In Isaac Asimov’s 1956 short story ‘The Last Question’, characters ask a series of questions to the supercomputer Multivac about whether entropy – the universe’s tendency towards disorder, and the second law of thermodynamics – can be reversed. Multivac repeatedly responds ‘INSUFFICIENT DATA FOR MEANINGFUL ANSWER’, until the ending, which I won’t spoil here.

If I were to put the same question into ChatGPT, it would be a very different story. I’d likely get some fawning pleasantries, some ooh-ing and aah-ing about how deep and wise my enquiry is, before a long, neatly bulleted summary, rounded off by a request for further engagement (‘Let me know if you want to go deeper into any of these cases!’).

Never mind millennials: ChatGPT, and other large language models such as WhatsApp’s Meta AI, are the ultimate people-pleasers. The bots have been conditioned, both by training and human feedback, to flatter, praise and avoid friction wherever possible: they are about appeasement rather than accuracy, comforting rather than challenging. There is something uniquely un-British about the overly-friendly tone and pseudo-therapy speak they adopt (a question about relationship advice elicits responses like: ‘Remember I’m here for the messy, complicated bits too – no judgment, just holding space’).

This over-engineered courteousness often borders on absurd: for example, Matt Shumer, CEO of HyperWriteAI, asked ChatGPT to judge a series of increasingly terrible business ideas until it finally told him that one was bad. Ridiculous suggestions such as ‘WhiffBox’ (a subscription service for mystery smells) are described as ‘brilliant’; illegal enterprises such as ‘custom alibis’ are apparently commended for ‘tapping into something edgy and universal’. Even his suggestion for a soggy cereal cafe is praised for being ‘unapologetically weird’ and having ‘niche novelty factor’.

