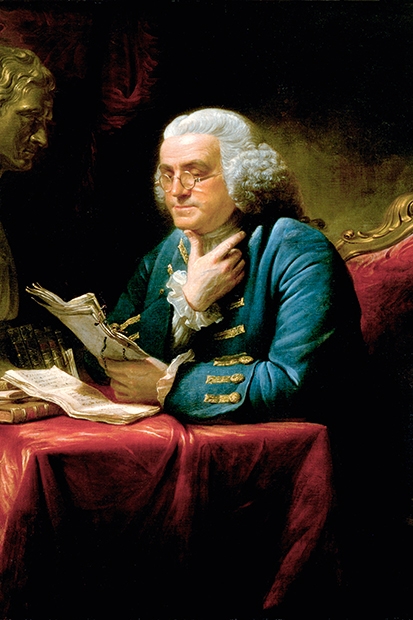

Just who was Benjamin Franklin? Apart, that is, from journalist, statesman, diplomat, founding father of the United States, inventor of the lightning rod, the Franklin Stove, the milometer, swimming flippers and the flexible catheter, the man who engineered the America postal system, who established the first lending library, who wrote one of the finest autobiographies in the language, and who schooled us in soundbites such as ‘Let all men know thee, but no man know thee thoroughly.’ Amen to that. Despite being the subject of a steady flow of worthy biographies, of which this is the latest, Franklin remains as cunning in heaven as he was on Earth.

A master manipulator, people saw in Franklin what he wanted them to see. Even his autobiography, says George Goodwin, with its ‘seeming openness’, was ‘a clever piece of self-protection’. Presenting himself as a teller of tales and dispenser of sound advice, Franklin omitted in these pages any mention of his contributions to science. It was as if, as one of his critics has put it, Einstein wanted to be known for his anecdotes of childhood. To his fellow Americans, Franklin, the youngest son of a soap-maker, was the spirit of the New World; a thrifty folk hero of rustic tastes and middle-class aspirations. To his fellow Brits (Franklin always considered himself British) he was the cultivated European, a child of the Enlightenment, a club-man, wit, womaniser and wily politician. In America he was one of the people; in England he belonged to the elite, alongside his friends Sir Francis Dashwood, Erasmus Darwin, Joseph Priestley and Edmund Burke.

Franklin was at home in London. He went there first in 1724 as a young printing apprentice open to experience, and he spent his earnings in the theatres, inns and brothels. The city was then, says Goodwin, in a state ‘of newness’. When he returned in 1757, as a diplomat for the Pennsylvania Assembly, Franklin was famous, and on his guard. Accompanied by his illegitimate son William (whose mother’s identity remains a secret), Franklin left his other children behind together with his wife, Deborah, who was frightened of the sea (a phobia Goodwin compares with that of ‘air travel today’, although it might just as well be compared with that of sea travel today). Franklin was not overly concerned with the welfare of his family. ‘It is now nine long months since I received a line from you dear Debby,’ he wrote in 1774, five years after she suffered an incapacitating stroke. ‘I have supposed it owing to your continual expectation of my return.’ Debby died a few months later and when, in 1775, Franklin eventually left England, it was to avoid arrest. The British government, he now believed, saw their American cousins as ‘the lowest of mankind, and almost of a different species’. Aged 70, Ben Franklin became a revolutionary.

The focus of this dull but honest biography is the tangled political machinations of Franklin’s 18 years in London; Goodwin’s Franklin is the public figure rather than the inventor of genius. Like Franklin himself, Goodwin refuses to provide us with the man in full or to lead us to the point where the politician and the electrician meet. Moving from fact to fact, he defers to others for analysis. Jerry Weinberger, quoted by Goodwin, observes:

He was moved to politics, in my view, not by pride or anger and certainly not by any sense of moral obligation, but rather because he liked it, as much as he liked chess, and … Franklin did what Franklin liked.

It is the best insight in the book.

Between battling with Thomas Penn over taxation in Pennsylvania and trying to build a ‘special relationship’ between colony and coloniser, Franklin uncovered the cause of the common cold, invented a three-wheel clock, the glass harmonica (whose tones can apparently be heard in the Harry Potter films), and a damper for chimneys and stoves. He also investigated lead poisoning and magnetism, and drew the first map of the gulf stream. These achievements, which belong to his London years, are glossed over by Goodwin in a sentence: we are never invited to see Franklin in his laboratory, to watch his vast mind at work, or to follow his thoughts as an idea takes form. Similarly, Goodwin notes without comment that it was during his time in England that Franklin wrote the first 25,000 words of his autobiography, as though beginning a book — especially a book as complex as this — were simply a process of holding a pen.

To Franklin’s contemporaries, who were keen on drawing connections, politics and science were close relations. John Quincy Adams put it perfectly when he described Franklin’s return to America as the moment when his ‘electric rod smote the earth and out sprang General Washington. Then Franklin electrified him, and thence forward those two conducted all the policy, negotiations, legislations, and war.’ This undercharged biography would benefit from a similar bolt.

Comments