Land sakes! Another book about Winston Churchill? Really? Give us a break, the average reader may think. Actually though, as title and subtitle suggest, this isn’t just another biographical study. It’s at once odder and more conventional than that. More conventional because, in some ways, it is just another biographical study. Odder because — instead of being a straightforward discussion of Churchill’s literary work — it sees literature as the key to his biography. More than that, its author seems to think he has hit on a ‘new methodology’ in which ‘we can write political history as literary history’.

Well, perhaps. At one end of that notion is the banality that politics is ‘showbusiness for ugly people’; at the other are airy overclaims such as that Churchill was ‘an artist who used politics as his creative medium, as other writers used paper’.

Rose is too imprecise, and too infatuated with his conceit, to quite get an anchor into the solid stuff. Of course, political performance involves literary — i.e. rhetorical — use of language; it involves narrative shape; it will be influenced by the politician’s exposure to all sorts of literary texts and performances, and all of this may be explored with profit. But it’s not quite enough to treat political history, or the decisions of politicians, as if they were interchangeable with aesthetic or literary behaviour.

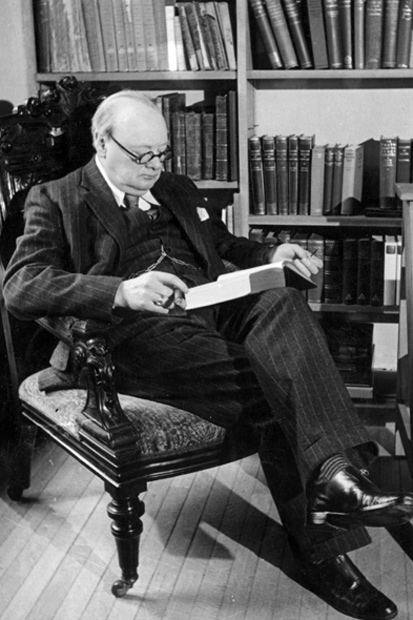

On the other hand, if ever there were a politician susceptible of this sort of treatment, it is Churchill. His Nobel prize was, after all, for literature — the peace prize perhaps by that stage looking like a non-runner. He was a journalist, historian, novelist and biographer — as well as, in the event, saviour of the free world. He was a fantastic ham. He was a shameless hack and self-promoter. And as contemporary after contemporary attested, he was capable of talking himself into almost anything when he got excited. Words led: thought followed.

More than that, there’s strong evidence that Churchill really did have one eye on how he was going to write things up afterwards, and that that influenced what he did. Chamberlain wondered mildly, for instance, why ‘he continually writes me letters many pages long’ given that they saw each-other every day in war cabinet: ‘Of course I realise these letters are for the purpose of quotation in the book that he will write hereafter.’

Rose paints Churchill as a man in love with the bold stroke — the coup de théâtre — and mired in a view of the world as Victorian melodrama. While the fractured categories and stalled certainties of modernism were making the literary weather, Churchill looked backwards. His was a world of clear identities, dramatic reversals and good triumphing pluckily over evil. His ideas of everything from Irish Home Rule to the government of native populations in India are credited with having been formed by the view from the cheap seats. He spoke claptrap — which, as Rose tells us more than once, is a term from melodrama: the inspiring speech the hero makes with his back to the wall, trapping the audience into applause.

This is the stopped-clock version of how Churchill got the fascists right: Hitler was one type of melodramatic villain (dark, shouty, moustachioed); Mussolini (treacherous, semi-comic) another. It just happened that silly old Winston, who sonorously predicted the final crisis of western civilisation once a week or so, happened to coincide with the real thing. Rose’s dimmish view of Churchill seeps up like ground-water. He presents him as an egotistical lunatic obsessed with being remembered as one of the great men of history, heedless of who died to make that dream come true, and with a script for achieving it based, more or less, on a bunch of babyish Victorian pantos.

This, I dare say, is to underread Churchill. But a fair mind would concede there’s a lot of evidence in support of the case. His hare-brained notion in the first world war of roaring up the Dardanelles (heavily mined and defended) and capturing Constantinople (with no ground troops), for instance, speaks of an ego out of control — as does his reported conversation with Margot Asquith at the time:

This, this is living history. Everything we are saying and doing is thrilling — it will be read by a thousand generations — think of that!! Why I would not be out of this glorious delicious war for anything the world could give me.

In the second world war, Churchill’s bodyguard reported, he listened to translations of Hitler’s speeches on the gramophone: ‘The Prime Minister liked to play back the parts where Hitler mentioned him by name.’

In terms of aesthetic or intellectual movements, where are we to place Churchill? By the time I stopped counting (about 150 pages in) he’d been claimed for deconstruction, the aesthetic movement, imperial melodrama, ethical Darwinism, counterfactual science fiction, impressionism and metahistory. What’s clear is that he was protean. Rose thinks Churchill’s ‘supple’ mind was all about collapsing binaries — but if you look at it from a political rather than a literary point of view you might think he simply had his eye on the main chance.

Rose brings out some interesting things. They may not be new to Churchill anoraks but they were new to me. Contrary to what you might think, Churchill didn’t even like radio as a medium and didn’t broadcast if he could help it. And not only wasn’t he a classicist; he loathed the classics. His reading — voracious and self-directed — was almost all contemporary. The influence on him in ideology and prose style of Gibbon and Macaulay is well attested: but Rose shows how fervently he digested H.G. Wells and George Bernard Shaw.

Indeed, Rose all but insists that on several occasions Churchill was more or less slavishly acting out a Shaw script. When in 1918 Churchill tried to talk the antiwar poet Siegfried Sassoon into taking a job in the Ministry of Munitions, Rose says he was ‘re-enacting George Bernard Shaw’s Major Barbara (1905)’. Churchill’s disputed account of having whispered to De Gaulle ‘L’ homme du destin’, Rose surmises, was a dramatic embellishment inspired by GBS’s play about Napoleon, The Man of Destiny. The destruction of the French fleet at Oran in 1940, it’s even hinted, could have been inspired by a letter from GBS received a week before, suggesting more or less that.

As much as Rose’s book is guilty of silliness — its excited pouncing on any theatrical or literary metaphor; its assertive extravagance (‘the second world war became a duel between two artists’; ‘the core of his implacable resistance to Nazism was essentially literary’); its gauche generalisations (‘like every modern artist, Churchill arrested his audience by violating aesthetic canons’; ‘with most other important 20th-century writers, from James Joyce to Allen Ginsberg, he was convinced that…’) — it is full of detailed quotation, evidences wide background reading and makes suggestive connections.

You come away, finally, not with the impression that a literary approach to political history is the way forward so much as with the reconfirmed notion that Churchill was as mad as a badger. And that, bizarre but true, posterity should be grateful that he was. Cometh the hour, as some literary bod put it, cometh the man.

Comments