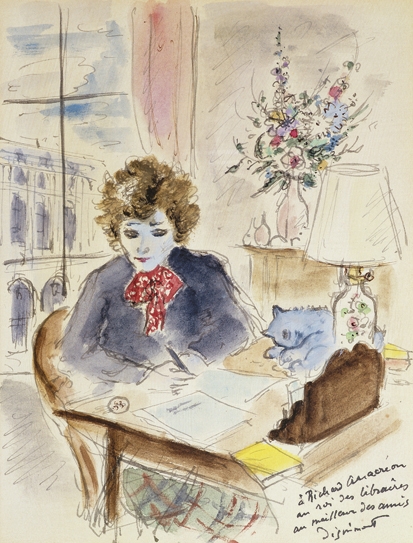

Monstrous innocence’ was the ruling quality that Colette claimed in both her life and books. Protesting her artless authenticity, she was sly in devising her newspaper celebrity and ruthless in imposing her personal myths. She posed as provincial ingénue, wide-eyed young wife of the Paris belle époque, scandalous lesbian, risqué music-hall performer, novelist of prodigious output, theatre reviewer, beautician, seducer, the most feline of cat-lovers and, ultimately, garlanded literary lioness.

Yet her phoniness should not deter people from reading her books. Although most of her work resembled an imaginary autobiography, it was never self-obsessed or constricting. On the contrary, she used her fictionalised self as the centrepiece of a worldly comedy with a cool, sane vision which skewered the moralising humbug of the Third Republic and lampooned a patriarchy of pompous, empty, third-rate men. She is playful, teasing, supple; full of gaiety and zest; and an exquisite stylist, so rich and simple, exact and clear, perceptive and shrewd. Rereading her, one finds that her creed of sexual and emotional fulfilment has scarcely dated. Her dialogue remains as crisp and suggestive as ever. The air of audacity has not staled, even if the lovers’ anguish seems contrived. And always she remains a glorious, lyrical observer of natural beauty.

Colette — Sidonie-Gabrielle Colette — was born in 1873 in the wooded, charcoal-producing area of Burgundy, far from the fashionable vineyards. Her charming, defeatist father had been invalided out of the army after his leg was amputated. Her lively, clever mother took Corneille’s plays to read in church under cover of a prayer-book. The family’s dwindling finances catapulted Colette into marriage at the age of 20 to Henri Gauthier-Villars. This rascal had a stable of poor hacks — known as nègres — who churned out journalism and novels which he published as his own work under the nom de plume of Willy. Colette was press-ganged into the nègres, and under Willy’s control, locked in her room, wrote six phenomenally successful autobiographical novels with such titles as Claudine à l’ecole (1900) and Claudine à Paris (1901).

She broke away from literary slavery, and from the subjugation of an odious marriage, in 1906. Thereafter she set herself against the duties, prohibitions and guilt imposed by men, and supported herself as a mime artist, dancer and music-hall performer. Her first lesbian affair — encouraged by her husband — had occurred in 1901 with ‘Georgie’ Raoul-Duval, as described in Claudine en ménage (1902). She was the lover in 1905-10 of Mathilde (‘Missy’), the butch daughter of the Duc de Morny, Napoleon III’s half-brother, who had died of an overdose of aphrodisiacs.

No one who makes such a profession of authenticity, directness and candour is likely to be straightforward. The courtesan-novelist Liane de Pougy, who had an inveterate dislike of Colette, wrote in her Blue Notebooks of ‘her insincerity, her affectations, her talent, her infernal spite’. Certainly, the author of Chéri and of Gigi was premeditating, ambitious, untrustworthy and status-conscious — as well as great fun.

Her self-serving is evident in her celebrated novel La Vagabonde (1910). Its narrator, Renée, part of a theatrical troupe touring provincial France, is tempted to marry rich, lovable Maxime Dufferein-Chautel, but rejects conformity and security in order to follow her precarious quest for individual fulfilment. The novel is a compensatory rationalisation composed by Colette after she failed to coax a department-store heir to marry her.

Instead, in 1912, she married a radical politician, Baron Henri de Jouvenel. Eight years later, she began an affair with her 17-year-old stepson, which lasted for years. Finally, in 1925, she met a young dealer in pearls, was captivated by his ‘satanic charm’, and married him. She had a troubled time during the German occupation, for her husband was partly Jewish. Overweight, crippled by arthritis, she was latterly cloudy in her mind.

There is an affably personal touch to Jane Gilmour’s book. During les evénéments of 1968, she worked in Paris on a doctoral thesis about Colette. Returning to her native Australia, her career took other directions; but in retirement she returned to Europe to refresh her research and write Colette’s France. The book is gentle and affectionate, prettily illustrated, without the austerities of academic analysis, and will make amiable holiday reading for visitors to France. It narrates Gilmour’s visits to the landscapes and homes that meant most to Colette:

A bit of Burgundy, a few corners of Paris, two or three cantons in the Jura and Franche-Comté, stretches of flaxen coast in Picardy and Brittany, the green meadows of Brive, the glowing red heath of the Corrèze high plateau, and lastly Provence.

An appendix provides advice for those on the trail of Colette’s heritage: Paris restaurants identified with her, bosky villages where she strolled, the shop in Saint-Tropez where she always bought her sandals.

Comments