It’s a critic’s job to pick holes in the dafter aspects of opera productions, but in truth audiences are usually capable of detecting nonsense when they see it. ‘She must be at least 150,’ commented the gentleman sitting behind me, referring to the wheelchair-bound old lady who was trundled on stage at the start of Northern Ireland Opera’s new production of Eugene Onegin, and then parked there, pretty much for the duration.

It really buzzed along, even if the set resembled a public lavatory (urinal chic seems to be an emerging trend)

He had a point. Was she meant to be an elderly Tatyana? Then why was she dressed in modern clothes when the rest of the action played out in the era of Pushkin? Why had she been abandoned in a derelict warehouse (superbly realised, complete with breezeblocks, water stains and metal ducting)? What were her carers doing, when they weren’t inserting themselves into the choreographed crowd scenes? And why hadn’t the poor old dear’s family reported them to the official watchdog?

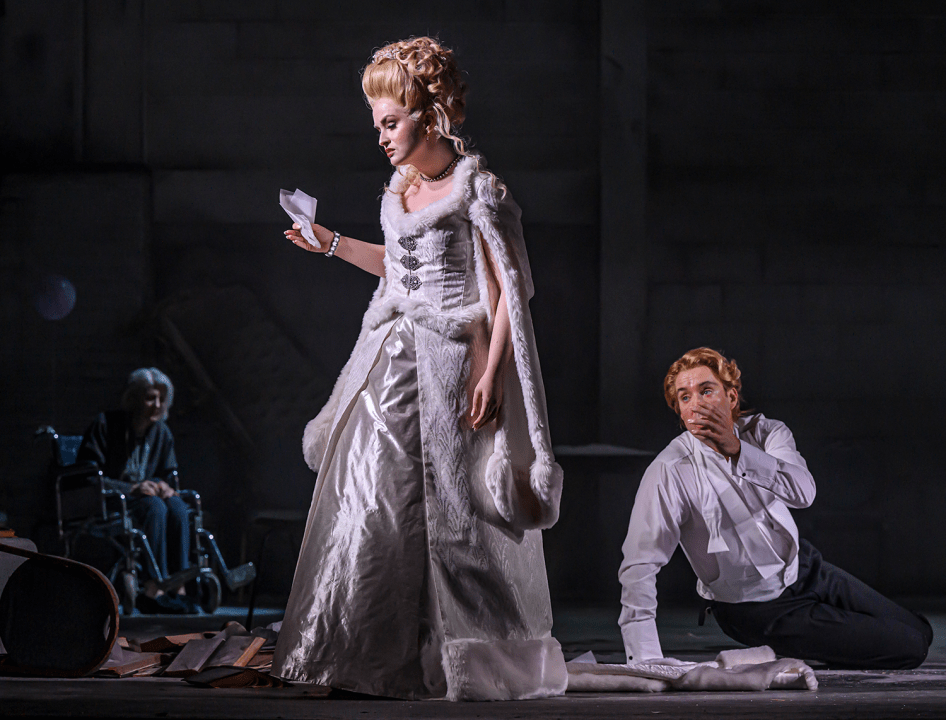

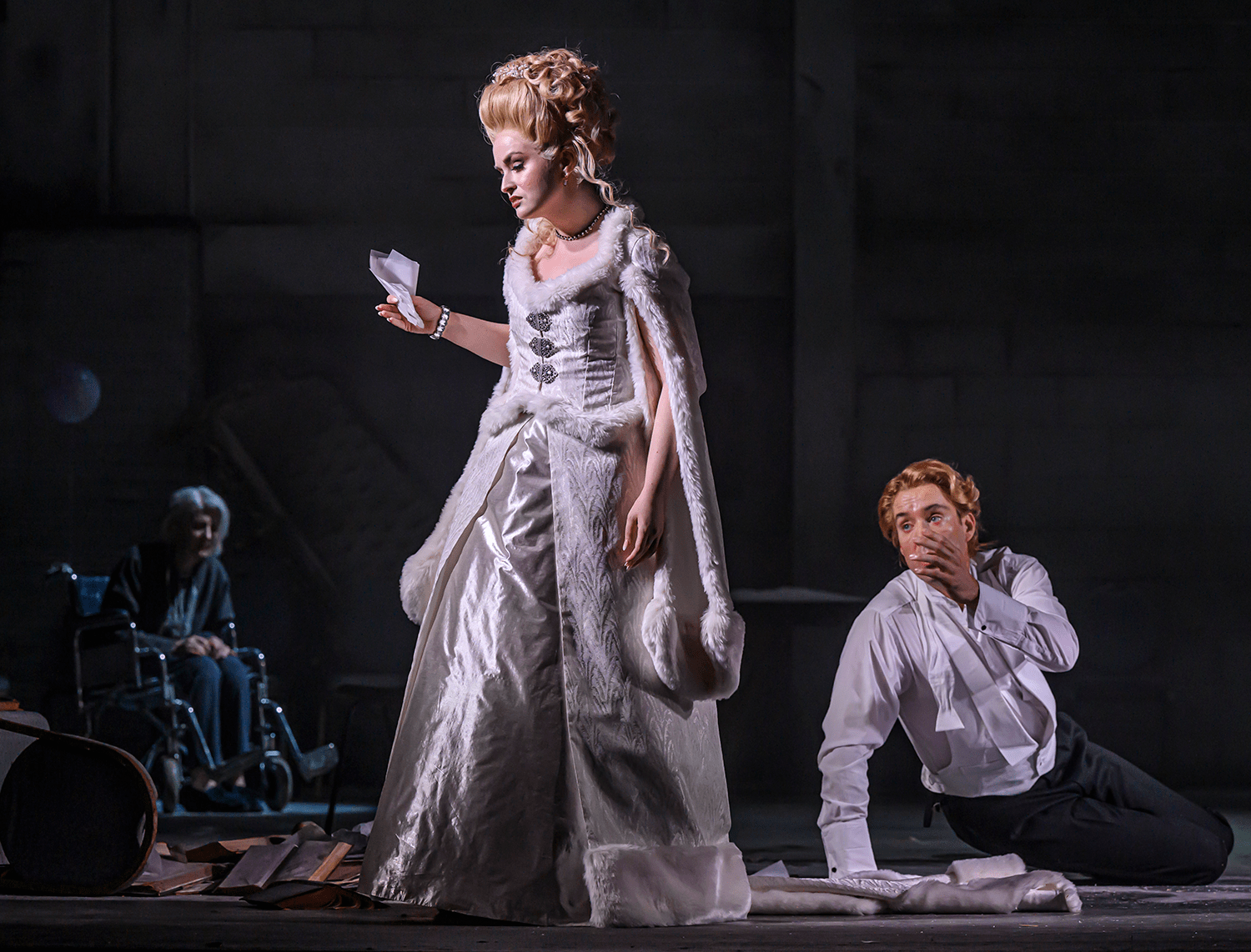

So many questions, so few of them having anything to do with Eugene Onegin. True, the opera deals with the sorrows of youth as perceived through the eyes of experience, but Tchaikovsky already provides senior viewpoints: Madame Larina, Filipyevna, Prince Gremin. Further layers are superfluous, and at worst (as happened here in Tatyana’s letter scene) they’re an outright distraction. Obviously, there’s no definitive way to stage an opera: what matters is whether the director’s concept opens up the drama’s possibilities, or closes them down. This production by NIO’s artistic director Cameron Menzies – or at least those aspects of it, the old lady and the empty warehouse – seemed to do neither.

That was a pity, because this Tatyana (Mary McCabe) was particularly touching; impetuous and shy in the early scenes and singing with a lovely mixture of fragility and ardour. Bizarrely, within the industrial setting everything played out more or less as a traditional production of Eugene Onegin, barring those negligent careworkers and the business of dancing awkwardly around the piles of rubbish on the floor. There were lively stylised ballets, and some genuinely intriguing ideas: Menzies turned the peasants’ choruses into vaguely menacing pagan harvest rites.

