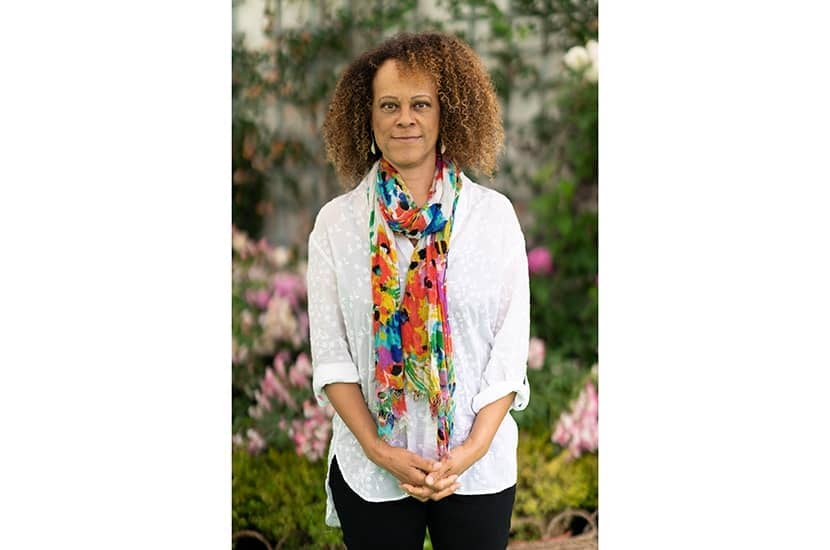

Bernardine Evaristo’s Manifesto — part instructional guide for artists, part call to arms for equality, part literary memoir —shimmers with unfailing self-belief and a strong vein of humility. When Evaristo won the Booker Prize in 2019 for her magnificent seventh novel Girl, Woman, Other,

the first black woman to do so, it was the pinnacle of a career devoted not just to honing her craft but to helping others traditionally excluded from the literary world, through teaching, mentoring and activism.

There is a great deal of style to Evaristo’s life story; her childhood has strong storybook notes. Her home was a huge, rundown house in south London with 12 rooms, eight children and a bannister valiant enough to bear them. In their front room stood two broken antique pianos. The young Bernardine dreamed of formica and linoleum. Her white, Catholic, teacher mother was a terrific home-maker, insisting on healthy eating and tons of cuddles. Her children competed well into their teenage years to massage her tired legs at night. Her black, Nigerian, welder father, Julius, a strict disciplinarian, had an approach to home improvements which wasn’t suited to the human lifespan — a bath languishing uninstalled against the bathroom wall for several decades. (Beat that.)

It was a political household, and proud to be so, her father working as a Labour councillor and shop steward, her mother the union rep at the school where she taught. Yet Julius’s extreme strictness, his frequent recourse to the wooden spoon and the belt and the hour-long lectures that preceded these punishments meant his children often lived in fear. Additionally, Evaristo’s mother’s family’s vehement opposition to her marriage to a Nigerian wounded the children’s sense of identity. ‘We grew up knowing that some of the people who should have been closest to us disapproved of us to the extent they had nothing to do with us.’ In Manifesto, painful things are stated quietly, often briefly, and then left. Respecting your own privacy is in keeping with Evaristo’s moral code.

From an adolescence enriched by participation in youth theatre, enhanced by rainbows of self-made stripey garments, the young Evaristo came into her own. She progressed to drama school and a career in theatre, going on to found Britain’s first black women’s theatre company. It was writing poetry, however, drawing on new knowledge and insights into her childhood and African heritage, often while sipping whisky and listening to Edith Piaf, that precipitated a cultural awakening.

From this period there emerged the conviction that she must nurture and feed her creativity, above all, living frugally, moving house frequently, steering clear of relationships that might lead to too much domesticity, doing everything to avoid relegating her art to ‘secondary status’. Evaristo deliberately set out to improve her confidence, with personal development courses, self-discipline and affirmations, setting in place the internal infrastructure required for her to thrive. It was a masterpiece of self-care. Even today she teaches her students at Brunel University, where she is professor of creative writing, to stave off failures and disappointments, even as they occur, so they cannot land.

Manifesto is punctuated by episodes of racism, some shrugged off, some stinging bitterly. Bricks were thrown through the windows of Evaristo’s childhood home, her father chasing the culprits, making their parents pay for the damage caused. When she was 15, a classmate taking sociology O-level conducted a survey. Would you want to live next door to ‘a coloured family?’ Seventy-five per cent of her class answered no. These were her friends. During an audition for the Central School of Speech and Drama a staff member examined Evaristo’s mouth and teeth. The cost of trying to move forward with such ugly opposition is communicated powerfully. Yet it somehow feels like a disservice to dwell on what she has endured rather than what she has achieved.

She writes memorable characters who leap off the page, follow you upstairs and flag you down. I’ll never forget Barrington, the charismatic, maddening hero of her sixth novel Mr Loverman, despairing as one of his wife’s friends from church discusses the size of a friend’s daughter’s uterine fibroids, with great relish, over ‘lumpy tendons’ of goat. Evaristo writes so well about all the different ways of being a family. The cruel, coercive, lesbian relationship in Girl, Woman, Other terrifies me to this day. Her first novel, Lara, treats seven generations of her personal history in verse, with verve and depth. She gives us a mother tortured by the thought of her teenagers, out on the town, who ‘worries herself to sainthood most nights, fearing the briars/of our city’s urban jungle, missing persons/Bill Sikes’. She captures the invincible-seeming father’s anguish following his mother’s death: ‘I am a strong man but pain is a warrior too./ The pit I build for grief this time will be infinite.’

Manifesto’s subtitle is ‘On Never Giving Up’. A better advert for this maxim you could not find.

Comments