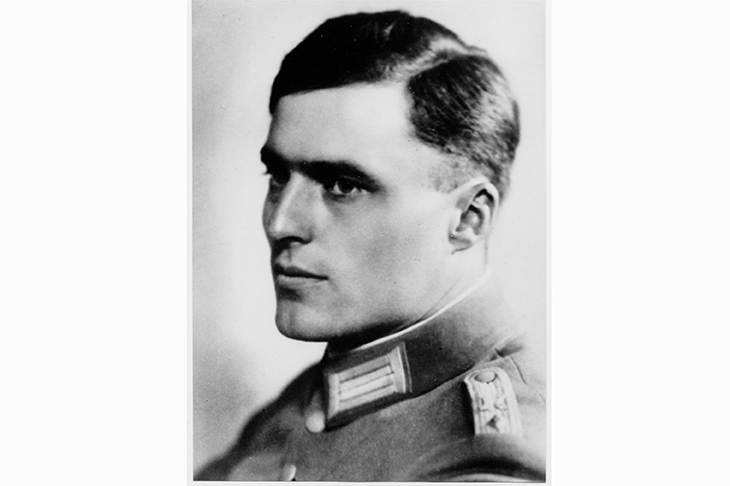

On 20 July, Germany’s political elite recalls the day in 1944 when Colonel Claus Schenk Count von Stauffenberg exploded a bomb intended to kill Hitler, and ran an abortive coup which ended in his own death and that of other plotters. To mark the anniversary, a military band in Berlin will thump out ‘Prussia’s Glory’, whereupon Defence Minister Ursula von der Leyen will urge massed recruits to emulate the rebels’ ethics.

Many of us know these events from the 2008 film Valkyrie with Tom Cruise as Stauffenberg and Kenneth Branagh as co-conspirator General Henning von Tresckow. But in Germany, the ‘Berlin republic’ will be celebrating nothing less than itself, for the failed coup is at the core of the new narrative it has crafted to explain the country’s Nazi past.

This tale holds that a group of Nazi fanatics led by Hitler captured the state, so the German people were victims rather than accomplices. The story of how the frondeurs tried to remove the Führer richly animates the idea of an oppressed German Volk resisting the evil Nazis. Uncomfortable truths (the plotters were a tiny band, most had been Nazis or enthusiastic supporters) have not been allowed to get in the way. Much more unpalatable, but yet to be absorbed, are discoveries which the archives are still yielding. They show the full extent to which key players, such as Stauffenberg himself, were full-blown Nazi criminals before they ever came to oppose the regime.

A reckoning with such facts will be tough. After all, the Ministry of Defence is in the Stauffenbergstrasse in Berlin, the army schools officers at its Stauffenberg barracks in Dresden, and the Bundeswehr runs global missions from the Tresckow base near Potsdam. There will be repercussions in the EU, too, for the new Teutonic tale has fed the Union’s own historical revisionism.

According to this alternative history, Germany was not vanquished in 1945, but was liberated from those alien ‘Nazis’, just as France or Holland were. There is no place for Winston Churchill and his epochal decision in May 1940 to continue to fight. The Holocaust was not a German enterprise — it was wrought by Europe-wide racism. Here truths are suppressed, cause and effect reversed, and scale and scope deprived of meaning.

Berlin has itself to blame for much of the messiness surrounding these myths. The story of ‘Nazis-as-occupiers’ of Germany, and of its core 20 July component, began at a time when the prevailing German doctrine was that the Wehrmacht had been honourable, and that Nazi crimes were down to the SS alone. In the 1990s German historians were exploding the ‘clean Wehrmacht’ legend, but officialdom paid no heed and raised the putsch to its totemic heights. By 2007, when Hollywood was making Valkyrie, the younger generation of researchers had proved that the army had a major hand in the Holocaust and other crimes. Had the filmmakers only asked, they would have heard that Cruise and Branagh were playing men who were deeply implicated. The people they portrayed would all have merited trial for war crimes or crimes against humanity.

