The slow but certain conquest of all public life by those promulgating the politics of identity has achieved a new victory in the realm of classical music. Cloaked in claims of benevolence and good intent, it arrives as a divisive force, screaming equality but in reality delivering nothing of the sort.

Much of our public discourse is focused on identity politics. Our news cycle is replete with tales of gender pay-gaps, unmet inclusivity quotas and the great struggle for the elusive goal that is equality, so perhaps it should come as no surprise that we now find these issues played out in the classical music industry. The dark heart of all this is to be found in the (sadly) niche area of contemporary classical music. Of the numerous competitions and schemes on offer for composers in Britain, a disturbing number contain politically-driven caveats as part of their application process as a means of realising the great idée fixe of our time, ‘diversity’. The most startling example to have emerged recently is from a joint venture by the Centre for New Music at Sheffield and Sheffield University, offering young composers the opportunity to have their music workshopped and recorded by the Ligeti Quartet. Nothing to see here, officer. That is until you scroll further down the page and discover the competition’s curious ‘two ticks’ policy:

‘A “two ticks” policy will be in place for female composers, composers who identify as BME, transgender or non-binary, or having a disability, to automatically go through to the second stage of the selection process.’

It’s difficult to know where to begin with this. For a start, the policy is staggeringly patronising to the composers who belong to these groups. What should be an incidental fact about someone’s person now takes precedent over their craft. Composers who happen to belong to one of these select groups are given a pat on the back and a snide helping-hand by virtue signallers of the worst kind. They are not valued for their artistic endeavours, the time and effort they have put into their work. Instead, they are trotted out by the diversity apparatchiks as a means of showcasing how wonderfully compassionate, forward-thinking and fluffy they are. Composers should be incensed that their music is forced to take a back seat to their race, gender etc.

Then there is the curious pick’n’mix quality of the minority groups included. Presumably gay composers have not made the cut here as their contribution to classical music is already seismic relative to their numbers. Apologies to white working-class composers who are most definitely under-represented in classical music, and for whom ‘white privilege’ seems to have had very little sway. Apologies also to religious minorities who haven’t yet received a free-pass. Helping people from disadvantaged communities gain access to classical music education is admirable, but it requires hard work at the ground level. The cheap tokenism exhibited by CeNMaS and Sheffield University is, at best, useless in addressing these issues. A good start would be overhauling music education in schools, throwing out the ukuleles and exposing all children to the glories of classical music.

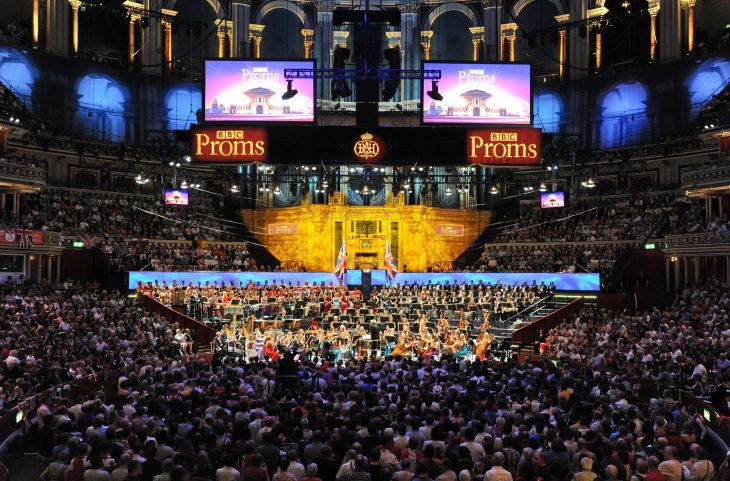

The BBC Proms is the latest to jump on the quota bandwagon. In keeping with current fashions, it has committed itself to a 50/50 gender split among the new composers the festival showcases by 2022. Other classical music festivals have made similar pledges, the Cheltenham and Aldeburgh Festivals being notable examples. These developments have been set in motion by the PRS Foundation’s ‘Keychain’ initiative, which has campaigned for equal gender representation at music festivals: its stated aim to ‘accelerate change and create a better and more inclusive music industry’. Current orthodoxies have rendered any dissenting views on this change strictly heretical, and so almost all the coverage of the news has been positive. To question whether having a gender quota at music festivals is necessarily a great leap forward is to reveal yourself a terrific misogynist if you are a man or else simply naïve if you are a woman. However, there are several problems with the Proms’ 50/50 pledge that should not go unmentioned.