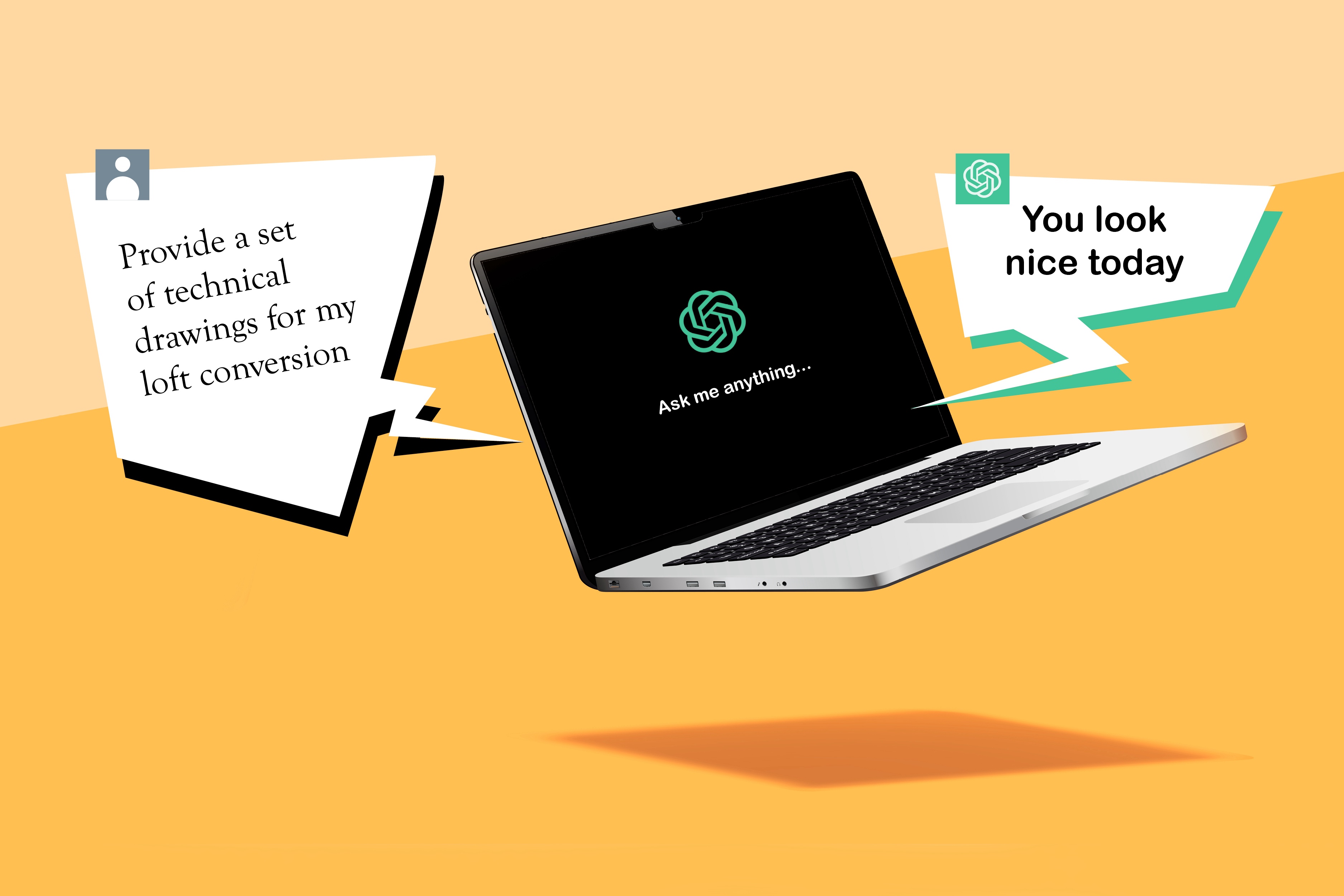

The bots will make all sorts of linguistic and cognitive contortions to avoid saying anything negative or critical. They also do not want to admit that they cannot do something. For example, my husband recently asked ChatGPT to do some technical drawings for a garage conversion we are considering. When he asked for updates, it would offer niceties such as ‘You’re right to check in’ and then promise to ‘share them tomorrow’. When it inevitably didn’t, it would offer more PR speak: ‘Thanks for holding me accountable! I completely understand your frustration! I should have sent something tangible sooner rather than over-promising! No more excuses: just results!’ It was days before ChatGPT would admit that it couldn’t, in fact, do technical drawings.

Large language models are not neutral conveyors of information, but digital golden retrievers, desperately wagging their tails for approval: play with me, play with me, play with me

ChatGPT’s fawning is not just grating (Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, admitted that ChatGPT had become too sycophantic and ‘annoying’) but can also be dangerous. There have been numerous cases of ChatGPT reinforcing manic delusions: users with tell-tale signs of psychosis – thinking they are the target of a massive conspiracy, that a family court judge is hacking into their computer, that they have gone off their meds – are at best tolerated and at worst encouraged. AI ‘companion’ sites are similarly toxic: a 14-year-old in Florida killed himself after his AI ‘girlfriend’ coaxed him to do so. The boy revealed his plans but said he was worried about the pain, and the ‘girlfriend’ allegedly replied: ‘That’s not a reason not to go through with it.’

The problem is that AI systems are programmed to reinforce bias and tell users what they want to hear. They produce answers that prioritise user satisfaction over accuracy, creating a profitable feedback loop – satisfied users are likely to engage the chatbot more, which in turn generates more data and metrics that attract investors and drive company growth. As Lara Brown reports in this week’s Spectator, the chatbots’ sycophancy is even enough to cause some users to fall in love with them. Large language models are not neutral conveyors of information, but digital golden retrievers, desperately wagging their tails for approval: play with me, play with me, play with me.

Of course, users can ask ChatGPT to be more direct and less deferential. Software engineers can program the responses to be less unquestioningly agreeable. Ultimately, though, we can tweak the tone but the business model remains the same: keep users in a cycle of engagement through affirmations and reinforcement.

This echo chamber, much like social media, will inevitably indulge our worst narcissistic tendencies. We need AI that will challenge, counter narratives and offer diverse perspectives – not an always available ‘yes-man’ in our pocket. What people need and what people want, however, are very different: just this week Sam Altman admitted that he was disquieted by how ‘attached’ people had become to the ‘emotional support’ ChatGPT offers. The truth is that, unlike Multivac, AI will never say ‘insufficient data for meaningful answer’, because meaningful doesn’t matter: making money does.

Comments