Some years ago I went to a dinner party in Lucknow, capital of India’s Uttar Pradesh, where the hosts and their guests were Hindus who as children had fled Lahore in 1947 at the time of Partition. A week later I was in Lahore, capital of Pakistan’s Punjab, and found myself in a house where the other diners were Muslim refugees who at a similar age had come from Lucknow. Midway through the second meal, I suddenly realised how similar the two groups of middle-class professional people were. Lawyers, teachers, booksellers and architects, they shared the same tastes and the same worries, their chief anxiety being that their belligerent governments had both recently acquired nuclear weapons. The dinner parties might have been interchangeable, but for the whisky in Lucknow and the orange juice in Lahore.

As my friends talked of the tragedy of partition, I wondered at its futility. Did not these groups demonstrate that it had been unnecessary as well as tragic because they were essentially the same people, Indians who happened to have different faiths? Only afterwards did I realise that this was an illusion, that I had simply come across one of those increasingly rare intersections of Indian and Pakistani life. Those Hindus in Lucknow had nothing in common with their militant co-religionists who had destroyed a mosque on the grounds that the god Ram had been born on its site and who in 2002 massacred thousands of Muslims in Gujarat. Nor did the Muslim advocates I met in Lahore share much beyond their profession with the lawyers who earlier this month applauded murder and garlanded the assassin of Salmaan Taseer, the governor of the Punjab who was killed because he had criticised the blasphemy laws of Pakistan.

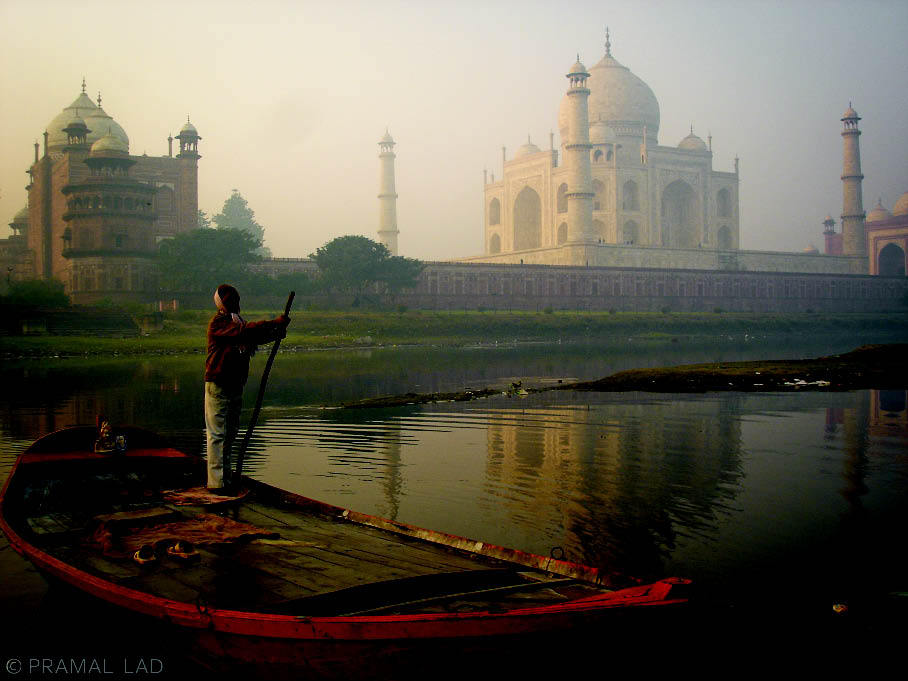

India is a land of contrasts and illusions (and often of clichés). As Patrick French notes in the introduction of his admirable new book, ‘everyone has a reaction to India … They hate it or love it, think it mystical or profane; find it extravagant or ascetic; consider the food the best or the worst in the world.’ Yet the contrasts do not exist simply in the minds and emotions of visitors: they are often unbearably real, as real as they are in any country in the world. India is regularly hailed as one of the economic powers of the future, possessing more dollar billionaires than Britain, but hundreds of millions of its people still live in poverty, working for a dollar or two each day. The economy may be growing at a rate of more than 7 per cent a year, but over the last decade nearly 200,000 farmers have committed suicide, often by swallowing a tin of pesticide, because they can no longer make a living from their land.

There are many Indias, and Patrick French sets out, with enthusiasm and empathy, to encounter as many as he can find. He is an observant traveller with a taste for the unusual and the idiosyncratic. He describes the ear-cleaners of Delhi at their work; he assists the dabbawallas of Mumbai, who daily deliver 200,000 cooked tiffins in stacked metal containers by handcart; he meets a wine-grower who has made a success of his trade in a country where the annual per capita consumption of wine would not fill a tablespoon. He is always alive to nuances of caste and faith and custom. One Tamil Brahmin tells him how she uses a different vocabulary with non-Brahmins and how people of her caste even tie their saris differently.

Like V.S. Naipaul, of whom he has written a brilliant biography, French travels to uninviting places to meet unpalatable people such as gay pimps, Kashmiri terrorists and politicians in jail. He even goes to the forests of Andhra Pradesh to interview maoist guerrillas who control 40,000 square kilometres of Indian territory. Although maoism is dead everywhere else, he finds these people unrepentant, convinced that their struggle is just and their philosophy correct. Last April they murdered 82 police constables in an ambush.

The author is a veteran of India’s elections and spends a great deal of his time attending rallies and interviewing candidates. A good listener as well as a good writer, he tries to remain as open-minded as possible, but even he is sometimes flummoxed by the views of politicians. Between 1998 and 2004 India’s government was dominated by the right-wing BJP, the Hindu nationalist party that aspired to overtake Congress as the natural party of government. Yet for all its self-proclaimed modernity and understanding of business, much of the party’s message was narrow, backward and ludicrous. French tries hard to understand Hindu nationalism but every time comes up ‘against the irrational’, people who believe in ‘the rule of Lord Ram’, people whose principal policy is cow protection, one person who even claimed that ancient India had aeroplanes.

This irrationalism, coupled with the desire to take revenge on modern Muslims for the medieval invasions of their ancestors, contributed to the unexpected defeat of the BJP in 2004. Since then India has been intelligently guided by Sonia Gandhi and the remarkable Manmohan Singh, who as finance minister opened up the economy and who as prime minister has proved to be India’s wisest statesman since Nehru. Unusually in the post-colonial world, Manmohan Singh has also had the courage to recognise that ‘India’s experience with Britain had its beneficial consequences’ and that his country’s ‘notions of the rule of law, of a constitutional government, of a free press [and] of a professional civil service’ had been ‘fashioned in the crucible where an age-old civilisation met the dominant empire of the day’.

French is a quirky writer who erects a formal structure for his book and then subverts it whenever he feels like taking a diversion. Readers will happily accompany him on his travels and encounters across a land of such colour and unexpectedness, though they may find some of his political interspersions less interesting: his passages on Sanjay, Indira and other Gandhis do not contain much that is unfamiliar. One of the highlights of the book is a fascinating piece of political and sociological research done with the aid of computers, spreadsheets and assistants. French suddenly became inspired to look at the backgrounds of all the MPs in the Delhi parliament to see how they had become politicians, and in the process he discovered that politics in India are becoming less and less meritocratic and more and more a hereditary profession. The entire younger generation of Congress MPs now consists of people who have in one way or another inherited their seats. Indian democracy is an enduring and indeed massive achievement, but it has some way to go before it becomes representative.

Comments