They do things their own way in Liverpool; they always have. In 1997 the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra launched a contemporary music group called Ensemble 10:10 (the name came from the post-concert time-slot of their early performances). For a decade now, they’ve also administered the Rushworth Prize, an annual competition for young composers based in the north-west. And while classical fads and crises have come and gone, the RLPO has held its friends close and tended its garden. The result? The kind of artistic self-assurance that lets you put your chief conductor in charge of a première by a novice composer, and then call in a Barenboim to guarantee a full house.

It’s hard to imagine a piece like this winning a major prize two decades back

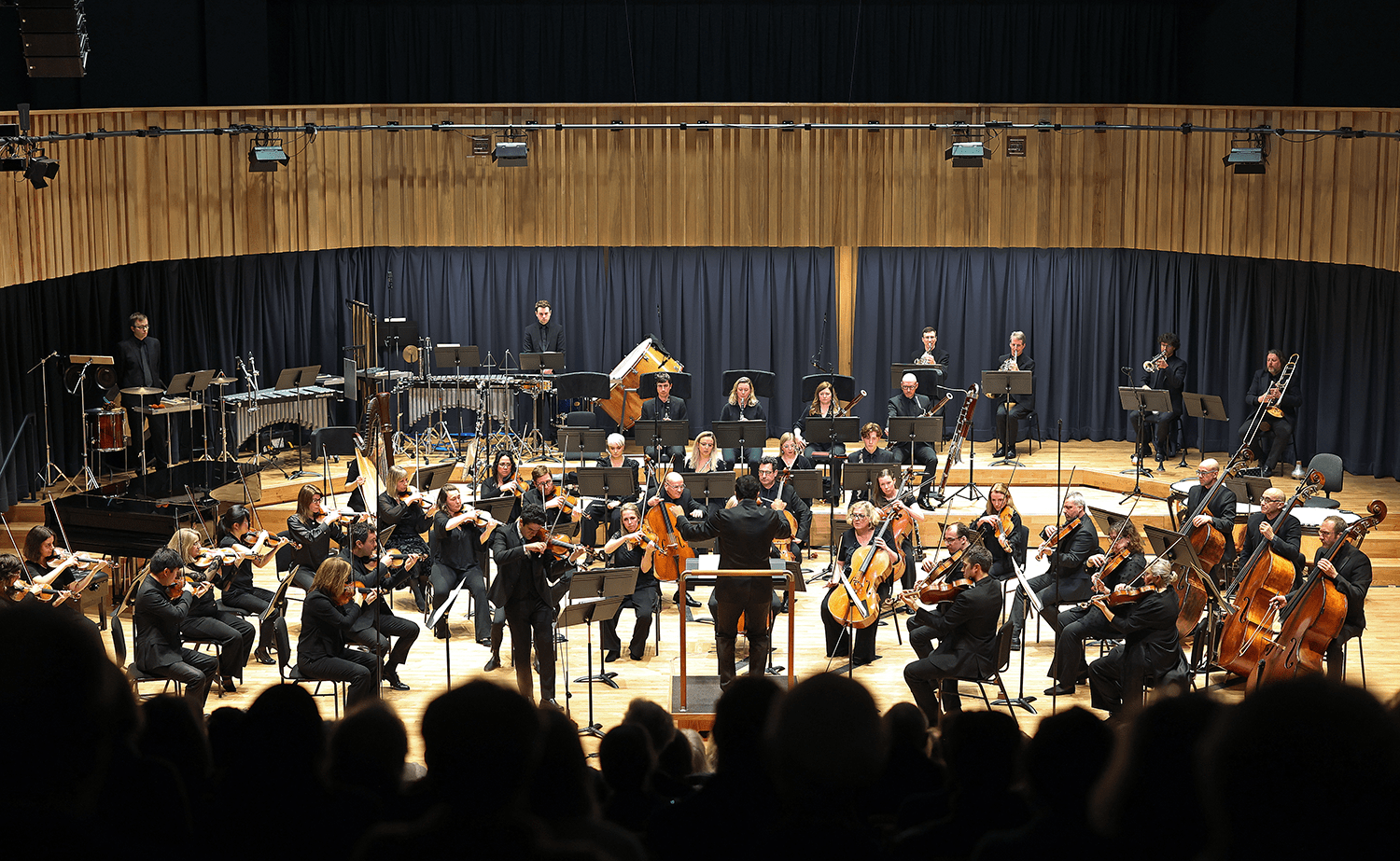

At any rate, that’s what they did last week, when Ensemble 10:10 premiered Danu’s Rhapsody by the 2023 Rushworth Prize winner Sam Kane. No apologetic pre-concert slots here; no fobbing off with an assistant conductor. When Liverpool picks a winner, it goes all in. This was a main season première, with a 44-piece ensemble and Domingo Hindoyan conducting. Michael Barenboim was the violin soloist in the other two works in the concert: Kareem Roustom’s 2019-vintage First Violin Concerto and – 100 years old, but still the toughest nut on the programme – Berg’s Chamber Concerto.

Kane’s piece surprised me; in fact, his programme note was startling enough. Danu is an Irish nature-goddess, who ‘encounters mythical creatures and dances with the forest’s faeries’. It could almost be a Bax tone-poem – one of those lush Celtic fantasies like Tintagel or The Garden of Fand. It sounded a tiny bit like Bax, too, but in a good way. Clarinet melodies sloped like shadows between leafy murmurs and the violins struck up a whirling reel. It all moved towards one of those crowning, gorgeously tinted orchestral sunsets that we’re supposed to think went out of fashion somewhere around 1918.

But we’re not obliged to think that way, and Kane – a recent graduate of the Royal Northern College of Music – clearly feels under no compulsion either. Interesting, that. It wasn’t so long ago that you’d hear of composition professors dismissing romantic scores like Kane’s as ‘film music’ (the use of the term as an insult speaks volumes). Certainly, it’s hard to imagine a piece like this winning a major prize two decades back, and it’s still quite hard to imagine it happening anywhere less secure in its own judgment than Liverpool.

