At the end of each year I pull out most of the New Year’s resolutions I’ve ever made — I now have them going back nearly two decades. They make for curious reading: some years they seem less like an account of what I intend to do with my life than what I don’t. I never took voice lessons, or wrote an original song for the guitar given to me six years ago by my wife, or even learned how to play that guitar. I never learned Spanish, or how to cook. I didn’t write that book about Obama, or create a television drama about Wall Street, or swim a 50-metre sprint in under 30 seconds, or ‘perform one act of charity each month big enough that it hurts at least a little bit to do it’.

After reading the lists of ways I’ve failed to improve myself, and things I’ve failed to accomplish, I set out to make the next year’s list. Part of me genuinely wants to believe that this year will be different. The other part of me thinks: so what if it isn’t? Unkept promises have their own power. They’re like sloppy travel plans: you may not end up going where you’d intended, but if you hadn’t planned the trip you wouldn’t have gone anywhere at all. Years ago I sold my publisher two books about American baseball. The first book was to be called Moneyball, the second, a sequel, Underdogs. Moneyball was a story about how markets can value people so irrationally that they can misvalue even professional athletes. It got written so quickly I didn’t have time to make a resolution about it. It doesn’t matter what the sequel was about but for the next five years it was a New Year’s resolution. Reading over my old resolutions at the end of the fifth year, I realised that the book shouldn’t be a sequel but a prequel, about the psychologists who had uncovered the irrationality in the human mind that had made Moneyball possible. I’ve just written that book, The Undoing Project, in response to an unfulfilled resolution.

The unfulfilled resolution that leaps off the page this year dates back to 2016: Teach My Children About Money. The ambition came to me in a funny way, after a friend called me to tell me that his wealthy mother had died, and left behind a financial mystery. She’d grown up in Germany in the 1930s, in an affluent Jewish family. After Hitler came to power she and her parents had fled, eventually to the United States, but had lost pretty much everything except their lives. In America she married another Jewish refugee and together they had rebuilt their fortunes. And yet she never lost her sense that civilisation was always just a tiny jolt from total collapse. As she moved from American home to ever-larger American home, she carried with her wherever she went the same lead box filled with gold coins, which she buried in her garden. Her final garden had been a six-acre tract outside New York City, and she’d died without telling anyone where in it she had buried her gold. She’d paid roughly $60,000 for it back in the 1960s. It was now worth more than two million.

My children’s reaction to the situation had surprised me. First was their disinterest. None of them could understand why anyone would bury a box of gold: why not just put the money in a bank? My eight-year-old son couldn’t get his mind around why anyone would buy gold in the first place. ‘I don’t understand why gold is precious,’ he’d said, for example. ‘Why isn’t bronze precious?’ He had all sorts of strange ideas about money: where it came from, how you got it, who made it and who didn’t. ‘There are so many jobs and in every single job you can make enough money,’ he explained to me at one point. ‘Except one. Public school teachers. Because kids don’t pay to go to public school, the teachers don’t get paid to teach there.’

It’s actually harder than it needs to be to teach my children about anything: the mere fact that the information comes from me discredits it. Still, I’d hatched that resolution: Teach My Children About Money. There’s this huge gap in the American educational system. Our society is more obsessed, disturbed and confused than any that ever existed about financial matters. Yet we don’t bother to teach children how to think about them. I’d start with my son, I decided, and use my friend’s buried treasure as a MacGuffin. I actually went so far as to buy work gloves, shovels and a pair of state-of-the-art metal detectors, and have them shipped to a Soho hotel. Digging for two million dollars of gold would get his attention, I assumed, at least for long enough for me get him to listen to what I had to say about money: how the possession of large sums leads people to think and act strangely; how bizarre it can be who turns out to get his hands on a lot of it and who does not; how it is as often ‘found’ as it is ‘earned’. Some other things, too.

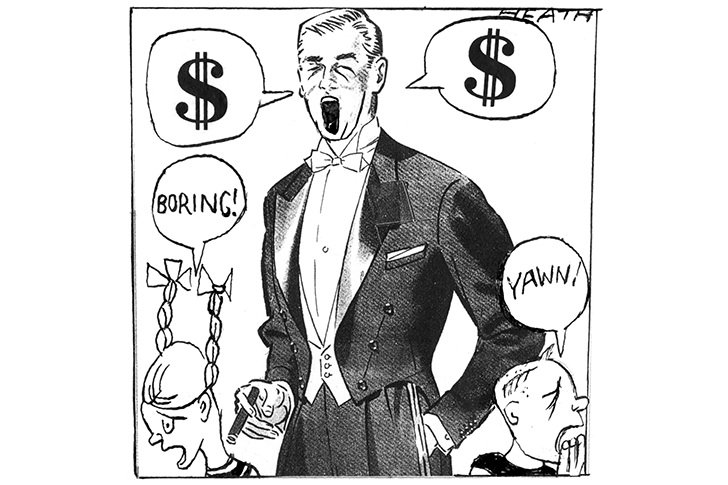

We flew to New York City and drove to my friend’s mother’s house, and began to dig where the metal detectors told us to dig. We found a great many things, none of them gold. ‘She had a robot dog that pooped metal,’ my son concluded. But after an hour or so he entirely lost interest — in the gold, in money, in listening to me. Most of what happened that day is a story for another time. My friend never found his mother’s gold and I never taught my children about money. But this old resolution is maybe about to take on new life. For just now my children are sensing the power of money. They see its effects every day, in their money-drunk President, and his money-drunk friends, who behave in ways no child would approve of. Their civilisation feels as if it is just a tiny jolt away from total collapse. They may be ready to learn why.

Comments