The end of term is here and parents up and down the country will be awaiting the arrival of their child’s end-of-term report. But I hope they won’t be expecting too many pearls of wisdom from the impersonal emails that will ping into their inboxes shortly.

Ten or a dozen years ago (the exact date varied, school by school), in an act of educational vandalism, handwritten school reports were abolished. Edicts were issued by school ‘senior management teams’ and grudgingly, reluctantly, teachers put their fountain pens and little bottles of Quink back into their desks, never to be taken out again.

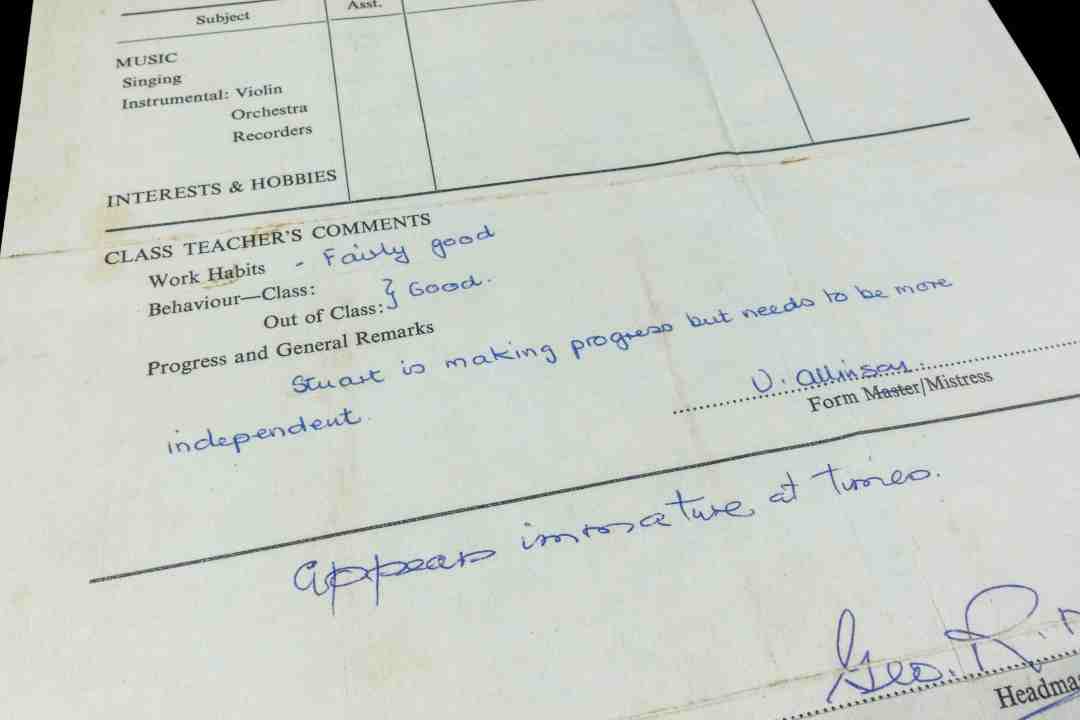

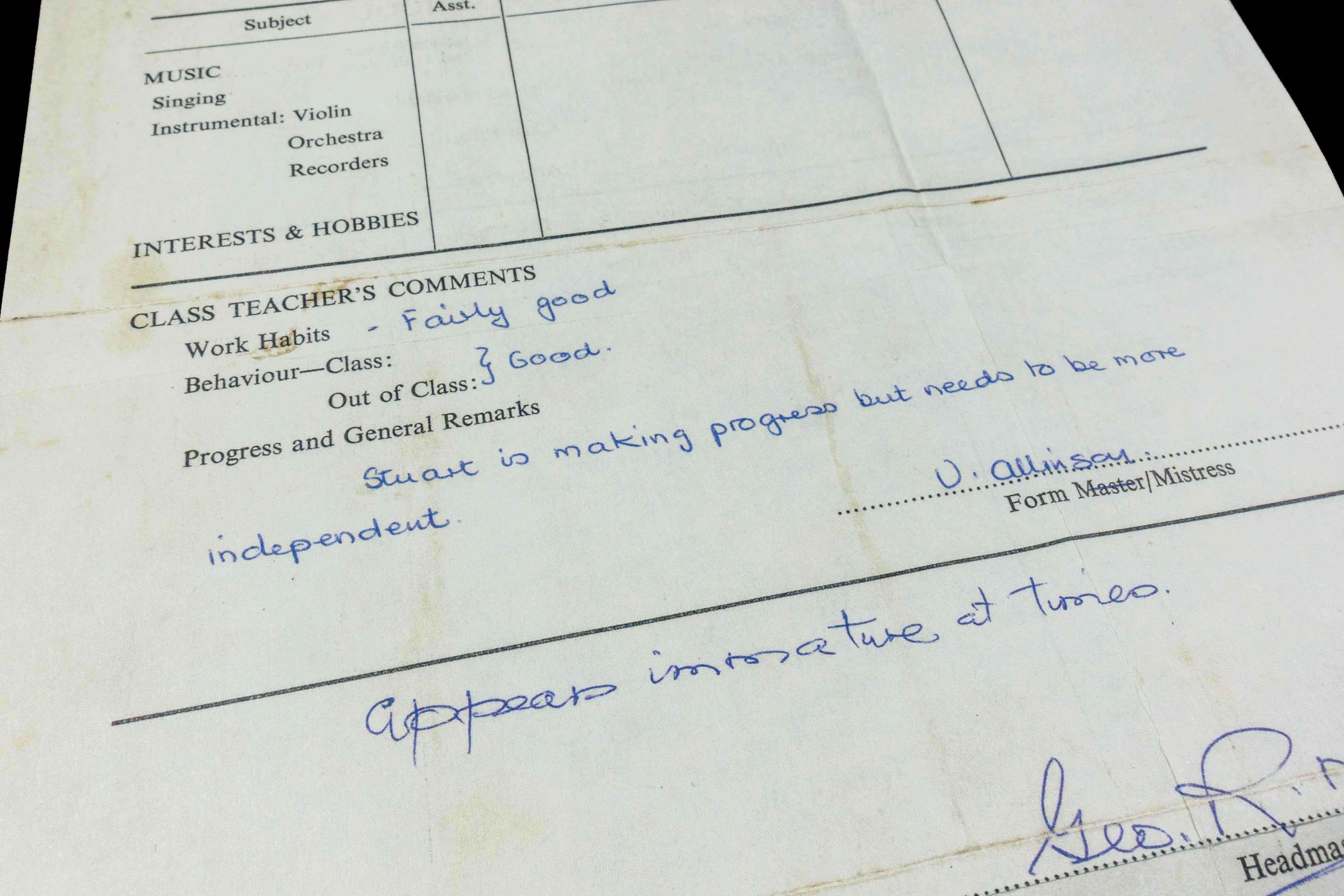

The personal touch in the reporting process disappeared with them. With a flourish of bold, often lurid ink, fountain pens turned even the most banal comments into words of wisdom and parents and pupils alike cherished their individuality. Every show-off in the staff room would pull out the Montblanc, in the mood for some creative comment on a pupil’s progress – or lack of it. This was payback time for all the chattering in the back row they’d put up with. Written off the cuff, such reports were memorable. They even looked distinctive, penned on headed school paper.

Looking at mine now – the spidery scrawl of the science teacher, the flowery prose of the failed-actor English teacher, the jaunty dots and dashes of the history man – I can still see the faces behind the blunt comments

I still have all mine. Each December, I used to pray that a bad report wouldn’t once again ruin Christmas. Fat chance, with comments like these: ‘He is growing up, but slowly’ (aged 13); ‘He is somewhat less of a fool this term, but the difference is marginal’ (aged 14); ‘He finds difficulty, but much of this is due to his unwillingness to overstrain himself’ (aged 15).

Looking at them now – the spidery scrawl of the science teacher, the flowery prose of the failed-actor English teacher, the jaunty dots and dashes of the history man – I can still see the faces behind the blunt comments. They’d never get away with such plain-speaking nowadays. But they were simply telling the truth.

Nor was I alone in dreading the arrival of bad news from school. Many successful celebrities endured far worse comments – among them Gary Lineker, currently the BBC’s highest-paid presenter, who was told: ‘He must devote less time to sport. You can’t make a living out of football.’ Sir Richard Branson’s school report famously informed his parents that he would ‘either go to prison or become a millionaire’.

