What are your thoughts on assisted dying and assisted suicide? That’s the question asked by a Health and Social Care Committee consultation, closing today, that could shape changes to the law on euthanasia. Having had intimate experience of what can happen when a vulnerable person feels themselves to be a burden, I’m against.

My mother had Parkinson’s, and once she burst out to me that: ‘You’d have so much more time and money if it weren’t for me’. It would be the easiest thing in the world to push someone in that condition towards feeling that it would be better for everyone if she were given a dignified death. Actually my mother did have a dignified death, at home, even though, by then, she had to have everything done for her.

The other reason to avoid assisted suicide is that we’ve already seen how it turns out

The notion that families must always have the best interests of their vulnerable relatives at heart is risible. Doubtless most do, but a friend who works as a health care assistant and does end of life plans with elderly patients in London tells me about cases where children want what’s best for them, not their relations: viz, the parental property; one lady begged him not to let her daughter know if she were dying because she was scared of her.

The other reason to avoid assisted suicide is that we’ve already seen how it turns out. There would be umpteen safeguards around any euthanasia legislation, but what has happened in other civilised jurisdictions is that the slippery slope has become a black run: within a decade or so, groups that were unlikely to have been envisaged as candidates for assisted dying are included on humanitarian grounds.

The Dutch government approved extending euthanasia for terminally ill children between the ages of one and 12 if the parents wanted it. No scope for autonomy there. People with psychiatric disorders are also eligible, as in the case of the 29-year-old Aurelia Brouwers who was euthanised in 2018 at her own request because of her chronic depression.

The euthanasia law in the Netherlands, introduced in 2002, doesn’t require that a patient be close to death. An applicant’s request must be ‘informed’ and ‘voluntary and well considered’; the doctor must be satisfied that the patients has ‘unbearable suffering without prospect of improvement’ and there is ‘no reasonable alternative’ to address it.

In both the Netherlands and Belgium, patients with dementia can be euthanised. Again, where’s the autonomy there? These are respectable, humane and civilised countries. But once the principle that doctors may wilfully kill their patients was established, the demand for extending the legislation has grown.

One outspoken proponent of the benefits of assisted dying in the Netherlands is Dr Bert Keizer, who worked for what used to be called the End of Life clinic. Writing in the Dutch Medical Association Journal, he compared the euthanasia laws with those around abortion, which were initially tightly drawn and later relaxed:

‘And so it was with euthanasia. Every time a line was drawn, it was also pushed back. We started with the terminally ill, but also among the chronically ill it turned out to be hopeless and unbearable suffering. Subsequently, people with incipient dementia, psychiatric patients, people with advanced dementia, (high) elderly who struggled with an accumulation of old-age complaints and finally (high) elderly who, although not suffering from a disabling or limiting disease, still find that their life no longer has content.

‘Looking ahead, there is no reason to believe that this process will stop in case of incapacitated dementia. What about the prisoner who has a life sentence and desperately longs for death? Or doubly disabled children who, although institutionalised, suffer unbearably and hopelessly according to their parents as a result of self-harm? I don’t believe we are on a slippery slope, in the sense of heading for disaster. Rather, it is a shift that is not catastrophic, but it does require that we continue to get involved as a community.’

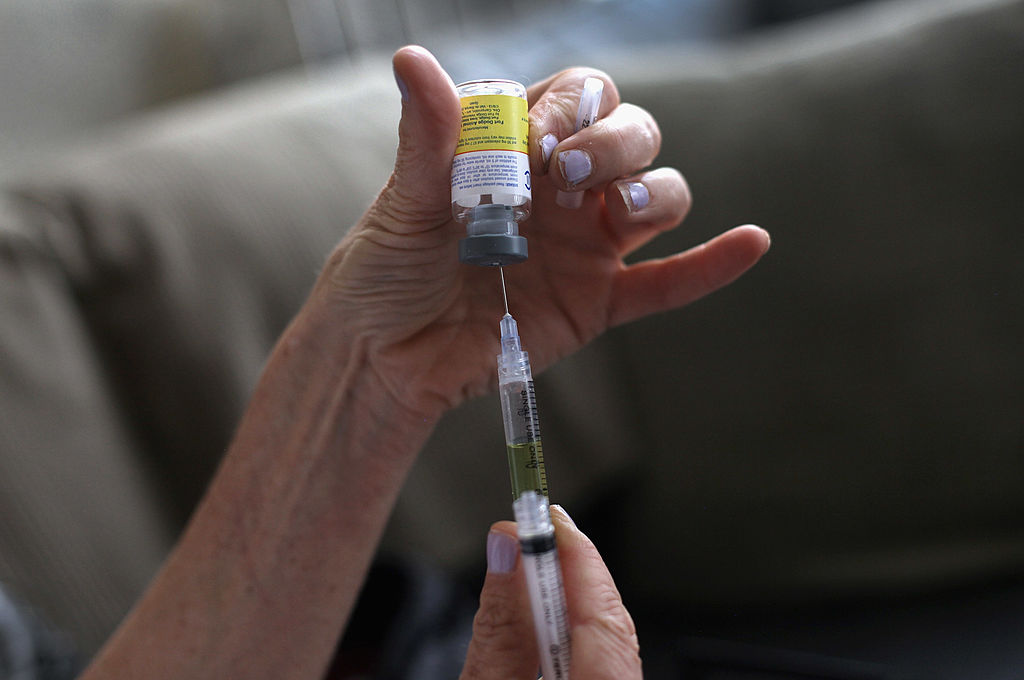

That’s what happens. I’d say it’s preferable to have the law that holds in Britain: that where patients are in great pain they may be given pain-relief like morphine which may have the effect of ending their life, but that’s not the purpose of administering it; what old fashioned moral philosophers call the principle of double effect. I’d say one reason the UK doesn’t have assisted dying is that there is already assisted dying in the excellent hospice system which this country pioneered under the leadership of Dame Cecily Saunders and others: they assist you to die in your own time and more often than not in your own home, and they don’t kill you.

Do take part in the consultation. One of the things about public consultations like this one is that quite often they’re not quite public enough and it’s just lobby groups who pass round the details. So, when the outcome of the consultation is announced, the outcome can be skewed.

But bear in mind, when you fill out your response, that euthanasia has been tried elsewhere – and the results are very troubling.

Comments