It is not a criticism of Philip Almond that The Lancashire Witches, published to mark the 400th anniversary of the Pendle witch trials, is a depressing read. On the contrary, Almond has produced a fine and lively study of the events in 1612 when eight women and two men were tried for witchcraft.

What is depressing is how ordinary those involved seem to be. This is not a story of gothic horror or bizarre group psychosis. It is a tale of people being caught out for doing relatively ordinary things.

The Pendle witches were not members of some pagan or Wiccan cult, or even genuine devil-worshippers. As Almond makes clear, much of the folklore and superstition that came to be called witchcraft had previously been part of life. Consequently the supposed witches were really members of a typical rural community subject to the machinations of outsiders keen to make a name for themselves.

The catalyst for this was the arrival of James I on to the English throne. James brought with him a Scottish credulity towards witchcraft at odds with the more tolerant English tradition. He even wrote a book on the subject, called Daemonologie. As Almond explains, judges like Edward Bromley and James Altham, who heard the Pendle cases, curried favour with the king by trying to weed out witchcraft. In looking for it so vehemently they found it in abundance.

In Pendle their agent for this was a Puritan preacher called Roger Nowell. He was a notorious witch-hunter who falsely promised leniency to those he accused if they in turn accused others. But at the centre of Almond’s book is the court clerk in Lancaster, Thomas Potts, who was commissioned by Bromley and Altham to publish the Pendle witch trials as a book. Their aim was to boast of their success, but they also sought to justify themselves against the popular feeling that they had executed innocent people.

Quite what ‘innocent’ meant in terms of James I’s Witchcraft Act of 1604 is a good question. Earlier laws on witchcraft only made it a capital offence if someone was killed, or the witch was a serial offender. But with James I almost any form of witchcraft was punishable by death. As Almond notes, some of the Pendle defendants tried to claim they had been tempted by the devil, but they had resisted. Unbeknown to them, by admitting they had ‘consorted’ with the devil, even to reject him, they still condemned themselves as witches.

In other cases, neighbours used the draconian new laws to take revenge, often for petty slights. Alizon Device was accused of witchcraft for cursing John Law when he refused her begging. Law later twisted his ankle and blamed Device for bewitching him. Anne Whittle was accused of witchcraft after being called to help cure a neighbour’s sick cow, presumably using a folk remedy. When the cow died the neighbour claimed Whittle had actually cursed it.

Although charges of witchcraft remained rare in England, and conviction was not a foregone conclusion, there is a sense here that there was nothing the victims could do to escape the gallows. In an attempt to rally support, relatives of those first arrested called a meeting at a place called Malkin Tower. As a result they too were charged with witchcraft and accused of holding a black sabbath.

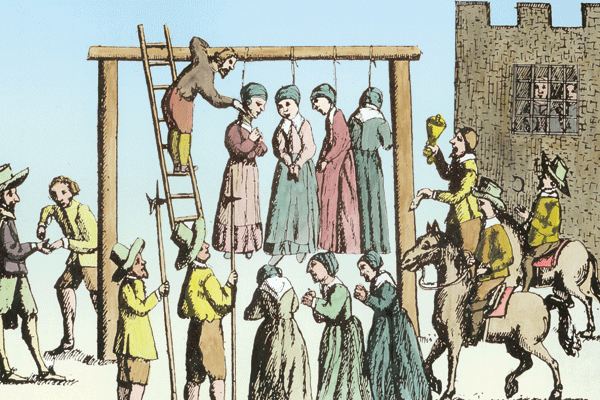

All ten of those tried for witchcraft in Pendle were hanged. A few decadesater the fanatical witch-hunter Matthew Hopkins would make this seem almost lenient. But in 1612 it was the largest single execution of witches England had ever seen.

Comments