In stark contrast, today’s reports not only look dull but are full of platitudes rather than offering useful lessons in life. I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve been told by pupils that their parents don’t bother reading them. In a more litigious age, teachers must be wary about what they say and, in particular, about making grade predictions. They could be held to account should exam results in the summer go pear-shaped. Accountability was never something that bothered the writers of those handwritten reports. There were no centralised records, for a start. And with so many blots and squiggles, it was hard to be completely certain whether you’d read some of the comments correctly, anyway.

Of course there were downsides to handwritten reports. If some careless colleague accidentally spilled coffee over the finished pile proudly placed in the staff room before postage, that was it: they had to be done all over again. It happened.

But one unforeseen consequence of today’s computerised system is the temptation it brings for teachers to cut and paste as much of the content as possible, thereby cutting the time it takes to write reports in half. Those reports arriving this week are sure to contain a high proportion of cut-and-pasting. A bland summary of the term’s work, which could apply to any pupil in the class, can be put in at a click of a mouse and take up half the report, saving many hours of labour.

Here’s one example I used for an entire Year 10 English class:

We have had a busy term studying Of Mice and Men and preparing themes of ‘loneliness’ for the exam. As part of the Assessment Objectives, we have also looked at the context of the Great Depression in 1930s America. (Insert name) now has a full revision pack on this vital text.

Click, click, click – job nearly done. It’s quite common, when an over-casual teacher doesn’t bother to check reports carefully, for the wrong name to be pasted into the report; occasionally even the wrong gender. No wonder some parents don’t read them.

Thus the whole concept of personalised reporting is devalued. It’s unlikely that any pupil, however motivated, will save today’s reports for years to come, taking them out from time to time, trying to pinpoint exactly where life went wrong. Which is a pity, as this too should be part of the educational process.

Comments