Yuriy Yurchuk was a strapping Onegin with a firm steely voice; and Norman Reinhardt was almost his match as Lensky, delivering his big pre-duel monologue with unnerving, slightly squally, force. It was conducted in broad brushstrokes by Dominic Limburg, and it should be said that whatever the merits of Menzies’s direction, the production values were as high as you’ll find anywhere in the UK. This looks likely to be NIO’s only full-scale production this season and the company’s commitment was beyond question. Even – no, especially – the granny. The actor, Anne Flanagan, could hardly have embodied her wordless role with more presence, or patience.

In Cardiff, the chorus and orchestra of Welsh National Opera leafleted the audience as they arrived for the opening night of the new season – protesting for their livelihoods in the face of funding cuts from both Welsh and English Arts Councils. The opera was Rigoletto – a new staging by the company’s artistic director-designate Adele Thomas – and the curtain rose on scenes of bum-fighting and dry-humping from the bouffant-wigged denizens of the court of Mantua, who appeared to have been dressed (man-kilts and bare chests) by Jean Paul Gaultier. Imagine a perfume advert created by an angry, horny sixth-former, and crowned by the arrival of a grisly-looking hog roast. You can probably guess what happened to its head. Edgy stuff – if decade-old midwittery (the programme book references Cold War Steve) is your bag.

Put that aside, and there was an undeniable manic energy about Thomas’s production; a universe just one notch short of hysteria where all smiles are grimaces, arms semaphore wildly and Gilda (Soraya Mafi) spins and bounces like a hyperactive toddler. Set against the pacey, deep-hued conducting of Pietro Rizzo, it really buzzed along, even if the set resembled a public lavatory (like superfluous crones, urinal chic seems to be an emerging trend in opera productions). And there’s no arguing with a Rigoletto as volcanic and as richly textured as Daniel Luis de Vicente. The Duke (Raffaele Abete) stood little chance against him.

But really, it was Mafi’s night. She’s long been an excellent singer; but as Gilda she hit new heights – fearless, impulsive and vulnerable, but always glowing. As a foil for Luis de Vicente, Mafi was desperately moving; she lit the Act Three quartet from above and in ‘Caro nome’ she spun delicate, tumbling vocal lacework that glinted and shone against the drama’s thunderous skies. Perhaps the ovation she received was heard at the Senedd (it’s right next door, after all) where, in the wake of brutal arts cuts, they’ve nonetheless found the cash to stick another 36 members on the public payroll. Less culture, more politicians: that’s what we voted for, right?

Comments