For a patriotic German in the decades before Bismarck, Britain’s power was an object of envy. But there was one thing, at least, that you could always hold over the Anglo-Saxons on their foggy little island. On 1 January 1837, Robert Schumann sat down in Leipzig to hear a new piano concerto by the 20-year-old William Sterndale Bennett. ‘An English composer; no composer,’ commented his neighbour, smugly, before the music started. Few 19th-century German music-lovers failed to point out that the land of Shakespeare had somehow failed to produce a single really significant composer since the late 17th century.

We know how that story ended; and if you want to explore the flowering of the British musical renaissance, it’s never been easier. The first recording of Parry’s oratorio Judith (1888) was released this month and recent recordings have put Sullivan back into the limelight without Gilbert for the first time in decades. (Coronavirus has sadly thwarted the Nottingham Harmonic Society’s attempt to revive Hamish MacCunn’s 1905 cantata The Wreck of the Hesperus.) But the picture grows dimmer before the last quarter of the 19th century. Are there riches waiting to be rediscovered further back?

Well, yes and no. For the young British musician of the early Victorian era, the choice seems to have been respectability via the Royal Academy of Music (founded in 1822), or outright bohemianism as an itinerant virtuoso or opera composer. Not that the Academy was all that respectable, initially at least. Its first secretary, the harp virtuoso and bigamist Nicholas-Charles Bochsa, had fled Paris after being convicted of fraud. Its principal was William Crotch (1775–1847) — a former prodigy, whose music resembles Haydn with a coating of Regency stucco. He resigned in 1832, having been caught kissing a female student (she had apparently completed a particularly fine harmony exercise).

Drury Lane’s opera promoter Louis Jullien was an ‘undisputed lunatic’, according to Berlioz

But the Academy soon settled into politeness, instilling a due reverence for Handel and later Mendelssohn — a composer so quintessentially Victorian that in 1842, during a soirée at Buckingham Palace, he played the piano while a starstruck Queen Victoria sang his songs (‘with some trepidation’, she told her diary). British composers struggled to escape Mendelssohn’s shadow, and the still more intimidating influence of Beethoven. Crotch’s pupil Cipriani Potter (1792–1871), known to his family as ‘Little Chip’, actually met Beethoven (who called him ‘Botter’) and wrote a series of lively symphonies before succeeding Crotch at the Academy and drying up. Wagner met him in 1855, and found a man of ‘almost distressing humility’, embarrassed by his own music.

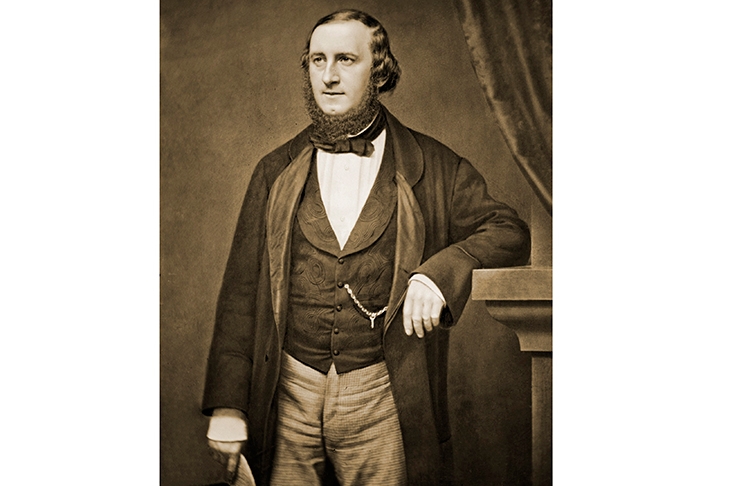

With Potter’s orchestral scores, as well as those of George Macfarren (1813–87) and his pupil Alice Mary Smith (1839–84), you’re reminded of The Life of Brian. ‘You’re all individuals,’ proclaims Beethoven. ‘Yes,’ chorus back his British disciples. ‘We’re all individuals.’ Sterndale Bennett (1816–75) probably comes closest to breaking clear. There’s a captivating freshness and energy about his youthful piano concertos, and even Schumann’s Anglophobic fellow-concertgoer was compelled to admit that Bennett was, indeed, a composer — ‘and truly an angelic one’. Years of dutiful administration at the Academy crushed his spirit. When Bennett overheard two female students playing Herold’s opera Zampa on the piano, he confiscated the score.

It’s a pity he didn’t pause to listen, because amid the raucous, disreputable world of opera and touring virtuosos, signs of really original musical life were starting to sprout in the British Isles. The most significant was the Irish pianist John Field (1782–1837) — the inventor of the piano nocturne, whose adventures took him to St Petersburg and a cameo appearance in War and Peace. Two more Irishmen, Michael Balfe (1808–70) and the soldier’s son William Vincent Wallace (1812–65), abandoned careers as travelling performers to try their luck on the London opera scene.

That was a gamble — and not just financially, though for opera promoters such as Drury Lane’s Louis Jullien (an ‘indisputable and undisputed lunatic’, according to Hector Berlioz) an unsuccessful season meant bankruptcy and the debtors’ prison. This was the great age of the audience riot: Covent Garden installed iron spikes (tastefully gilded) to contain angry crowds, and according to one source, ‘torn clothes and fainting fits’ were common at the opera in the 1830s. When the Swedish soprano Jenny Lind made her London debut in 1847, a witness recorded that ‘the struggle for entrance was violent beyond precedent — so violent, indeed, that the phrase “a Jenny Lind crush” became a proverbial expression.’ Opera-going could be a pungent experience, too: in his essay ‘Pots, privies and WCs: crapping at the opera in London before 1830’, Michael Burden has established that Covent Garden (capacity 2,800) had only two water-closets — and they were both backstage.

This was no place for restraint, and English-language operas of the day were not subtle. In Balfe’s Satanella (1858) a she-demon disguised as a bride is struck by lightning on the way to the altar, the actual bride having been abducted by pirates. But listen to Balfe’s greatest triumph, The Bohemian Girl (1843), and you can feel the same raw, theatrical vitality that you find in early Verdi. When it counted, Balfe could knock it for six — and the aria ‘I Dreamt I Dwelt in Marble Halls’ is so indestructibly catchy that within living memory it was regularly played on Radio 2.

So apart from Sterndale Bennett’s concertos, Field’s nocturnes and The Bohemian Girl, is anything else worth an occasional listen? Possibly Wallace’s Maritana: the barnstorming debut opera by the dodgiest musical adventurer of them all. Wallace had been a roving violin soloist in the colonies, where he advertised himself as ‘the Australian Paganini’. He joined a whaling ship in New Zealand, battled a Maori war fleet and was served human flesh at a cannibal feast (he politely declined) before marrying a chief’s daughter who carved her mark on to his chest with a knife. Or so he told Berlioz, anyway. Arriving back in London, he composed Maritana in 1845. It’s unquestionably melodramatic (Gilbert and Sullivan parody the plot in The Yeomen of the Guard), but its melodies, its colour and its sheer bravura carry the day. It was performed throughout Europe.

If Maritana were translated into Italian and passed off at Glyndebourne as a rediscovered bel canto rarity, it would be hailed as a minor masterpiece. In his 1905 Birmingham lectures, Edward Elgar looked back on British musical history with undisguised disappointment, and it’s hard to dispute his conclusions. ‘We all knew, though we dared not say so […] that Arne was somewhat less than Handel; that Sterndale Bennett was something less than Mendelssohn; and that some Englishmen of later day were not quite as great as Brahms’. But perhaps he was looking in the wrong places.

Hubert Parry’s Judith is available on Chandos.

Comments