Sometimes, it pays to rediscover what’s already under your nose. I’ve been umpteen times to the Natural History Museum but I don’t think I’ve ever seen it properly, not even at the evening parties I’ve been to under Dippy-the-Dinosaur, until now. I visited the new and refurbished Hintze Hall and it was a revelation. The thing that strikes most visitors is that there isn’t a dinosaur any more — Dippy is on tour — and he’s been replaced by Hope, who is a) a blue whale, b) female and c) genuine (the dinosaur was fake).

Swings and roundabouts. We have lost a dinosaur, but we’ve gained an entirely new perspective on an astonishing building, what a Times leader in 1881 called a ‘Temple of Nature’. What it does is remind us afresh of the genius of Alfred Waterhouse, and the profoundly Christian conception of the museum as a manifestation of the creative power of God by its founder, Richard Owen, a naturalist whose genius was matched only by his capacity for making enemies.

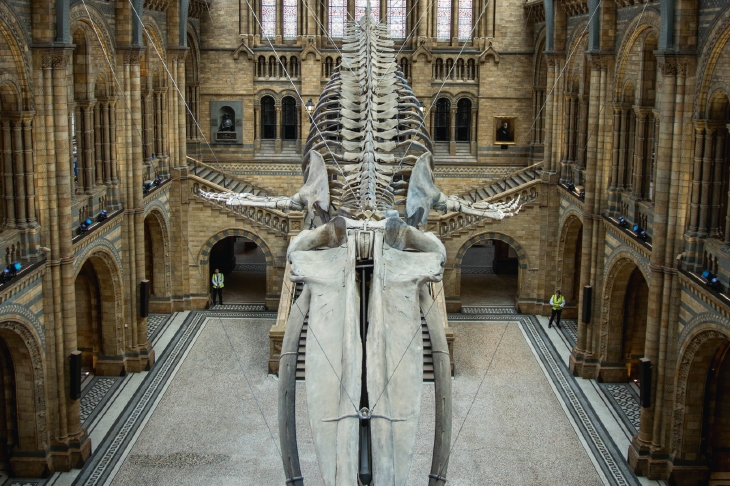

What the renovation of the great central hall has done is allowed us to see it properly, as effectively an ecclesiastical building. Hope-the-Whale has been winched into the ceiling, where her skeleton swoops down on her unseen prey. What that does is to clear the central space from the clutter around the dinosaur — except for some unfortunate information desks — and lift the viewer’s eye to the ceiling and the two upper galleries, with their forward-looking use of natural light.

Reader, it’s glorious.

The museum has been a victim of the old, hackneyed C.P. Snow idea of the two cultures; yet it’s visited by science people and families looking to keep the kiddies amused. Whereas the V&A across the road can be unapologetically beautiful, the Natural History Museum is for the people who don’t care about that sort of thing; they’re scientists, not aesthetes or religious. Indeed, I can remember a period when the curators seemed actually to be trying to escape from their captivating, purposeful building: you got white boxes for exhibits built inside the bays with their playful figures of creatures living and extinct. The buzz then was around the interactive Creepy Crawlies section, not the Victorian cases of stuffed creatures.

Well it’s a different story now. The new, clean design for the hall from Casson Mann means that you can properly see the triple-layered space and the cathedral-like nave with its Romanesque arches and grand staircase. There are ten new uncluttered Wonder Bays to tell the story of the evolution of life on the eastern side — meteorite to mastodon — and the diversity of present life on the west — insects to giraffes. Richard Owen, in his original conception, wanted easy access from the ‘specimens of existing to those of extinct animals’; in the central hall they face each other. (It’s pleasing that the next stage of the development will include a dinosaur park; Owen was responsible for the giant dinosaur figures in the Crystal Palace in Sydenham.)

He insisted that the museum, which was meant to spread over five acres, was to be a place for ugly creatures, not just spectacular ones, for the important thing was appreciating ‘the perfect fitness of the thing to its function’. He would have had a downer on the Instagram approach to exhibits. ‘As the purpose of a Museum of Natural History is to set forth the extent and variety of the Creative Power, with the sole rational aim of imparting and diffusing that knowledge which begets the right spirit in which all Nature should be viewed, there ought to be no partiality for any particular class merely on account of the quality which catches and pleases the passing gaze.’ He was also keen on evening openings, to give working people the chance to visit.

He would have been thrilled by the blue whale — celaphods were the first category in his plan for the museum: ‘one specimen, at least, of… the whale-kind should be prepared as an example of the power of the Creator as manifested by the hugeness of the creature’. In fact, Owen suggested it would be a warning of its possible extinction from new methods of slaughter; it could be the ‘sole and unique taxidermal evidence of this marvel of creation’.

The ecclesiastical character of the building was intentional; it was the Quaker Waterhouse’s fulfilment of Owen’s religious vision, specifically in the bold choice of German Romanesque, faced with terracotta, now cleaned and lovely.

Actually, the modern museum is a sort of cathedral, with Darwin enthroned on the grand staircase as its guiding deity. He should be replaced by Owen, returned to his old position overlooking the nave. This is his museum, a cathedral of creation.

Comments