The principal purpose of Captain James Cook’s last voyage, which began in Plymouth on 12 July 1776, was to discover the elusive Northwest Passage. Attempts had been made before, in vain, from the Atlantic, but this time it would be from the west, from the Pacific.

On the way, Cook was to return an Anglicised Polynesian named Mai to Raiatea, ‘a ragged volcanic island’ about 130 miles north west of Tahiti. Mai takes up much of Hampton Sides’s narrative, offering ‘a poignant allegory of first contact’, before being deposited home with his cargo of English domestic farm animals and his suits.

Prior to that, Cook had investigated, in New Zealand, the massacre of ten crew members of the Adventure, the Resolution’s sister ship on his previous voyage. His attitude to this tells us much about him. He was neither vengeful nor judgmental. One of his powering characteristics was a profound curiosity. He wanted to know what had happened. In the event, he decided that the Maoris had been provoked. Despite the victims having been eaten, Cook knew anthropophagy was a Maori warrior ritual. The custom, he wrote, has ‘undoubtedly been handed down to them from the earliest times’. He saw no reason to impose Christian morality or English ethics.

Cook’s moods on this third voyage were regarded by those who knew him as more friable than before. He lost his temper easily and had crew members thrashed frequently for minor misdemeanours. Errors of judgment crept in where once he had always seemed right. Explanations for his caprices have ranged from a parasitic infection after eating bad fish to sciatica and consequent opioid addiction, and vitamin B deficiency. Or he may just have been getting old and crotchety, having spent so much of his life at sea.

The Maoris found Cook lacking in the principle of utu, which required him to exact revenge for the killing of his men. His refusal to do so was taken as a sign of weakness. A later, progressive historian regarded Cook’s leniency as a ‘trait of authoritarianism’. Sometimes there’s no winning. Sides detects a further change in Cook after this visit when he wrote of the Maoris:

We debauch their morals and we introduce among them wants and diseases which they never before knew… [serving] only to disturb that tranquillity they and their forefathers enjoyed.

It nonetheless remained the case that what gave Cook most pleasure was the observation of newly contacted indigenous peoples. Anthropology, in other words. He was fascinated by the Tasman aborigines, the Palawa, who lived by the sea but did not swim or eat fish and had no boats. By contrast, he was astounded by the expert seamanship of people so far distant from one another as the Hawaiians and the Maoris, who spoke the same language.

During his second voyage, Cook had proclaimed that he wanted to go not only ‘farther than any man has been before me… but also as far as I think it possible for man to go’. Two centuries later, Gene Roddenberry split that final infinitive with the adverb ‘boldly’, and Captain James T. Kirk was on his way ‘to explore strange new worlds’.

Cook liked to stride ashore to such strange new places alone and unarmed. Sides writes:

It was a kind of theatre of first contact. On one level, it involved a bravery and a confidence that bordered on recklessness. Behind it, though, was an optimism. He believed cultures could be made to understand one another: if he used the right tone and body language, if he looked them in the eye and showed proper respect, the chasm between radically different peoples could be bridged.

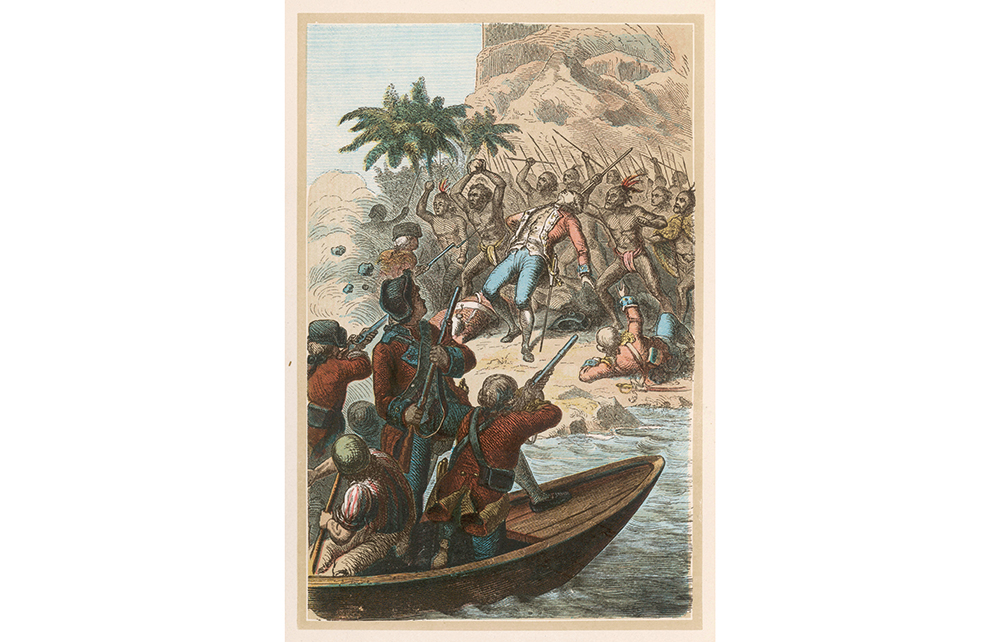

Famously, it didn’t always work. Cook was clubbed to death on the beach at Kealakakua on the island of Hawaii. He had been incensed by the theft, for its iron parts, of the largest boat he had, a cutter, an ‘indispensable workhorse which in certain situations could spell the difference between life and death for his crew’. He hatched a plan to kidnap the local king, whom he would then swap for his boat. It went wrong. Be not too bold.

In the past few decades, Cook has been seen as the symbolic villain of European colonialism in the Pacific. Judging from this book, his critics have very much got the wrong man. It is difficult to imagine progressive voices now tolerating the patriarchy, cannibalism, human sacrifice and internecine violence that Cook observed and refused to condemn or interfere with. He was as broad-minded a man as could possibly be imagined in the 18th century. He also happened to be an exceptional mariner and a cartographer of genius.

Sides has written a riveting book, deeply researched, light of touch and always judicious and full-sailed about an exceptional man’s final extraordinary journey.

Comments