This – to be absolutely clear – is a criticism of norms in contemporary classical music, not of Kane’s composition. The charm of Danu’s Rhapsody – apart from its warm pictorialism and frank appeal to the emotions – lies in Kane’s ease with classical harmony. Towards the end, you felt a tug towards the final resolution (it actually had one) in a way that Mozart or Mahler would have recognised. There’s no one way to write new music but Danu’s Rhapsody wouldn’t sound out of place on Classic FM, and if it made their playlist it’d be in the Hall of Fame within a year. Again, I probably need to make it clear that this is a compliment.

Meanwhile, there was the Berg – in which Hindoyan liberated vivid, unquiet colours while maintaining a hands-off approach to his two soloists, Barenboim and the (formidable) pianist William Bracken – and the Roustom concerto, which bustled along with Stravinsky-like vigour, dappled with sunlight. Barenboim is clearly a thinking violinist, an impressive technician with a broad palette and a reserved platform manner. Hindoyan, sensibly, took him as he found him, and gave him space. The audience was wholly on side, and at the end of the Berg there were cheers.

On the previous night, the Pavel Haas Quartet had returned to the Wigmore Hall, and there’s another ensemble that isn’t short of self-knowledge. The individual players in this youngish Czech group are all formidable virtuosos. But they inhabit a different psychological world from the hot-house atmosphere of famous 20th-century ensembles like the now-disbanded Alban Berg Quartet, or the Borodin Quartet (who claimed to have signed their first contract in blood). There’s air in their sound, and no sense that any member occupies a subordinate position.

In practice, that meant clarity and colour in the two modernist Czech works that formed the first half of the concert – Schulhoff’s sardonic Five Pieces of 1923, and Martinu’s Fifth Quartet. Simon Truszka’s viola playing brought woodsmoke and earth tones even to music as determinedly urban as Schulhoff’s fourth piece, a sort of transfigured tango. After the interval, the pianist Boris Giltburg joined them in Brahms’s C minor Piano Quartet, and he seemed to match them from the off. They brooded, they raged; they were tender without sentimentality. Is this Brahms’s greatest chamber work? The Horn Trio and the Clarinet Quintet might have something to say about that. But on this occasion, it certainly felt like it.

Comments