Polish grandmaster Akiba Rubinstein was one of the strongest players never to win the world title. Up to 1914 he seemed unstoppable, but then the Cuban genius Capablanca burst on to the scene and after the first world war Rubinstein was a changed man. In Chess and Chessmasters (Hardinge Simpole), Gideon Stahlberg wrote: ‘A latent disease of the mind was slowly weakening the titan’s creative powers and sapping his ability … but one could still recognise that he was a great master; his play was almost more subtle than before and his art more remarkable’.

It was seen as a sign of his mental distraction that he seemed constantly disturbed by imaginary flies, though it has been postulated that this could have been caused by a condition called posterior vitreous detachment, which puts black floaters in the field of vision. So his artistry in the 1920s may have been held back by a minor optical ailment, rather than early symptoms of his eventual problems.

Rubinstein did withdraw from chess in the 1930s due to his declining powers, and in three more decades of life he played no serious games.

These game notes are also based on Stahlberg’s comments, modified by modern computer checks.

Rubinstein-Hromadka: Maehrisch Ostrau 1923; King’s Gambit

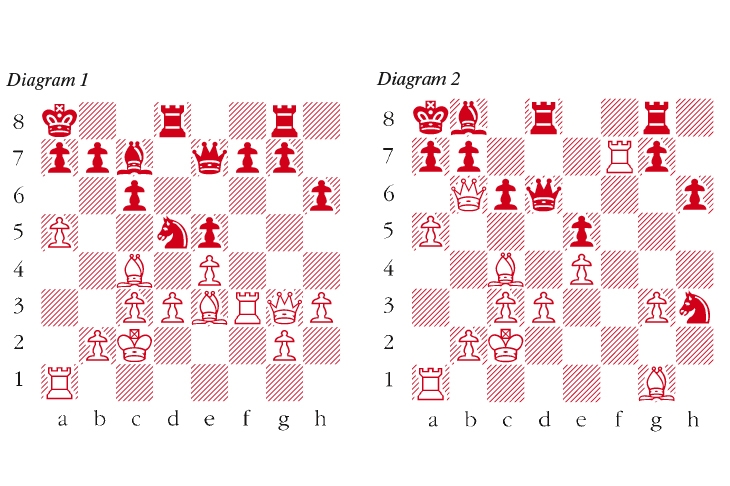

1 e4 e5 2 f4 Bc5 3 Nf3 d6 4 Nc3 Nf6 5 Bc4 Nc6 6 d3 Bg4 7 h3 Bxf3 8 Qxf3 Nd4 9 Qg3 Qe7 This was a popular line and it was well-known that 9 … Nxc2+ 10 Kd1 Nxa1 11 Qxg7 was very dangerous for Black. 10 fxe5 dxe5 11 Kd1 White gives up the right to castle but has compensation with the bishop pair and open f-file. 11 … c6 12 a4 Rg8 This is rather passive. 12 … Nh5 was more to the point. 13 Rf1 h6 Black is wasting far too much time and this gives White the opportunity to get organised for a queenside assault. Much better was 13 … 0-0-0 and if 14 Ne2 Kb8 15 Nxd4 Rxd4 with complex play. 14 Ne2 0-0-0 15 Nxd4 Bxd4 Black is again too compliant. He should prefer 15 … Rxd4 and if 16 c3 then 16 … Rxc4 17 dxc4 Qe6. White is certainly better but Black has definite practical counterchances. 16 c3 Black has wasted so much time that he essentially has no counterplay at all and White rolls forward on the queenside unimpeded. 16 … Bb6 17 a5 Bc7 18 Be3 Kb8 19 Kc2 Easily sidestepping the threat of … Nxe4. 19 … Ka8 20 Rf3 Nd5 (see diagram 1) A slightly desperate try. 21 Bg1 Sensible enough but 21 exd5 was also fine, e.g. 21 … cxd5 22 a6 (not 22 Ba2 e4) 22 … dxc4 23 axb7+ Kb8 24 Bxa7+ Kxb7 25 Qg4 with a winning attack. 21 … Nf4 22 Qf2 Bb8 23 g3 Preparing a brilliant combination. 23 … Nxh3 24 Rxf7 Qd6 25 Qb6 (see diagram 2) A pretty move and also the most incisive. If 25 … axb6 26 axb6+ Ba7 27 Rxa7+ Kb8 28 Rfxb7+ Kc8 29 Bc5 wins. 25 … Rd7 26 Bc5 Rxf7 27 Bxd6 Rf2+ 28 Qxf2 Nxf2 29 Bc5 Black resigns

Comments