Although I stopped watching TV some years ago, films are a continuing solace and pleasure. Among the Christmas treats was a previously unseen Jack Nicholson movie, entitled The Bucket List. The plot revolves around two very different Americans, Nicholson and Morgan Freeman, both of whom are suffering from cancer and are given a mere matter of months to live. The Bucket List is their wish list of things to do before they die, some of the more exotic of which the wealthy Nicholson enables them to achieve. The excellent Freeman, a poorer man but the greater philosopher, reminds Nicholson of a more important consideration: the two questions asked of Ancient Egyptians at the gates of Paradise. Have you found joy in your life? And, has your life brought joy to others? The relevance of this self-interrogation is enacted during the remainder of the film’s narrative. It can also serve as a useful key to the current blockbuster exhibition at the British Museum.

I suspect that many of the visitors to the Book of the Dead show will emerge from its stygian gloom with little more understanding of Egyptian culture than when they entered. This is an immensely complex and utterly foreign subject, and I don’t think it can be easily elucidated by a display of papyrus fragments, mummy cases and grave goods, however much ‘state-of-the-art visualisation technology’ accompanies it. (In fact, the digital projections seemed pretty feeble and uninformative to me.)

This is an exhibition about the afterlife, about crossing the bar, and mankind’s urgent desire not simply to disappear at death. The Egyptians believed that the journey into the afterlife could be assisted by any number of objects and spells. The Book of the Dead is not a single book as we know it, but a collection of funerary texts and illustrated spells, embodying the magical power of word and image. We are in the territory of Harry Potter here, and no mistake.

Perhaps the extraordinary success of the Potter books and films helps to explain why this exhibition has now been mounted. There has always been a slightly ghoulish Hammer House of Horror attraction to Egyptian mummies at the BM, but a large paying exhibition about something as difficult to comprehend properly as the Book of the Dead? Certainly there were crowds of puzzled-looking people there when I visited — perhaps waiting to be enchanted.

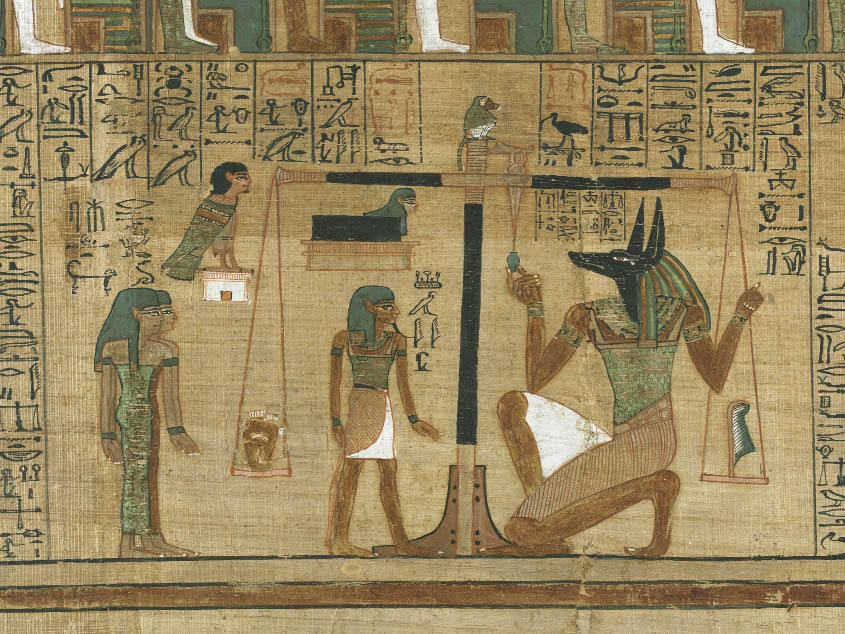

As the anecdote from The Bucket List illustrates, admittance to the Egyptian Paradise depended on how the individual had conducted his or her life. The tomb was the portal to the realm of the dead, and the Netherworld was a place of many dangers through which the dead had to travel before finding judgment in the presence of the god Osiris. Here the heart (as the site of intellect and memory) was weighed and the dead consigned to Paradise or to ‘the Devourer’, a monster who tidily consumed the damned. All this is supposedly made clear in the curving passages of this peculiar exhibition beneath the pale-blue enlightened ribs of Smirke’s great Reading Room dome.

The visitor is greeted by the golden mummy mask of Satdjehuty, fashioned in Thebes about 1500 BC. If you find this inscrutable, it may well set the tone for your response to the whole display, though there are many things of great beauty to be found. For instance, there’s a lovely slim serpent staff made of bronze from roughly the same period. This snake-wand was supposed to enable the bearer to take on the snake’s magic powers. (H. Potter, here we come.) Or there are intricately painted cedar-wood coffins, covered with spells. (There’s a handy incantation for repelling crocodiles.) A frieze of ink drawings of great delicacy contrasts rather savagely with a truly spooky group of black-varnished wooden statues of guardian deities. I much admired a blue-spotted bull and a satirical papyrus of animals playing a board game called Senet. And there are many passages of remarkable painting, in the Field of Reeds section, for instance. But I confess I was glad to exit the exhibition.

Upstairs in Room 90 is a free display of modern works on paper from the BM’s collection, entitled Picasso to Julie Mehretu. It opens with a marvellous gouache and watercolour study by Picasso for his radical early masterpiece ‘Les Demoiselles d’Avignon’. Treasure succeeds treasure. A couple of vibrant Kirchners in charcoal and coloured chalks contrast with a study by that great Canadian watercolourist David Milne, and a terrifying Otto Dix: ‘View of the Earth’, a grotesque mother giving birth to a starveling child in brush and ink, not unlike something out of the Book of the Dead, but less elegant.

The high quality of exhibits is maintained: really good things by de Chirico and Magritte, a Louise Bourgeois ink drawing from the late 1940s, two illustrations for Milton’s Comus by Charles Seliger (1926–2009), an artist previously unknown to me, also represented here by a lively 1945 biomorphic drawing in colour.

The unknown rub shoulders with the known, such as Matisse or Kiefer. There’s a cracking Bonnard watercolour of the dining room at Le Cannet (c.1940) and a frantically incised pen-and-ink drawing by Dubuffet. Abstraction is well covered: intriguing inventions by Hans Hofmann and David Smith, and a powerful brush drawing by Franz Kline.

Figuration is not neglected: a big triptych in coloured chalks from 1976 called ‘Sides’ by R.B. Kitaj shows what late-20th-century life drawing could be like. There’s a trio of Max Beckmann studies in a flat cabinet, two in pen, one in pencil, all three for ‘Fastnacht’ (1920). And in another case is a Visitors’ Book from the ICA donated by Roland Penrose because Picasso did a double-page drawing of ‘Leaping Bulls’, winged and brilliant in a corrida in the sky, as the first entry in it. An absolutely delightful show, far more absorbing than the death-obsessed Egyptians downstairs; just a shame there’s no catalogue.

Comments