As an early dedicated fan of the Doors, who ran away from boarding school just so that I could catch my idols playing the massive Isle of Wight festival (a gathering of the Hippie tribes that in retrospect marked the end of the peace ‘n love era) I approached this book with more than casual interest.

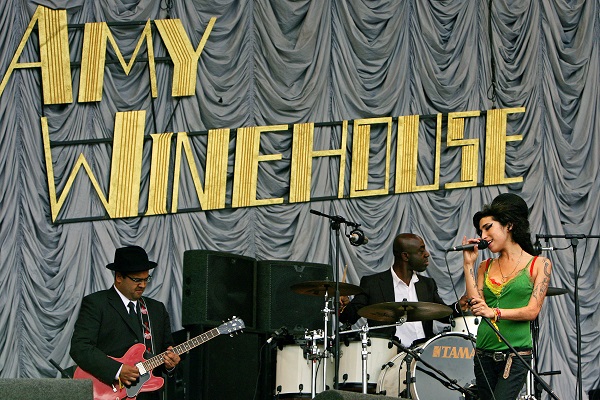

I saw and heard two of its subjects – Jimi Hendrix and my hero Jim Morrison – give what turned out to be their swansongs that sweaty August night on the island. Both were dead within the year. Both were aged 27, as were rock biographer Howard Sounes’s other subjects: Brian Jones of the Rolling Stones in 1969; Janis Joplin in 1970; Kurt Cobain in 1994, and most recently Amy Winehouse in 2011.

A besotted admirer of the hugely talented but equally self-destructive Winehouse (was ever a star more aptly named?), Sounes at first contemplated a full-scale life of his rock goddess, but realised, as he freely admits, that her all too brief blaze across the musical firmament offered thin pickings for a big biography.

He therefore decided to pad things out by writing a comparative study of Amy and five other rock stars who, like her, played their last gigs, shot up their final fixes and drained their parting bottles at the age of 27. But was this calendar coincidence of their death dates any more than that?

Sounes is not the first person to have noticed that these dark stars all flickered out at the same age. In fact, the phenomenon has acquired a collective name: the 27 Club. Sounes’ s book includes an Appendix listing around 50 other musicians and singers who departed at that age – though none, it must be said, are half as (in)famous as his six principal subjects.

As well as the age at which they died, the other elements common to all six are abuse of drink and/or drugs; dysfunctional relationships with family, lovers, friends and fellow musicians; physical and/or mental health ‘issues’; disillusion with the music industry which made their names and fortunes; and, of course, the unnatural way in which they all met their ends. By the book’s end, however erroneously, we begin to think that death by drink and drugs is the rock industry’s own way of delivering death by natural causes.

Amy Winehouse was quite typical of the 27 Club. Her parents split up when she was a child, although both continued to be in contact with her. Indeed, her London cabbie father, Mitch, tried to build a career as a cabaret star on the back of his daughter’s success, and her MS-stricken mother Janis was one of the last people to see her alive. Success came early, when a rapacious music industry in search of new, raw, earthy talent to reinvigorate a scene made etiolated and boring by a profusion of plastic, manufactured, barely musically literate ‘stars’, discovered and greedily promoted Amy before she was ready for the acclaim or the fame.

Winehouse not only had star musical quality – her sad songs a mix of blues, jazz and soul, sung in husky, deep contralto tones – she also had the backstory to go with her material. In many ways she was a throwback to the self-indulgent Sixties, which spawned four of her co-casualties in the 27 Club. Her ‘private’ life, which spilled over into her increasingly tragic and incoherent public performances, was one long story of deepening drug addiction, alcoholic binges, bouts of rehab, cancelled concerts and violent fights with various boyfriends, notably her on-off ‘husband’ and, according to Sounes, the ‘love of her life’, the hapless and hopeless Blake Fielder-Civil.

Her songs – especially her hit album Back to Black – reflected her ongoing misery, and it was clear that she would not make old bones. The end was also typical of the six: a lonely death caused by alcohol poisoning which unnoticed for hours. There were three empty Vodka bottles in her room, but, surprisingly, given her reputation, no drugs. Amy was ‘clean’ at the time of her death. Let down by her last boyfriend, she was eventually found by her live-in bodyguard.

From Winehouse, Sounes moves back in time to the earliest death: Brian Jones. Easily the least sympathetic of the six Stones, Sounes pithily sums Jones up as: ‘Whiney, neurotic, selfish and needy’. His life story encapsulates these characteristics: young and penniless he happily travelled around impregnating young women (he fathered four children, none of whom he knew or supported); until the formation of the Stones gave his life some brief semblance of purpose.

