all proportion. If the French press enjoy a touch of schadenfreude at the expense of the old enemy, and French politicians are glad to distract from their own problems, the willingness of much of the British middle class to swallow the same view can only be explained by ingrained cultural habit aggravated by post-Brexit resentment. Today, with Macron utterly wedded to the EU project, France for British elites is ipso facto superior to Britain. Yet France’s moral state is parlous.

Since the 2022 presidential and legislative elections Macron’s centrist party has no overall majority. France is stalemated and drifting towards ever more radical politics. Macron’s prime minister Élisabeth Borne, unable to command a majority in the National Assembly, struggles to get her business other than by the constitutional sleight of hand of article 49,3, which guillotines parliamentary debate. With the chamber split four ways the question remains as to whether Macron will eventually dissolve parliament. Opinion polls suggest this would be a gift to Marine Le Pen’s party, already the single largest opposition party with 89 seats. France might then come to replicate the present radical right Italian government.

Socially and culturally French society is far from healthy. Other than worsening violence and lawlessness in the banlieues – conveniently out of sight of English elites’ visits to France – the French model of assimilation and laïcité is being tested to destruction. Official Justice Ministry statistics for July 2021 show 24.6 per cent of the prison population as foreign (double the proportion in Britain). The French Interior Minister publicly stated this summer that although foreigners make up 7.4 per cent of the French population they account for 19 per cent of all delinquency nationally, and that 48 per cent of arrested delinquents in Paris are foreigners, 55 per cent in Marseille, 39 per cent in Lyon.

Meanwhile, hostility to France’s headscarf ban, and the prospect of it being extended, provokes growing resentment and at least passive defiance towards laïcité and the Republic from elements of France’s Muslim community. The general picture is of a France far from at ease with itself. The prospect of a member of France’s ethnic minorities leading the country with no fuss in the near future, as has just happened in Britain, seems impossible. Indeed, France’s best-selling novelist, Michel Houellebecq – tipped for the Nobel literature prize this year – in 2015 penned just such a scenario to a mixture of national apprehension and anxiety.

Sections of the British elite have long deprecated their country. In the 1930s, Orwell castigated the English intellectual for his ‘mechanical anti-British attitude’. But he suggested a remedy:

‘The Bloomsbury highbrow, with his mechanical snigger, is as out-of-date as the cavalry colonel. A modern nation cannot afford either of them. Patriotism and intelligence will have to come together again.’

If they are to succeed in this – as the leadership of the Labour party now seems to hope – left-wing British elites would do no better than to look to their French counterparts, who manage to combine criticism of their country’s failings with a commitment to its success and defence of its fundamental values.

Comments