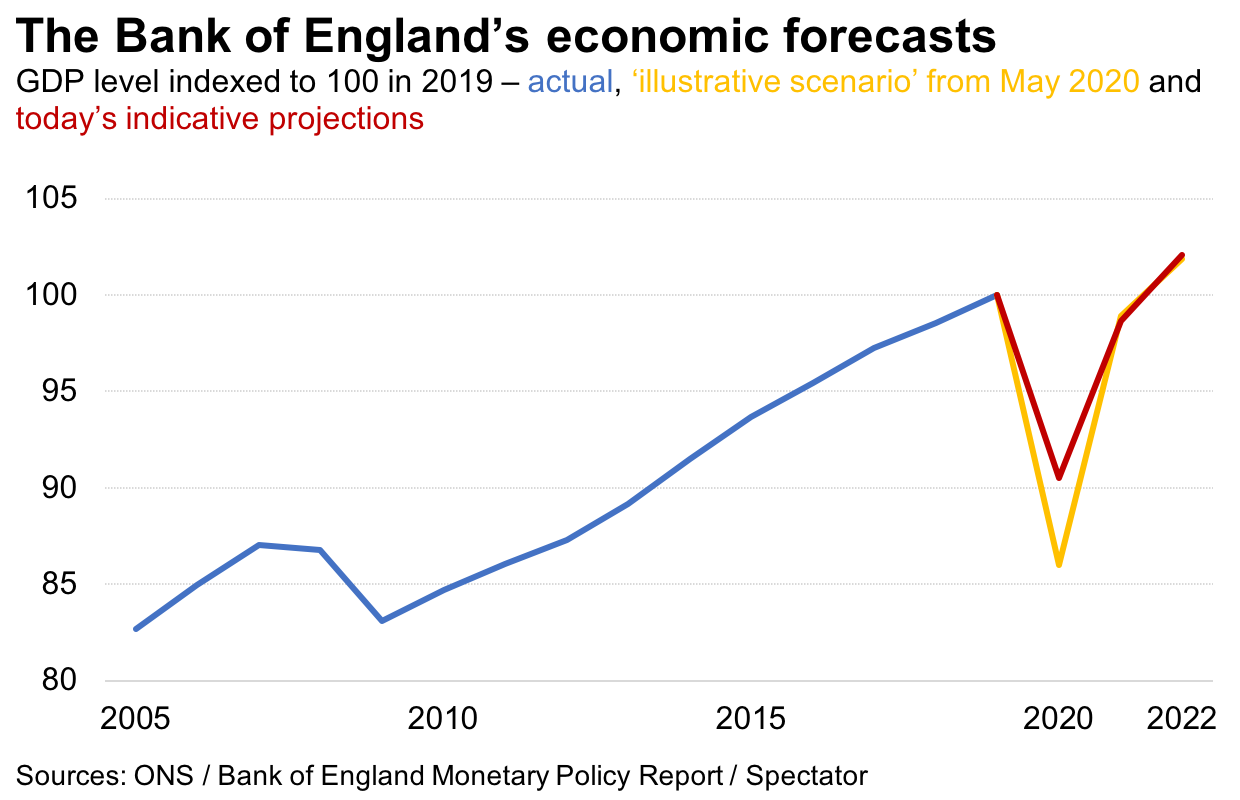

The Bank of England offers a mixed bag of forecasts today. It now expects Britain’s economic downturn to be less extreme than feared, while also predicting a recovery will take longer than originally thought. The Bank now expects the economy to contract 9.5 per cent in 2020, substantially less than the 14 per cent drop it predicted at the height of the national lockdown. But it joined the Office for National Statistics in revising its optimism for a sharp V-shaped recovery downward, expecting nine per cent growth in 2021, with GDP not returning to pre-Covid-19 levels for another eighteen months.

The Bank’s forecast remains one of the most optimistic, still showing the resemblance of a V-shaped recovery. But are these scenarios accurate reflection of what’s to come?

Crucially, today’s forecasts include two major assumptions: that there is not a second wave of the virus and that the UK exits the European Union in a way that avoids major disruption. Neither of these scenarios is remotely guaranteed.

While it is not yet clear if Europe is really experiencing a second spike of the virus (or the lingering effects of the first wave) governments are treating a rise in Covid-19 cases as the former and reintroducing rules and restrictions for local areas to reflect these concerns. No. 10 is adamant the UK will not go into a second national lockdown, yet its local shutdowns so far are encompassing entire cities in England and Scotland, having major effects on economic rehabilitation in those areas.

What’s more, there is no guarantee that the UK and the EU will end up with a Brexit deal. As James Forsyth explained in The Spectator: ‘The Covid-19 crisis has served only to stiffen No. 10’s resolve: coronavirus has collapsed world trade and travel, dwarfing any changes Brexit might bring. We are over that cliff edge already, along with everyone else.’ The incentive to strike a deal with the EU, especially one British officials don’t think is reasonable or fair, has significantly diminished since January.

More telling than the Bank’s predictions perhaps are its latest round of decision-making, which includes ruling out negative interest rates for the foreseeable future. The Bank’s Governor Andrew Bailey told Sky News ‘there’s no reason not to have them in the toolbox… but we’re not looking to implement them at the moment’. This has led to peculation that such a policy could be adopted later on in the year, but concerns over how negative rates would impact banks’ ability to lend and what it would mean for customers storing their assets have put the idea on the backburner for now.

Meanwhile the Bank held interest rates at 0.1 per cent – an unsurprising decision, but one that will still bring a sigh of relief to the Treasury, which can’t finance its response to the Covid-19 crisis with anything other than ultra low interest rates, not to mention hundreds of billions of pounds of printed money. The Bank has also stuck to its bond-buying target of £745 billion, though analysts expect the Bank to pursue more stimulus later this year. But it serves as a reminder that it is always in the Bank’s gift to sustain or cut off the government’s plans for Covid-19 support packages and recovery. While the Bank’s predictions matter, the levers it can pull matter far more.

Comments