Another Country: London Painters in Dialogue with Modern Italian Art

Estorick Collection, 39a Canonbury Square, London N1, until 20 June

In recent years there has been something of a vogue for encouraging contemporary artists to respond to particular works by artists of the past, and to make paintings as part of that response. The prime example of this curatorial trend was Encounters: New Art from Old, staged by the National Gallery in 2000, and including such painters as Balthus, Patrick Caulfield, R.B. Kitaj, Cy Twombly and Euan Uglow. The exhibition featured a number of bizarre pairings (Uglow and Monet was one) and some highly fruitful ones, such as Leon Kossoff with Rubens, but the thrust of the show involved new work being produced around a specific painting in the National’s collection. The Estorick’s fascinating exhibition is less prescriptive than that.

The idea for the show comes from Lino Mannocci (born 1945), an Italian painter resident in England since 1968, with something of a reputation as a mover and shaker in artistic circles. An able writer (he compiled the catalogue raisonné of Claude’s etchings), Mannocci also curates exhibitions. He is the leading light of a group of artist friends who are bound together by no ties of style or belief, but share a commitment to reinterpreting figurative painting for the 21st century. The current excursion is not the first time this group has exhibited together — in 2007 they showed in Bergamo, and there have been other related displays. The idea of a circle of painters being mutually supportive is an appealing one in this self-serving and competitive world, and it is even more gratifying to discover work of so high a calibre being so equably and informally offered to the public view. Congratulations to all concerned.

Ten artists arrayed over the two smallish ground-floor galleries of the Estorick means that the works of each one are inevitably few and carefully selected. The first thing to notice is that this is not necessarily new work, made in response to the artists featured in the Estorick’s permanent collection. It seems rather to consist of examples chosen from each artist’s recent output which might in some way be relevant. In some cases the relationship between present and past is somewhat tenuous, but the enthusiasm of the exhibitors is clear from an exceptionally useful catalogue. This well-illustrated paperback (price £9.95) has a thoughtful and wide-ranging introduction by Brendan Prendeville, and an essay by each artist. All are interesting, but among the best contributions are Mannocci on metaphysical painting, Arturo Di Stefano on Morandi, Luke Elwes on Zoran Music, Timothy Hyman on Sironi and Alex Lowery on Filippo de Pisis.

It’s always interesting to read artists discussing other artists, for what it reveals about both parties, and for the professional insights to be had. This publication deserves a long shelf-life after the exhibition closes, but the show itself merits our attention. So many public galleries display only the currently fashionable that it’s a refreshment for the spirit to find a museum prepared to show serious figurative artists in mid-career. In the first gallery the visitor is greeted by the paintings of Luke Elwes (born 1961), tidal drifts of marks moving against firmer statements like breakwaters, imagery that doesn’t strike so much as insinuate and return. ‘Trace’ is vertically striped like a flag and appears to be rippling in the wind, yet is also a hillside worn and abraded by the elements.

Next comes Mannocci, with his mysterious spaces composed of subtle colour and intermittent brushwork, featuring the angel of the Annunciation appearing in a chamber, or a tiny figure seen against a great wall which is also the sea. Opposite is Glenys Johnson (born 1952), with colour edging into her monochrome cityscapes. Look at ‘Broadgate 1’, a building site with blues and reds rubbed in to articulate or dissolve the structure. Next to her hangs work by her husband Tony Bevan (born 1951). He has chosen Morandi for his artistic interlocutor, and the large ‘Table Top’ painting he contributes makes an intriguing parallel with Morandi’s obsessive still-life compositions. Bevan’s painting is as if drawn with shards of terracotta and burnt matches, leaving manifest traces on the canvas. Beside the exit, there’s an exquisite small monochrome by Johnson called ‘Emerging Church’, which was inspired by a site in Russia flooded for some civic project, but where the waters were receding and the buildings re-emerging.

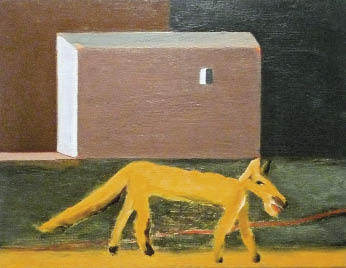

There’s no room to mention every artist, but in gallery 2, the eye is at once taken by Alex Lowery (born 1957), poet of the Dorset coast, and particularly of West Bay and Portland, seen here in very blocky almost abstract profile. Next to him is a large dramatic painting, ‘Arcades, Bologna’ by Arturo Di Stefano (born 1955), in which the artist’s interest in surface texture is intriguingly at odds with the pictorial space — not describing it but contradicting it, and in the process setting up an interesting push-pull dynamic. A trio of London self-portraits by Timothy Hyman (born 1946) are witty and rather moving, and the room ends with Andrzej Jackowski (born 1947), a painter of mythical subjects with disorienting settings, in which tower blocks look like radiator grilles, and the self wails like a demon lover.

Upstairs there are two more floors of galleries containing highlights from the Estorick’s permanent collection, some of which relate to the show downstairs. There are fine Sironis, including a dark ‘Urban Landscape’ (c.1924), and Marino Marini’s ‘Quadriga’ bronze. On the top floor is a room of Morandi’s etchings and drawings, and another room containing four paintings by that great neglected master Zoran Music, with a couple of works by his wife Ida Barbarigo. All the artists’ enthusiasms are represented, except for Lowery’s de Pisis. I’m not sure how much light the upper galleries cast on Another Country, but they are nonetheless worth a visit.

Comments