Much is now being made of the evils of empire. As a child of empire I bridle. I acknowledge the wrong and injustices of colonialism, the racism, and the greed too. I accept that a re-balancing of history was due. It’s good that the darker side of the picture has now moved into the light.

But from my own boyhood experience I know that mixed among the aims of empire there were also idealism, principle, and a belief in the betterment of those we governed. And success: there were things to be proud of. The roots of my mix of pride and shame about empire are the impressions a white boy in Africa formed of the continent on which our forefathers had landed. I cannot ignore, as some anticolonial opinion does, the situation they came to.

What is now Zimbabwe (for instance) was not a stable, peaceful and kindly society. It was the front line of an immense and violent land-grab by one tribe — the warlike Matabele — from another, the peaceful, pastoral Mashona already settled there. This will have been accompanied by rape, pillage and murder as the Mashona majority were driven out. The arrival of a third party, Cecil John Rhodes, with his own version of expropriation, froze the conflict for about a century. Stability was achieved — at a cost. But the horrors that had gone before remain lodged in the unconscious folk memory of the Mashona people, and you can see in today’s persecution of the Matabele minority by an essentially Shona government the 21st-century reverberations of a vicious 19th-century territorial war.

I’m hardly qualified to drill deeper into that contested history, beyond saying this: in apportioning our guilt about the wrongs of colonialism, we do need to take account what went before. That older Africa was not a neutral, benign tabula rasa on which we scrawled our peculiar European obscenities. There were different obscenities already there.

I was put in mind of this a couple of weeks ago, spending an afternoon at the marvellous Peru exhibition at the British Museum. This cannot be praised too highly, deserving all the acclaim it has met. Priceless objects have been set in a beautifully drawn picture of the geographical and social landscape they inhabited. The rise and fall of the Incas and of their culture is evocatively described. The often overlooked importance of the empires and cultures that the Inca empire displaced is placed in proper context.

The truth is that all empires in all cultures and through all history have expanded in the same way

But for me something grated in this exhibition, crystallising in my mind when I read one of those accompanying explanations that exhibitions give you as you stare at the exhibit. The Inca empire, it said, grew to predominance by ‘negotiation and alliances’ with existing cultures and their territories.

Oh no it didn’t. Like the expansion of any empire, some of it was accomplished with, and some without, bloodshed; but even the peaceful ‘negotiations’ and ‘alliances’ were achieved with the threat of force always in the background. On the reasoning implied by that explanation, you could protest that our own empire expanded often without a shot being fired. Yes, but the gunboats were ready.

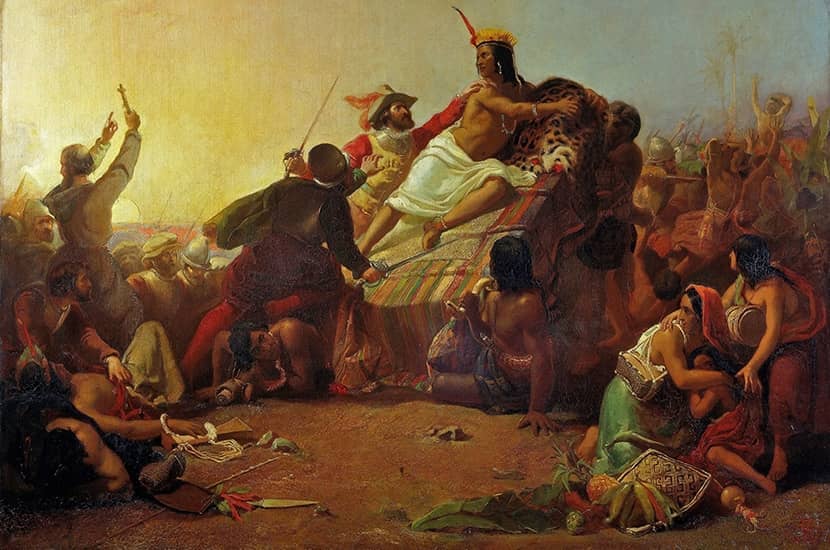

Moving chronologically through the exhibition hall, I reached the Spanish conquest. Correctly, the accompanying notes described the extraordinary cruelty and rapacity of the early Spanish empire and one wouldn’t have changed a word of that. The blood runs cold at the barbarity of the conquistadores and their colonialist successors. Even today, the shame should lie heavy on modern Spain. In history, Simón Bolívarand his revolutionary secessionists have made a lucky escape, passing their revolution off as a struggle for self-determination from Madrid, when in reality Bolívar was the Ian Smith of his day, unilaterally declaring independence, but not for the oppressed South American Indians: rather for the colonialists, who continued to persecute and massacre the natives right up until the 20th century. Latin South America is fortunate that, because it never translated its crushing of brown-skinned peoples into formalised structures of apartheid, the racial oppression largely escaped the 20th century’s notice.

So I dissented not from the exhibition’s treatment of European colonialism, but from its implicit exoneration of Inca colonialism. The truth from which fashionable academic commentary seems to shrink is that all empires in all cultures and through all history have expanded in the same way. The truth is ducked because it suggests another truth: that there is something inevitable about this.

When it comes to describing the status quo that arriving colonialists encountered, there’s self-censorship going on. This was reinforced by the exhibition’s virtual silence about the environmental wreckage that millennia of indigenous peasant farming have visited upon the ecology of the Andes. The range was once heavily forested below its peaks. But thousands of years of burning, wood-gathering and llama-browsing have devastated that environment. Every year the Andes are shrouded in a smoky haze as farmers burn the forest back.

Commentary in exhibition notes seemed to suggest a human culture living in harmony with nature, cherishing ‘Pacha Mama’ (Mother Earth). This is self-hating green nonsense. There was no golden age of harmony with nature. Destructive modern agricultural methods may have replaced destructive indigenous practice, but humans and ‘nature’ have always been at war. Only disease and climate change, suppressing population growth, ever inhibited peasant farming from ravaging the wild more completely.

This is true even in Britain. Small farmers are no more environmentally responsible than big farmers. They are smaller, that’s all. Critiquing our own age — a critique I mostly endorse — our post-modern view has supposed it necessary to conjure up a former paradise, the myth of Eden — a kinder, peaceful, stable, green, humane and compassionate world — which we’re said to have spoiled. It never existed. To examine present sins, we should not posit past innocence.

Comments