The introduction of a quota for female composers implies that there is virulent sexism within the management of the BBC Proms, in turn advancing the narrative that there are countless talented female composers whose music is not being heard due to legions of patriarchs who wish to keep them out. Anybody who has had any experience inside the classical music industry, and is being honest, cannot truly claim institutional prejudice exists. There may be individual prejudices, but that is quite different from the argument that the entire industry is a hotbed of bigotry.

Part of the trouble is that you can profit greatly by saying there is a problem with sexism – and suffer for refuting it. It would have been refreshing to see David Pickard, the director of the Proms, defy the campaigners and say ‘we select our composers solely on the merit of their music, regardless of gender’, but of course he didn’t. Instead, he told us that

‘Achieving a 50/50 gender balance of contemporary composers performed at the BBC Proms is something we have been committed to for some time and consider vital to the creative development of the world’s largest classical music festival.’

Pickard has taken the easy option, vindicating those who argue that institutional prejudice exists. It is difficult to blame him, though, when the consequences of opposing the diversity lobby often involve having your character entirely discredited and a curtain drawn on your career. The fear of reprisal allows these fallacies to gain traction even when they are clearly false.

The quota-based approach to music festivals will inevitably mean that quality begins to take a secondary role. Those who argue in favour of quotas shy away from this obvious side-effect of their policy which ultimately places group identity above all else. If there are six worthy male composers and four worthy female composers, under the Proms new policy one of the men will be axed and replaced with a woman. Vice versa, and the same logic applies.

People who are familiar with contemporary classical music events know that audience numbers are often on a par with those found at the preliminary rounds of a regional curling championship, so to sacrifice the quality of contemporary music at the world’s best attended classical music festival, in which new works are placed alongside favourites from the canon, seems decidedly short-sighted when it comes to recruiting new audiences.

Perhaps the most depressing aspect is that many will disagree with these changes in private, but feel unable to speak out for risk of losing their jobs, funding, opportunities etc., such is the madness of the climate. ‘I know, it’s ridiculous!’ people will say in confidence, ‘… but don’t tell X that I said that!’ is a conversation many of us have had. I know people who will keep their views hidden even when speaking to others with whom they agree, not unlike the fearful subjects of some totalitarian regime. We should not, however, be scared to air these opinions when we know they are not founded in sexism or bigotry, but from the principle of meritocracy and above all from a love for the music. I suspect that those who are against the politicisation of classical music and clumsy attempts at social engineering are in fact the majority, though we may never know unless people find the confidence to speak up.

We shouldn’t underestimate the danger of this sort of agenda, even if we consider contemporary classical music to be only a small dot on the cultural map, far from the white heat of rioting in Charlottesville and transgender bathroom debates. It belongs to the cultural battle of this generation: group identity vs. the individual. The former seems to be winning out, and more people need to speak out on these issues. If it turns out that Brahms enjoyed putting on lipstick, slipping into Clara Schumann’s petticoats, and referring to himself as Mrs Brahms, this would neither heighten nor limit my enjoyment of his Second Piano Concerto. It’s a great work of art – and that’s all that should matter. We should fight back against the encroachment of identity politics into classical music, and indeed everywhere else, before we are all just categories on a Sheffield University diversity management form.

Philip Sharp is a pianist and junior fellow at the Royal Northern College of Music. A version of this article was originally published on the Sharp on Culture site.

Comments