In W.B. Yeats’s ‘Meditations in Time of Civil War’, a testing allusion emerges amid a scene of nightmare:

Monstrous familiar images swim to the mind’s eye

‘Vengeance upon the murderers,’ the cry goes up

‘Vengeance for Jacques Molay.’

More about de Molay, last master of the Knights Templar, can be found in Dan Jones’s new blockbuster on the crusading order, along with quite a few monstrous familiar images. Jones states from the outset his noble intention: to write ‘a book that will entertain as well as inform’. In this he has hitherto had great success; his two spectacular chronicles, The Plantagenets and The Hollow Crown, traced that dynasty from the White Ship to Bosworth Field, and threw in some Tudors for good measure.

He now tackles ‘the most famous military order in the world’, whose two-century history occupies a stage that stretches ‘from Dublin to Famagusta’. A history of the Templars is necessarily also one of the crusades — which Jones cannily makes topical. He points out that his story involves ‘a seemingly endless war… where factions of Sunni and Shia Muslims clashed with militant Christian invaders’; and he emphasises ‘the relationship between international finance and geopolitics’ and ‘the power of propaganda and mythmaking’. Once flagged, however, such correspondences are left mercifully implicit.

The Templars were formed in 1119 with the unimpeachable aim of protecting pilgrims on their way to Jerusalem, which had been reclaimed for Christianity two decades earlier by the first crusade. But their modest beginnings were very soon left behind; the legend that for the order’s first nine years it constituted only nine knights is, Jones writes, ‘romantic and numerologically pleasing, but false’. The requirements of the newly won Frankish possessions in the East, and the certainty of St Bernard of Clair-

vaux — his era’s greatest preacher, though not very attractive to posterity — that soldiers of God might ‘kill the enemies of the cross without sinning’, ensured the order’s rapid growth in numbers, power and (thanks to numerous privileges granted by the Pope) riches without equal in Europe.

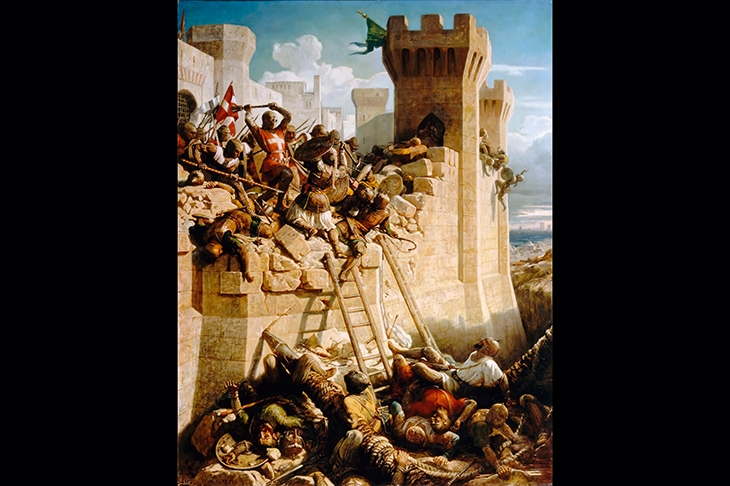

What follows is a long, bloody and downbeat narrative, which seems to dampen the spirits even of this gung-ho historian. For the fact is that the Templars, whether as heroes of legend or villains of conspiracies, have a disappointing record. From the second crusade in 1148, to the fall of Jerusalem in 1187, and on to the final disaster at Acre in 1291, they were always prone to strategic calamity. Jones musters the odd dry line — the siege of Damascus is summed up as ‘a four-day hack through a booby-trapped fruit field’ — but the drier vastness of desert and defeat overpowers him. The Templar masters are dutifully named, but they rapidly perish. Gerard de Ridefort is a possible exception, but only achieves humanity through a sort of dark comedy: he repeatedly advocated suicidally stupid attacks, but somehow survived to command the next one.

It all gets too much even for Jones, and he starts to muddle up the queens of Jerusalem, a venial sin for anyone other than a narrative historian of the crusades. By the time Richard the Lionheart and the Emperor Frederick II make their morale-raising appearances, Jones is in need of relief at the ramparts. These stories have, after all, been often told before, and his own repetitive phrases are revealing. We hear that ‘what the English king lacked in punctuality, he made up for in personality’; and a little later that ‘what Frederick lacked in physical stature, he made up for in personality’.

But just as hope is fading, Jones blazes out enough personality to roast the reader, delivering a fresh and pithy account of that vile stain on church and state: Philip IV of France’s transparently self-interested libel, on Friday 13 October 1307, of the entire Templar order as sodomitical, idolatrous, Christ-denying, occultist heretics.

Two shocking facts become clear: that all Europe, including the Pope and the English king, knew the Templars to be wholly innocent but were either powerless or unwilling to intervene; and that the one man who did truly believe in their guilt, their tormentor Philip the Fair, was a paranoid maniac who later witch-hunted his own three daughters-in-law. The French royal lawyers condemned their victims on the murky testimony of ‘very reliable people’. Executive power hurling unsubstantiated denunciation seems a monstrously familiar image.

Comments