Key players, such as Stauffenberg, were full-blown Nazi criminals before they opposed the regime

For Stauffenberg and Tresckow, the charge sheets might have started in 1939 when, as senior military men invading Poland, they aided the SS Einsatzgruppen squads in murdering thousands. Stauffenberg’s division was implicated in burning 70 Poles and Jews alive in a barn; his people were there when the Germans staged a pogrom to ‘celebrate’ Yom Kippur; he welcomed ethnic cleansing and German colonisation. Tresckow was directly involved in atrocities too. During and after the fighting, 20,000 Poles and Jews were unlawfully put to death, but in the classic accounts Stauffenberg and Tresckow noticed nothing.

From late 1940 to early 1943, Stauffenberg was a key aide to the head of the army’s high command, General Franz Halder. The future frondeur shaped the invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941. This saw the German army run mass executions, starve more than three million POWs to death and support the Einsatzgruppen in shooting 1.2 million Jews and 800,000 others. In 1942 Stauffenberg planned compulsory labour culminating in the induction of

3.6 million Soviet civilians — men, women and children — into slavery in Germany and Austria. Tresckow helped lead the Army Group Centre, the largest force to invade Soviet-run territory, so shared in myriad army crimes. We know his people murdered and helped the Einsatzgruppen to kill. By the end of 1941 he had presided over the death of a million Soviet prisoners left to starve and freeze.

The earlier German orthodoxy was that the rebels became active in early 1942 in revulsion at the shootings of Jews in Ukraine. In light of what we know, this is absurd. We can be sure that what fuelled the revolt was the realisation by general staff men such as Stauffenberg and Tresckow that Hitler was leading them to defeat. The rebels always knew what the regime was up to. Take Tresckow. He spent months in German-ruled Warsaw in early 1941 when the occupiers were starving 460,000 Jews crammed into the ghetto before gassing them to death. Mad though it sounds, the Warsaw ghetto was then an almost obligatory ‘tourist’ destination for the German army, a sort of ghastly theme park where your prize could be furs or jewels had for nothing from a Jew desperate for a few potatoes.

While many of the plotters had close links with Britain, they did not learn much. Stauffenberg had been foxhunting in the shires. The leaders of their think tank, the Kreisau Circle, had all studied at Oxford. The plotter Adam von Trott, a former Rhodes scholar, befriended future Labour cabinet ministers such as Richard Crossman, and was chums with David Astor (who edited the Observer until 1975) and Peter Fleming, brother to Ian of James Bond fame. Trott was in England in the summer of 1939 meeting the foreign secretary, Lord Halifax, and the prime minister, Neville Chamberlain. The rebels kept up with Anglo-Saxon thinking to the end, but rejected it outright (the Atlantic Charter and the Beveridge Report were both scorned). Instead, they concocted reactionary schemes which were either risible (for Germany’s internal governance) or ominous (for continued German rule over Europe). For these and other reasons, Churchill and Roosevelt rightly refused any contact with the conspirators. But they were not aware that if the putsch had worked, the UK and US would have faced a German administration stuffed with killers and accomplices. Albert Speer might have been a minister, Tresckow would have run the police.

Then there was Stauffenberg’s friend Fritz-Dietlof Count von der Schulenburg. An intermittent Kreisauer, a leading frondeur and a rabid Nazi, Schulenburg was deputy head of the Berlin police during the Kristallnacht official pogrom in 1938. When ruler in Silesia in 1939-40, he urged the murderous Einsatzgruppen into Poland, planned ethnic cleansing for Himmler and expelled the region’s Jews. In the Crimea he joined army men who led the local holocaust. As late as 1943 he was designing German dominance from Belgium to the Baltics. This criminal creature was to manage Germany’s Ministry of the Interior, no less.

If German and other historians know such facts about the leading frondeurs, why have they not forced them into the public domain? The answer has to be their own diffidence, plus the sheer strength with which 20 July has come to grip the German mind.

Thankfully, recent history takes a prominent place in German discourse. Only last month the right-wing Alternative für Deutschland party (with 16 per cent in the polls, it is snapping at the heels of the Merkel-led government) caused uproar by pooh-poohing the impact of Hitler when seen against the country’s 1,000 years of achievement.

So when it finally does come, expect the public demolition of the Stauffenberg putsch myth to be explosive within Germany. It will reverberate across Europe, too.

Matthew Olex-Szczytowski is a banker and historian. He has researched the 20 July plotters in the German and Polish archives.

Comments