It was not, however, to last. Although a multi-talented musician, Jones’s self-destructive tendencies and his deepening addictions eventually even exasperated his fellow Stones (no strangers to drugs themselves) beyond endurance. Depressed by several Police drug ‘busts’ (‘Why are you always picking on me?’ Jones whined), he became literally unable to perform and a month before his death in the summer of 1969 was formally fired by the other Stones.

Jones was living at Cotchford Farm, the former home of Winnie the Pooh author A.A. Milne, in Ashdown Forest, Sussex. One July morning he was found floating, dead, in his own pool. Although the exact circumstances remain mysterious, there seems no good reason to doubt the coroner’s verdict of ‘Misadventure’. Sounes is suitably scathing about various theories that Jones was murdered – if only for lack of a reasonable motive, or a credible suspect.

Janis Joplin’s death in a Los Angeles hotel room the following year resembled Winehouse’s demise, though heroin, rather than Vodka or Bourbon, her favoured tipple, was the immediate agent of Joplin’s destruction. The wild and raucous rock chick, famous for her animalistic screams, was probably the least talented of the 27 Club (certainly her rock portfolio is the thinnest); and over-indulgence rather than inner angst, seems to have been the motivation. As part of his research, Sounes spent a night in the room where she checked out.

The same month Jimi Hendrix died in London. Having struggled up from poor beginnings, achieving success through his sheer musical abilities (he could pluck tunes from his guitar with his teeth; or play it behind his back) and his exotic ethnic mix: black, white and Cherokee Indian, Hendrix was at the peak of his fashionable fame when he choked on his own vomit.

As with Brian Jones, there have been dark rumours of foul play, but Sounes is equally dismissive of these. Hendrix died after a heroic drinking binge. Hours after his death red wine was still bubbling from his lungs and stomach. As with Jones and Morrison, those around him at the time gave conflicting and garbled accounts of the death; mainly, it seems, to clear themselves of having drugs. This, Sounes suggests, fuelled conspiracy theories of murder.

The next death is that of the Doors’ vocalist, the charismatic ‘Lizard King’ Jim Morrison. As with Jones and Hendrix, Morrison’s exit, officially attributed to a heart attack while taking a bath in his Paris apartment in July 1971, has spawned conspiracy theories because of the strange circumstances. The major ‘alternative story’ is that the singer perished after a massive heroin overdose (a drug he was unused to: Jim being a juicer rather than a junkie) in the toilet of a sleazy club. It is then alleged that the dealers who supplied the smack manhandled his body back to his apartment and dumped it in the bath to cover up their role.

Sounes holds no truck with this theory either; but believes, as with Hendrix, that the only witness to Jim’s demise, his long term girlfriend Pamela Courson, a heroin addict herself who died of an overdose soon after her lover, obfuscated the circumstances of his death to get herself out of possible trouble. He thinks that Morrison, depressed, in poor health, having fallen out with the other Doors and facing a possible prison term back in the US, took a massive overdose of heroin, careless as to whether he lived or died.

At this point Sounes seems to believe that there is a sort of inevitability about this sequence of deaths. That being a 60s rock star was as precarious as the brief life of a subaltern on the Somme. It is instructive, therefore, to remember that those who fell by the wayside are vastly outnumbered by the number of tough old rockers who not only survived but are rocking yet. There are five Stones still touring, and waving rather than drowning. For every Jim Morrison there’s a Van Morrison (the two bad boys were early friends) gloomed and apparently doomed, but still with us. The Who, who hoped to die before they got old, have got certainly old – yet, strangely, are still alive.

Finally, after an interval of more than two decades, Sounes comes to grunge rocker Kurt Cobain of Nirvana, the only one of the sextet to have died from a quick as opposed to a slow, suicide: from a gunshot. The same familiar tale of self-hatred, self-destruction and ruinous over-indulgence in drink and drugs unfolds.

This book is the first time that these committee members, as it were, of the 27 Club have been buried together under the same cover. If Sounes has any profound point to make beyond the obvious one that fragile or self-destructive personalities, given unlimited access to booze and dope and the rackety life of rock ‘n roll stardom, are likely to become casualties, it has escaped me. Nonetheless, to any old rocker, this memento mori of a dangerous age, when the fun was always lapped by a darker margin, is a gruesomely enjoyable read.

Nigel Jones’s biography of an earlier 27 Club member ‘Rupert Brooke: Life, Death & Myth’ is being re-published by Head of Zeus next year.

————–

Amy 27: Amy Winehouse and the 27 Club by Howard Sounes ( Hodder & Stoughton. 480pp. Published: July 18th 2013)

Comments