‘Reading makes the world better. It is how humans merge. How minds connect… Reading is love in action.’ Those are the words of the bestselling author Matt Haig and though I wouldn’t put it quite like that, I too feel that there is something inherently good about reading. Daniel Kalder has no such illusions. His latest book Dictator Literature (published in the US as The Infernal Library) looks at the dark side of the written word.

It’s a study of what the great and not so great dictators of modern times read and wrote. In lesser hands this would be a romp (romp isn’t quite the right word, is it?) through Mein Kampf, Lenin’s What is to be Done? and Mao’s Little Red Book, but Kalder is nothing if not thorough. He’s read everything from Stalin’s lyric poetry to Saddam’s Hussein’s romantic fiction. He comes to the conclusion that the horrors of fascism, Nazism and communism would have been impossible without books.

The Bolsheviks in particular were steeped in literature: Lenin took the title of What is to be Done? from an 1863 novel by Nikolay Chernyshevsky. Karl Radek, a fellow communist, wrote that Lenin was ‘the first man who believed in what he wrote, not as something that would happen in 100 years but as a concrete thing’.

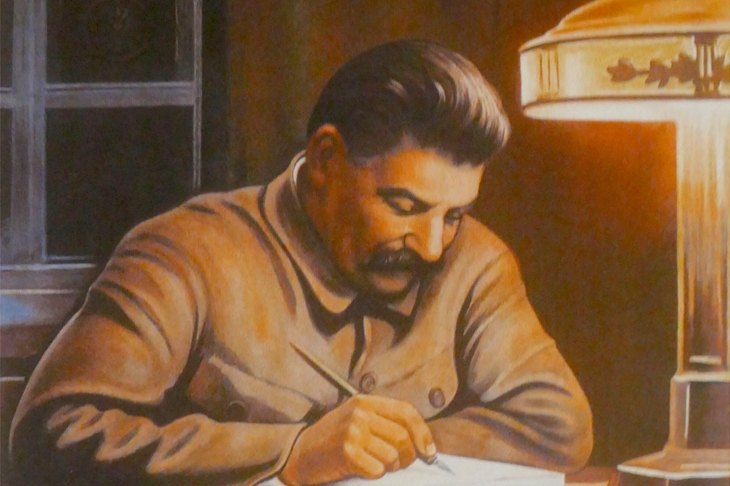

When Lenin died, Stalin not only took over Lenin’s corpse but his writing too. He became the editor, publisher and explainer of Lenin’s work — ‘like Saint Paul following in the footsteps of Jesus’ as Kalder puts it. In contrast to Lenin’s turgid prose, Stalin was ‘clear and succinct, and good at summarising complex ideas for a middlebrow audience’.

Stalin, brought up in poverty in Georgia, only learnt to read thanks to the church. As Kalder writes: ‘Teaching him to read was clearly an error of world-historical proportions.’ Putting the lie to the myth that literature has a moral power, Stalin loved reading and discussing the Russian greats. In Soviet Russia, however, culture would serve the revolution. The resulting work should stand as a lesson in how literature always suffers when writers get too cosy with power. Kalder writes of ‘Fyodor Gladkov, whose most famous novel was the thrillingly titled Cement, and Valentin Kataev whose most famous novel Time, Forward! was about pouring cement.’

All the Politburo wrote; success in dialectical theory was the key to rising in the party. At times the Bolsheviks seem like warring academics, only with much higher stakes: ‘The deployment of a bad review in ideological battles was a favourite tactic of Stalin.’

In contrast to Stalin’s prodigious output, Hitler was a lightweight. His ‘metier was talking rubbish, not scribbling it on paper’, as Kalder puts it. The destructive power of the book reached its apotheosis under Mao. The horrors of the Cultural Revolution were only possible in a literate society: 5,000 years of Chinese culture were replaced by one book, and China became in Kalder’s words a ‘vast stifling, ideological echo chamber’. After Mao, the rest of Dictator Literature can only be something of an anti-climax. Franco, for example, was ‘content to bore his local readership exclusively, while leaving the rest of the world alone’.

With a few exceptions — Mussolini wrote vividly about his experiences in the first world war — these dictators were spectacularly bad writers. You might think therefore, that this book would have its longueurs, but Kalder has a gift for engagement. He is very funny, at times almost Jamesian (Clive that is): Castro is the ‘pontiff of pontification’ and Stalin ‘the Bill Bryson of dialectical materialism’.

Millions of copies of Stalin’s works were printed, but few survive. They ‘went the way of the books of so many bestselling authors whose success tapers off after their deaths’. Mein Kampf, however, remains baffling popular, especially in the Arab world, and the writings of the Ayatollah Khomeini have proved terrifyingly influential; we are no longer surprised when Islamic blasphemy laws are routinely followed in secular societies

The spirit of dictator literature is now all around us: in opaque critical theory, in judging culture by political standards and the show trials of social media. After reading Dictator Literature you will never look at books with such a benevolent eye again.

Comments